As Bloomberg’s Richard Breslow details in today’s note, the worst kept secret in the financial world is now not only accepted orthodoxy, but finally being discussed openly by, at least some, authorities.

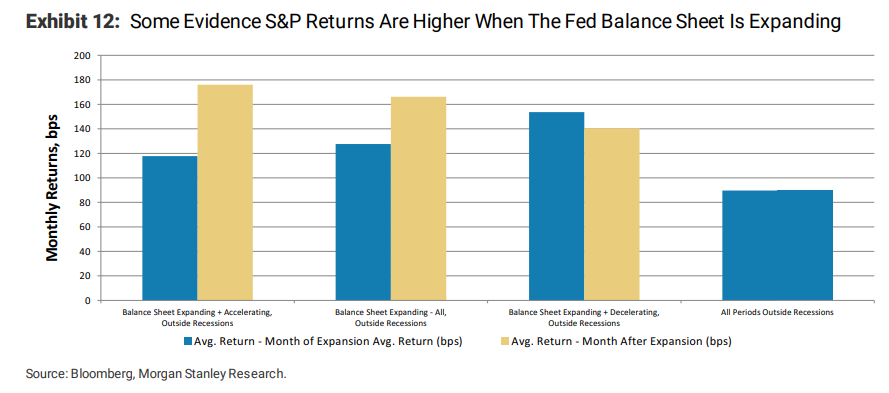

Central bank policies are directly driving asset prices and the bubbles therein. It’s what they do. It has been so stunningly obvious that, at this point, it makes a mockery of things to deny it as an ongoing, and essential, part of how their strategy is implemented. Oddly enough, however, it’s a revelation that is, apparently, coming late to many people with a lot of savings and nothing to show for it. And it is an undeniable factor in this January’s price action.

- Alan Greenspan knew it to be the case.

- Ben Bernanke had no problem with it. His strategy required it.

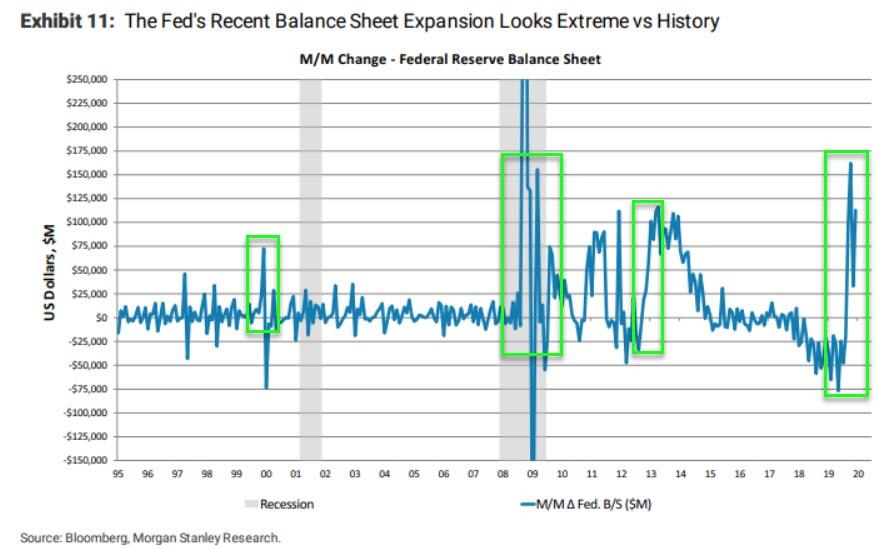

- Jerome Powell, was probably initially not enamored about it but saw no way around it. It fell on ardent loyalists to take his insistence that it was “not QE” with any seriousness. Otherwise, they would have had to admit to knowing little about financial markets.

In some ways it was refreshing that Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan openly talked about it in an interview Wednesday. Although he did couch it in terms that implied it was a matter of some concern to him. But, of course, he went on to say, “we’ve done what what we need to do up until now.”

“My own view is it’s having some effect on risk assets,” Kaplan said.

“It’s a derivative of QE when we buy bills and we inject more liquidity; it affects risk assets. This is why I say growth in the balance sheet is not free. There is a cost to it.”

He doth protest, just not so much. Their ability to drive investor behavior is so well established that what is going on in the markets can’t remotely be seen as an unintended, or even unwanted, consequence.

At this point, is it a bad thing to admit something that is so patently evident to everyone?

The answer is probably yes.

They have always been responsive to financial conditions. In many ways they’ve been transfixed by them. Now they are openly acknowledging that they own them. And once you do so, it becomes harder than ever, if even at all possible, to give them back. Kaplan said they need to “come up with a plan and communicate a plan for winding this (balance sheet) down.”

That would be nice. And good luck with that.

At this point, you have to wonder if it even matters whether it is true or not. We are back in the mode of just wanting to find something to buy. Stocks act as if they are bullet-proof. Stock buy-backs look like they are front-running the inevitable rather than being the cause of it. Reports of new all-time highs, need to include the word “again.”

Calls to exercise caution by limiting duration are once again being dismissed as just leaving yield on the table. Italy sold 30-year debt this week. A 7 billion euro offering saw bids of some 45 billion euros. And this hasn’t been an isolated case. Other European countries have been enjoying the opportunity. Bond issues from Japan and Australia flew off the shelves earlier this week. Five-year JGB yields at negative 9.5- basis points were seen as oozing value.

We, quite properly, worry that central banks are running low on ammunition to fight any future recession. This translates into what looks like a “risk-on” environment. But it is just the opposite. Yield remains the primary game in town. With an expectation that it will be in dwindling supply.

This is not to say that investors are at all acting irrationally. And central banks feel they have no choice in the absence of broader policy prescriptions. It’s merely an attempt to describe what we all see. Most worryingly, I keep hearing from people who are sure that it’s obvious where we go from here.