Merrill Lynch har analyseret de største recessioner de seneste 100 år og kommer til det resultat, at coronakrisen – økonomisk – kan ende hurtigere, end mange venter. Mange er grebet af panik, men hvis politikerne og centralbankerne griber rigtigt ind, kan krisen ende hurtigere end finanskrisen og depressionen, nemlig som krisen efter markedskrakket i 1987 endte. Det skyldes, at coronakrisen skyldes et pludseligt opstået problem, og at der ikke er en bagvedliggende svækkelse af økonomien. Denne krise er anderledes. Vi synes at have lært noget, skriver Merrill.

Uddrag fra Merrill:

MACRO STRATEGY

What’s Different This Time

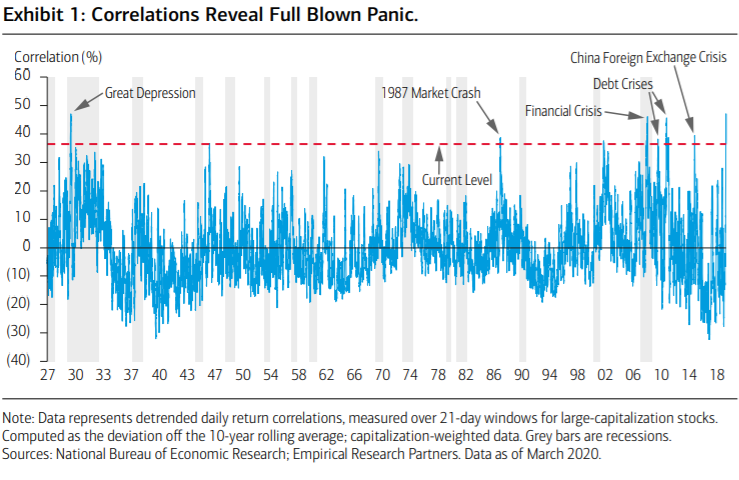

The unprecedented coronavirus panic and economic shutdown have precipitated extreme

financial-market reactions only seen in previous crises such as in 2008–2009 and

1929–1933. For example, return correlations of large-capitalization stocks (Exhibit 1)

as measured by analysts at Empirical Research Partners rose to levels a bit above those

seen in the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008–2009 and only matched by those

observed at the beginning of the Great Depression. In short, the coronavirus selloff

compares with the other two greatest financial panics of the past 100 years. When

correlations are so high, it means there’s indiscriminate selling of everything—good and

bad—as in “throwing out the baby with the bathwater.”

Inevitably, the enormity of what has happened in financial markets has prompted

comparisons with the aftermath of the Great Depression collapse. This has led some

prominent money managers and strategists to warn that “a prolonged period of hard

times and new lows in equity prices is ahead.” This is possible, but not necessarily

inevitable. The outcomes ahead will depend on the particular circumstances of our

current problems and, importantly, on how policymakers respond to them. When we

assess both the nature of the problem and the mitigation policies being applied,

we conclude that the coronavirus bear market will eventually turn out to be more

comparable to the 1987 bear market than that of the Great Depression.

The S&P 500 peaked at about 336 on August 25, 1987, and was relatively flat until early

October, when it began to fall and then collapsed on October 19, 1987, in the biggest

one-day percentage drop ever seen. Almost all the 33% decline occurred between

October 5 and October 19. Similarly, the S&P 500 recently peaked just shy of 3,400 in

the third week of February 2020 and fell to a low near 2,200 on March 23 for a decline

also of about 33%. Both declines were unusually fast, and, as shown in Exhibit 1, the high

correlation observed in 1987 also almost matches the correlation observed in the current

bear market, a key metric of widespread panic.

Most economists predicted a recession would occur after the 1987 drop in equity

prices. Instead, a quick policy response and a strong underlying economy defied their

predictions and the secular bull market resumed, although it took the better part of the

next two years to set a fresh S&P 500 record high.

The 1987 experience was unusual in a couple of respects. First, most bear markets are

preludes to recessions. However, the 1987 drop, especially its speed, was caused by

new financial technology, in particular the use of “portfolio insurance,” which the Brady

Commission investigation of the crash primarily blamed for the unprecedented nature of

the October 19 collapse.

The 2020 stock-market collapse is similarly the result of a one-off factor rather than

reflecting a buildup of pre-recession weaknesses. The U.S. economy was strong when

the government response to the pandemic brought it to its knees. Indeed, the Atlanta

Fed’s GDPNow estimate for the first quarter was tracking around 3% up until the

middle of March. As in 1987, there was a specific, exogenous cause for the extremity

of the selloff. Moreover, the cause is clearly identifiable, and the conditions to stop its

negative impact are well understood: flatten and turn the case curve down and prevent a

recurrence through social distancing, testing, therapeutics and, eventually, a vaccine.

There is growing confidence about the timeline for cases in more countries, and

schedules for reopening are starting to emerge. As timeline uncertainty recedes, policies

to tide over household and small-business incomes have already been tailored to address

the labor-income and business-revenue shortfalls, essentially extending a bridge to the

other side. Without this bridge, defaults and bankruptcies would likely rise to systemic

levels, causing the kind of scenario that created the Great Depression.

Those looking for a Great-Depression scenario this time around are essentially predicting

that these policies will fail to prevent a proliferation of defaults and an extended

recession or even depression. These concerns are evident in the relative performance of

the equities of companies perceived to have higher bankruptcy risk. Empirical Research

analysts find that so far this year the relative returns of companies with high and low

bankruptcy risk showed the biggest differential in performance compared to any year

since 1965.

The answer to the question of whether there will be a lower low and an extended

recession largely depends on the effectiveness of policies to bridge the financing

gap over the shutdown period and allow the economy to reopen in a still favorable

environment for renewed growth.

Interestingly, in the Blue Chip Survey of Economic

Forecasters, 87% of economists responded right before the passage of the Coronavirus

Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (“CARES Act”) that they were doubtful that these

policies would be effective. Yet, when we analyze the policy response, it is clear that

it has benefited from the lessons learned both from the Great Depression and the

GFC. Indeed, it’s fair to say that the GFC, bad as it was, was not as bad as the Great

Depression, precisely because of the lessons learned from that traumatic experience.

Similarly, we doubt that the current recession will be as bad as the GFC, precisely

because of the lessons learned from that experience.

The GFC unfolded in stages over more than a year, as did the policy response. The collapse

of Lehman Brothers was the catalyst for the deepest phase of the crisis, and it occurred

nine months into the recession. The coronavirus pandemic effect manifested in just two

months. In record time, the biggest ever financial response was also set in motion to

bridge the shutdown period.

A second response is likely soon as the shortcomings of the

first response and the need for extended benefits become apparent. This is designed,

and will be bolstered as needed, to preclude the wave of bankruptcies and defaults that

would create the bearish outcome some expect. Unlike the fiscal response to the GFC, this

intervention is not spread out over a decade. It is bigger, quicker, and designed to directly

help the specific parts of the economy that are the source of the problem.

Finally, the Fed learned from the Great Depression and then learned more from the GFC.

As a result, it had emergency response programs on the shelf and brought them out

immediately for this crisis. The specifics of the current crisis mean that problems were

more concentrated outside of the banking sector compared to the GFC. The Fed, together

with a strong banking sector, makes it possible to address the problems, and the results

are encouraging. Pro-growth economic policies in place prior to the onset of the pandemic

are also a positive for a quick return to growth compared to the post-GFC period.

This crisis will also provide lessons for dealing with the next crisis. Importantly, fiscal

policy can be more directly and efficiently applied using the private financial system to

get money directly to people instead of looking for shovel-ready projects. Businesses can

use direct support to maintain operations instead of creating government make-work

projects and bridges to nowhere.

These differences between prior crises and the current one suggest those waiting for

the other shoe to drop may be “waiting for Godot.” If the money in the CARES Act gets

distributed over the next few weeks and the economy begins to reopen as the pandemic

gets under control, the train will “leave the station” and the coronavirus bear market will

turn out to be just a pause in a secular bull market, just as the 1987 crash proved to be.