Natixis ser nærmere på værdikæden, som er kommet i centrum under pandemien. Der er ikke kun politiske grunde til at se på betydningen af værdikæden og globaliseringen. For virksomhederne kan der være økonomiske grunde til at gøre sig mindre afhængig af den mest effektive værdikæde, når et enkelt led kan bryde sammen og skabe problemer. Derfor kan det være klogt at have en mere løs værdikæde, selv om den på kort sigt kan fordyre produktionen, mener Natixis.

TRADING PACES-HOW IS TRADE EVOLVING: FROM TIGHT COUPLING TO LOOSE COUPLING

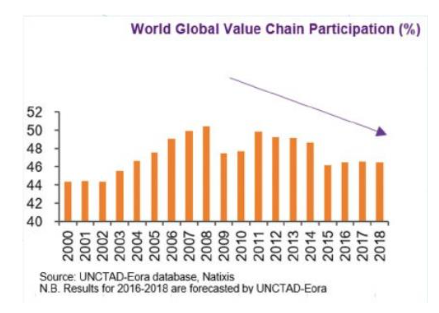

Trade has been bumpy over the last 15 years. There was a massive collapse during the global financial crisis, followed by a rapid recovery and collapse in 2015 as a consequence of falling oil prices and China’s economic woes. COVID-19 has been the third major shock to global trade in only 15 years, and possibly the most important. COVID-19 is a different kind of shock to the other two, as it brings into question the way in which a substantial amount of trading has been organized over the last few decades.

This is due to the massive increase in the efficiency of ports, especially in China, especially thanks to the introduction of containerization. In fact, value chains – loosely defined as the cross-border movement of the parts and components used in production to reduce cost from increased specialization –are a result of globalization, and they explain the massive increase in trade flows.

Effects of the trade war

This process was facilitated in the past few decades by substantial reductions in trade tariffs, as well lower transportation and communication costs. However, these tailwinds have been fading at an accelerated pace since 2008. Trump’s trade war against China created new challenges to global supply chains, which had become increasingly China-centric over the years.

As if this were not enough, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in January 2020 created big disruptions in the supply chains, and led to shortages of parts and components for manufactured products, especially autos and ITC. On top of that, shortages in medical appliances, including those most needed to combat COVID-19, has further added to the impression that global value chains are not resilient enough to shocks.

The gravity of the pandemic has clearly added a political, and nationalistic, aspect to the debate about the need to reshuffle global value chains. But we should not forget that there are also economic reasons for such a move. In fact, one can think of value chains having been built in the past to maximize efficiency and, thus, increase corporate profit.

In other words, a “tight coupling” model has so far been used to build supply chains in as far as a single-entry point has been offered to each of the steps in a supply chain. That means if one of the entry points fails, the whole chain breaks down.

Environmental shocks, the US-China trade war, and the current pandemic has pushed companies to think about changing their operations from “tight coupling” to “loose coupling”.

In other words, instead of a single point of entry for each step of a supply chain, companies prefer to have several interchangeable options. This, of course, increases the cost of production in the short run, but it increases resilience. Higher resilience might also imply lower costs in the long run, depending on whether major shocks can be avoided. Accordingly, the capacity to keep the production process intact, even when a component is temporarily affected by a disruption in production, has become an increasingly important objective for companies.