USA står over for en ny periode med relativt høj vækst, god indtjening hos lønmodtagerne og høj indtjening hos virksomhederne, skriver Merrill. Det viser en kraftig stigning i pengeforsyningen. Økonomien under pandemien udviklede sig helt anderledes, end alle forventede. Der blev den korteste nedtur nogen sinde under en recession, og de enorme stimulipakker skabte langt større værdistigninger og vækst hos virksomhederne samt en større inflation, end nogen havde ventet. Virksomhedernes overskud i 2021 blev på godt 23 pct. Økonomer og centralbanken tog fejl af udviklingen som sjældent set. Mens væksten i USA i de seneste par årtier har ligget under 4 pct., kommer den over dette niveau til 6-7 pct. fra og med 2022 – trods en højere inflation og stigende renter.

A New Dawn for Nominal Growth

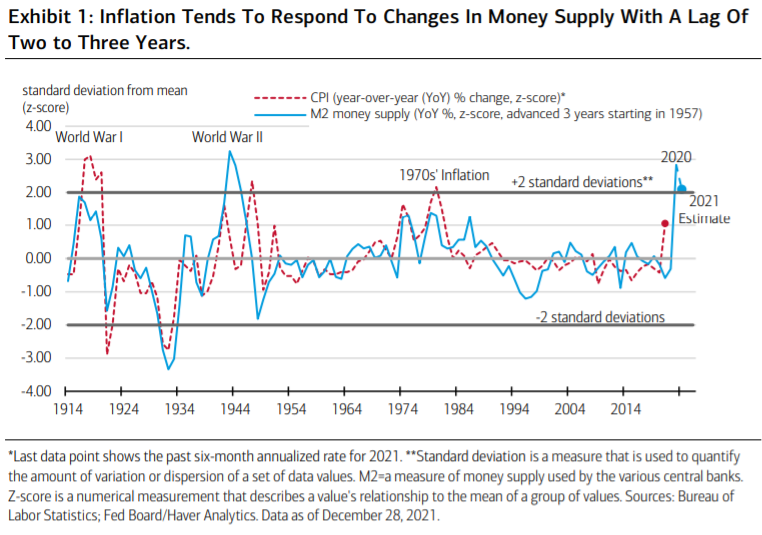

After two decades of sub-4% nominal GDP growth, inflation below 2%, and fears of

endless stagnation, the U.S. economy took off in 2021. The reason is simple. As shown in

Exhibit 1, after the inflationary money growth of the 1960s and 1970s, then Fed Chair

Paul Volcker reined in money growth, and it grew well below its historical average for three

decades until the pandemic.

As a result, inflation fell, reaching just-below 2% during the

“secular stagnation” era between 2009 and 2019.

As shown in Exhibit 1, the biggest monetary surge since WWII has broken the back of

secular stagnation. The world economy has gone from chronic excess supply to chronic

excess demand in less than a year. The supply shortages still baffling analysts are simply

the result of too much demand relative to the capacity of current supply chains.

For the markets, the main implication of this new era is that nominal

growth will likely settle back into a more normal historical range of 6% to 7% after the

unusually low nominal growth (3% to 4%), inflation and interest rates of the pre-pandemic

secular stagnation era.

The dawn of this new era has caught the Fed and consensus economists by surprise.

According to the consensus forecast in the Blue Chip Economic Indicators for January

2021, consumer prices were forecast to rise just 2% in 2021. The Fed maintained that the higher inflation that was actually observed in 2021 was “transitory” even as it averaged

above 7% by year end, marking the biggest forecast error by economists in at least 40

years. A simple look at Exhibit 1 a year ago would have suggested the high-single-digit

inflation surge that actually occurred.

It’s not just inflation forecasts that were wide of the mark. Economists also

underestimated real GDP growth, nominal GDP growth, industrial production, personal

income, consumer spending, business fixed investment and, particularly, corporate profits.

For example, in January 2021, they forecast that profits would grow 8.1% in 2021. By

December, with three quarters of huge positive surprises, profits growth was tagged just

above 23%. These enormous profits surprises have driven the powerful Equity bull market

in 2021.

These huge misses are the result of the unprecedented stimulus and its underestimated

effect on nominal GDP, which is what governs business and consumer incomes, sales and

investment, profits and production. Over the course of 2021, the consensus forecast for

nominal GDP growth rose from 6% to almost 10%.

Ever since the first Coronavirus Aid,

Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) was passed in March 2020, economists

have failed to properly gauge the effect of policy stimulus on the economy, focusing

instead on the downside risks from coronavirus. However, the first CARES Act already

plugged the economic hole from the shutdowns, causing incomes to rise for the first time

ever in a recession that was also the shortest in history.

We expect this cyclical outperformance to continue since the Fed remains highly

accommodative according to its own projections. One of the best leading indicators of the

business cycle is the yield-curve spread between the fed funds rate and the 10-year

Treasury note.

That spread widened significantly in 2021 as the Fed funds rate stayed

near zero and the 10-year yield rose about 50 basis points. A steeper yield curve is a sign

that policy is getting easier, not tighter. Also showing that policy remains highly

accommodative despite faster tapering and rate-hike expectations, real rates remain

deeply negative across all Treasury maturities. Credit spreads also remain unusually narrow

by historical standards, consistent with healthy profits and relatively easy financial

conditions.

Eventually, over the course of 2022, these indicators will reflect tightening

financial conditions and weaker economic growth but not until the Fed gets ahead of the

curve.

However, the pandemic caused the Fed to shift from a preemptive policy of “skating

toward where it expected the inflation puck to be in the future” to a reactive policy of

waiting until it saw the whites of inflation’s eyes.

Being behind the curve means the Fed is

skating toward where the inflation puck was. In the 1970s, a similarly flawed reactive

policy caused the Fed to sustain excessive money growth and inflation, much as it did in

2021.

Right now, the composite index of leading indicators is up about 10% from a year

ago, a very strong signal that the U.S. economy is entering 2022 with a full head of steam

even as inflation is way ahead of expectations. This suggests strong incomes, spending,

revenues and profits will continue well into 2022.