Hvad er Urban Mining? Hvad er E-Waste? Det er to nye begreber, som Merrill beskriver i en analyse af et helt nyt investormarked – nemlig det marked, der består af genindvinding af værdifuldt affald som forældede mobiltelefoner, computere, ledninger, batterier, tv-skærme osv. Det er spildprodukter, der vokser i værdi, især med digitaliseringen og øget hjemmearbejde. Det årlige spild svarer til 350 milliarder kr. pr. år, og det svarer til et lille lands bruttonationalprodukt. Kun 17 pct. genindvindes. Europæerne er langt bedre til genindvinding end amerikanerne og asiaterne. Genindvinding ventes at tage til, fordi den unge generation er blevet mere miljøbevidst – og så er det ganske enkelt blevet en god forretning og derfor et investor-emne, skriver Merrill.

The Coming Boom in “Urban Mining”

“Cities are the mines of the future.” ― Jane Jacobs, Visionary Urbanist

“Urban mining” sounds like an oxymoron because when investors think “mining,” they think of

massive, dusty machinery gouging out a parcel of land in a sparse part of a distant country in

search of a valuable commodity—whether it be iron, gold, copper, silver, palladium or other

minerals and metals.

That’s traditional mining, which is booming of late due to a number of

factors, ranging from stronger-than-expected global growth to the metal/mineral-intensity

of the Green Revolution.

Then there is “urban mining”—a term largely unfamiliar to investors but one that will

become commonplace in the years ahead. This type of mining can take place anywhere (with

resource-deficient Japan an emerging leader) and pivots on mining, recycling or recovering

raw materials from e-waste largely found in cities.

What’s e-waste? Think discarded devices

like mobile phones, PCs, televisions, batteries, household appliances, printers, and related

electronic items like monitors and cords.

E-waste is a residual of a more prosperous world in general and a world increasingly gone

digital in particular. Overlay the pandemic and attendant surge in remote working, and the

supply of e-waste has only soared over the past few years. To this point, with work and

education more home-based, global personal computer sales (and other hardware

accessories) have soared since 2020.

Also adding to the e-waste mountain: shortened

product lifecycles, the global diffusion of the internet and therefore an expanding hardware

user base, and the digitalization of one industry after another.

The soaring costs of traditional raw materials are also driving interest in urban mining, as is

the fact that it’s become more cost efficient (and therefore profitable) to mine an iPhone,

computer or monitor as opposed to leaving pox marks all over the global landscape.

Speaking of pox marks, urban mining also scores well with environmental, social and

governance (ESG) factors, since it leaves a smaller environmental footprint relative to

traditional mining, which requires an abundance of energy, sand and water, and produces

harmful climate residuals.

Some key numbers to consider:

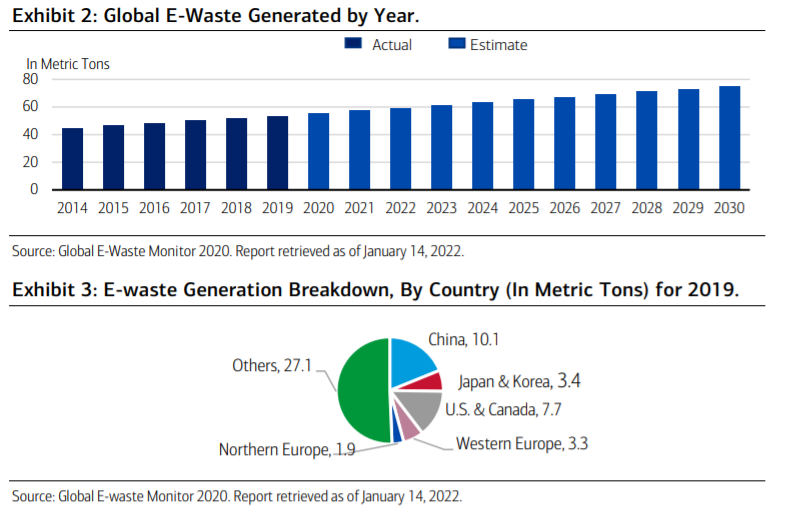

According to the World Bank, the world generated a record 53.6 metric tons of e-waste in

2019, the last year of available statistics, versus 9.2 metric tons in 2014. The World Bank

estimates that e-waste will grow to around 75 metric tons by 2030, a doubling in roughly 16

years1 (Exhibit 2).

• The value of raw materials in the global e-waste generated in 2019 totaled roughly $57 billion,

more than the GDP of many nations, with iron, copper, and gold contributing the most in value.

Up to 7% of the world’s gold may currently be contained in e-waste.1

• Asia accounted for nearly half (46.5%) of total e-waste in 2019, followed by the Americas

(24.4%) and Europe (22.4%)1

. By country, China was the largest producer of e-waste in

2019 (Exhibit 3).

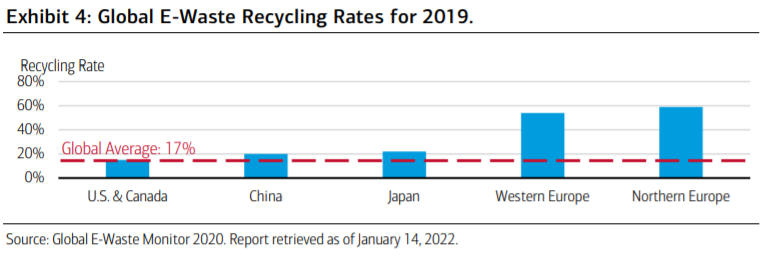

• Only 17.4% of e-waste was collected and recycled in 2019, i.e., mined. That means a

staggering sum—some 44.3 metric tons of e-waste—was discarded, incinerated or illegally

exported to lower-income nations for second-hand production1 (Exhibit 4).

• Electronic waste represents around 2% of waste in U.S. landfills but accounts for

roughly 70% of total toxic waste, and hence the urgency to recycle/mine e-waste.3

• One iPhone requires 46 different elements,4 with gold, palladium and platinum among

the top three.

All of the above is another way of saying that there is tremendous upside potential for

urban mining—notably in a world where resource scarcity, extraction and emissions are

intensifying.

It’s unlikely that the past will be prologue. More nations are awakening to the hazards and

opportunities associated with e-waste and have stepped up the pace of legislation

encouraging recycling and related activities. More corporations are designing more

products that can be reused and recycled, and leveraging technology to harvest secondhand products and components. Consumers, meanwhile, notably millennials and Gen Z, are

increasingly aware of their digital footprint and increasingly demanding that firms and

governments adopt more sustainable products and policies.

All in all, we are in the early innings of the creation of the circular economy, where the

model of “recovery, reuse, remanufacturing” eclipses the “take-make-dispose” model of the

past. Urban mining is a key node in this new model and is set to ramp up significantly in

the years ahead.