Krigen i Ukraine og det nye covid-udbrud i Shanghai griber afgørende ind i den globale handel og produktion. Det globale PMI faldt med 0,7 point til 53 point i marts. De barske indgreb mod covid-udbruddet i Kina kan føre til, at den kinesiske vækst falder til 5 pct. i år mod hidtil ventet 5,5 pct. Men generelt vil flaskehalsproblemerne stige i de kommende måneder, og der vil først ske en lempelse, når covid-udbruddet i Kina bliver slået ned, vurderer ABN Amro.

Ukraine war and China lockdowns hit manufacturing, add to bottlenecks

Global Macro: Ukraine war hits global manufacturing, adds to cost push inflation. Wider lockdowns in China another headwind, adding to global supply bottlenecks.

Global Macro: Ukraine war hits global manufacturing, adds to cost push inflation

After having picked up in February, the global manufacturing PMI dropped by 0.7 point to 53.0 in March, the weakest reading since September 2020. This decline was broad-based, with particularly the global PMI subindices for future output, domestic orders and export orders losing ground.

Two key factors are driving this slowdown. In the first place, the war in Ukraine – starting late February – has driven significant drops of the manufacturing indices in March in several regions/countries: among the developed economies, particularly the UK and the eurozone are hit.

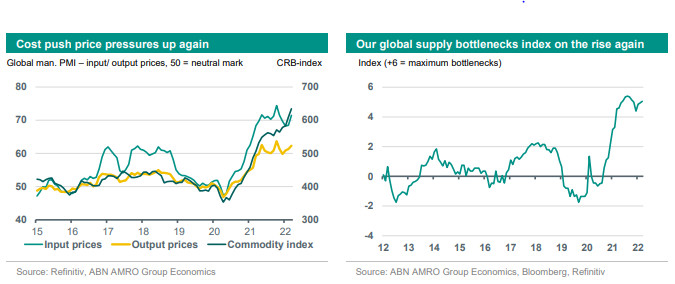

This is offset by improving indices in the US (Markit) and Japan; as a result, the aggregate index for developed economies was more or less stable in March. That said, the distress that this conflict has created on commodity markets (energy, food, metals) has contributed to a renewed rise in the cost price subindices. The global PMI sub-index for input prices rose by 3 points to a four-month high of 71.5, and the sub-index for output prices by 1 point to a five-month high of 62.3.

Wider lockdowns in China another headwind …

Another key factor driving the slowdown in global manufacturing is the widening of lockdowns in China, as the authorities maintain strict covid-19 policies amidst the spread of Omicron. As a result, China’s manufacturing PMIs – both from Caixin and NBS – fell below the neutral 50 mark again in March, driving a significant drop in the aggregate index for emerging economies by 1.7 point (to 49.2).

Obviously, China’s services PMIs were harder much harder, with Caixin’s services PMI coming in at 42.0 earlier today – the lowest level since the initial covid-19 shock in February 2020. With lockdowns in large cities such as Shanghai continuing, we expect these drags to remain visible in April, and perhaps even longer. The Chinese leadership has repeatedly stressed the need for vigilance on the pandemic front in the run-up to important political events later this year, even though public acceptance for these policies seems to wane.

Although we expect ongoing targeted policy support to partially offset this, we had already reduced our near-term growth forecasts for China, and had cut our annual growth forecast for 2022 to 5.0% (below Beijing’s growth of 5.5% – also see our recent publication here).

… adding to global supply bottlenecks.

In line with our expectations, the spread of Omicron and the widening of lockdowns in China also causes a delay in the easing of global supply bottlenecks and the normalisation of supply-demand imbalances.

After easing in late 2021, our global supply bottlenecks indicator has risen again over the past few months, indicating increasing bottlenecks. The recent increase of this index is mainly driven by the pandemic-related disturbances in China (component ‘output EMs/orders DMs’).

That said, some of the indicators point to an easing of these bottlenecks. Global container tariffs have fallen to a 9-month low in March, and the Baltic Dry index is clearly below the post-GFC peak reached in September 2021. Moreover, with the orders’ components under pressure due to the Ukraine war, supply-demand imbalances could start easing again, particularly when pandemic disturbances in China fade.

That said, this index should be seen as a global macro index for supply-demand conditions; it does not include variables related to domestic issues such as congestion in specific ports, or labour supply. Nor does it capture variables related to the scarcity or even distress in commodity markets, which can be volatile and idiosyncratic in their drivers as the Ukraine war has once more illustrated.