ØU Kommentar: Producentpriserne falder nu meget hurtigere end forbrugerpriserne, og det stigende gab varsler øgede overskud i virksomhederne. Det er godt for aktierne.

Uddrag fra Authers:

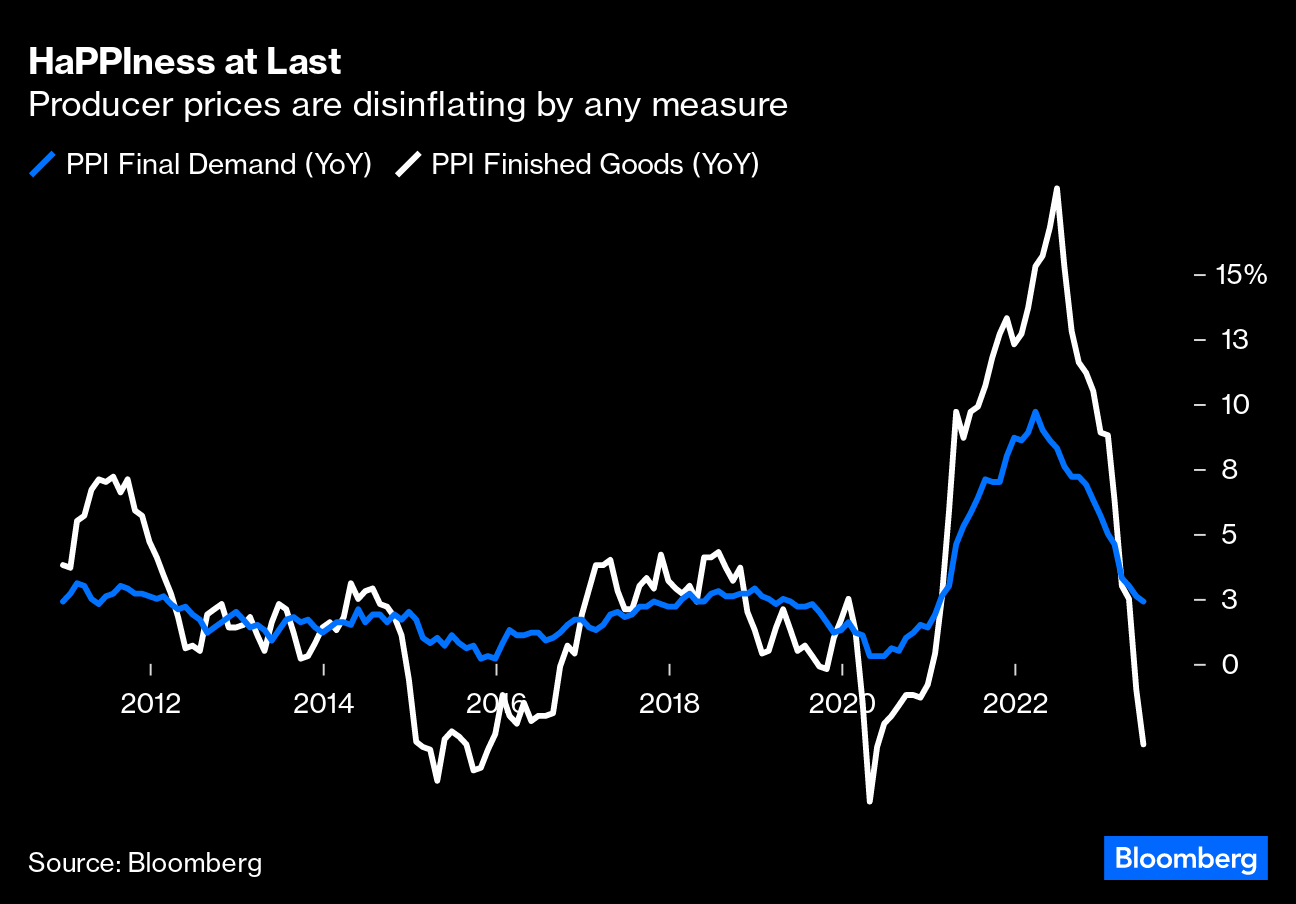

More great news for those who hate inflation. The day after the US Consumer Price Index came in below expectations, producer prices performed the same trick. Indeed, if measured by the traditional method of tracking finished goods, PPI in the US has gone negative:

The battle against inflation is now plainly being won. Victory isn’t inevitable, and its timing remains uncertain, but the scenarios of “stagflation” or even “hyperinflation,” as some have discussed, look much, much less likely now. Meanwhile, the way that the PPI is lagging the CPI is truly extraordinary. It suggests the economy is in a different place from where more or less everyone thinks it is, as Bespoke Investment points out:

Whether we look at PPI Final Demand or PPI of Finished Goods, the spread between consumer prices (CPI) and producer prices (PPI) is at a record high. Prior periods where the spread hit a record high were typically followed by above-average equity returns and occurred very late in a recession or in the early stages of an expansion.

Emphasis is from Points of Return. It makes sense that a big drop in the supply costs will help equities. It’s bizarre that this is happening, when the economy is plainly neither late in a recession nor in the early stages of an expansion. So how to explain this?

Maybe, that the economy isn’t destined for recession at all, despite all the usually reliable indicators saying that it is. Goldman Sachs has now puts its odds on a downturn within the next 12 months at only 25%, and says activity has risen this year at a rate consistent with the economy growing faster than potential. John Vail of Nikko Securities expressed the arguments as follows:

Economists have often predicted recessions that did not happen, so it’s not a huge surprise. In the first half, US consumers, especially wealthier ones who actually benefit from higher interest rates, have kept up their spending, partly due to accumulated savings and pandemic stimulus packages. Also, house prices did not fall much and thus there was not much of a negative wealth effect from that. Finally, the decline in gasoline prices helped confidence, there is much pent-up demand for automobiles after previous production shortfalls, and strong demand for travel and entertainment too.

Not only can all of this happen, it appears, but it can do so without pushing inflation upward again — the so-called “immaculate disinflation.” This is where some of the more optimistic scenarios get a little harder to believe. So, time to look more closely at what the market is saying.

Market Signals |

Last week, as Points of Return reported, there was a breakout in yields, with two-year bonds yielding more than 5%. This doesn’t happen often, and is often followed by a sharp reversal, which is exactly what’s happened this time. The level of 5.07%, at which the yield peaked both last week and in early March before the regional banks crisis, seems like an invisible barrier. But while the behavior of the bond market has been identical in both months, expectations for the Federal Reserve haven’t been. At all. The blue line in the following chart shows the implicit fed funds rate predicted for the December meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee. It tanked even more than bond yields back in March, and it’s barely moved recently:

The explanation lies in the banking crisis. In March, the supposition was that the Fed had already tightened so much as to break something, and that rates would have to fall imminently. This time, the supposition is that the Fed will stay on hold for a while. Bond yields are falling because of the suspicion that the Fed will stay too tight for too long, and ultimately damage the economy. That’s a reasonable fear at this point, and should at least temper some optimism.