By Vishwanath Tirupattur, global head of Quantitative Research at Morgan Stanley

Credit’s Low-Beta Opportunity

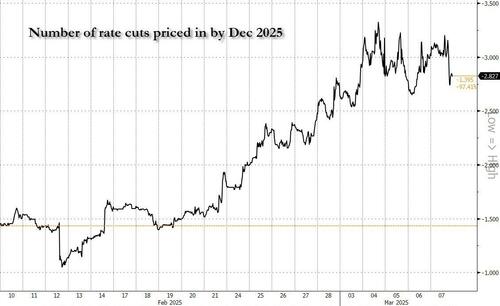

Market sentiment has shifted quickly from post-election euphoria and animal spirits to increasingly serious concern about downside risks, driven by ongoing policy uncertainty and a spate of uninspiring ‘soft’ data. The macro markets now expect the Fed to pivot from fretting about inflation to worrying about growth. Market pricing of rate cuts in 2025 has swung from about one cut a few weeks ago to three cuts Friday.

The pricing of the terminal rate has also moved notably lower, with its arrival much sooner. After reaching an all-time high just a few weeks ago, the S&P 500 has given up all its gains since the election and then some, in line with our US equity strategy team’s outlook for a tougher first half and a 5,500-6,100 trading range due to slower growth. Treasury yields have also yo-yoed, from a 40bp sell-off to a 60bp+ rally. Yet amid this volatility in equities and rates, credit markets have barely budged, resonating with our constructive credit view. While the credit market’s resilience has strong underpinnings, potential challenges to its ‘low beta’ are worth considering.

Our constructive stance on credit through 1H25 assumed that many of the supportive factors from 2024 would continue – solid credit fundamentals and strong investor demand driven by elevated overall yields rather than the level of spreads (with the refrain ‘spreads are tight, but yields are right’). We expected economic growth to slow somewhat, to around 2%, still a robust level for credit investors. These expectations have largely played out until recently. Credit fundamentals and market technicals have remained strong, arguably well above average, with supply from new issuance remaining manageable. While we maintain our overall positive stance on credit, some of the factors contributing to its resilience are changing, calling the persistence of credit’s low beta into question.

We have argued that the sequencing and severity of policy would be key drivers of the economy and markets in 2025 (see here and here for example). While we did expect growth-constraining policies (tariffs and immigration controls) to precede growth-supportive initiatives (tax cuts and deregulation), their severity has been greater than we anticipated. This is especially the case with tariffs, which have come in faster and broader than we had penciled in. Our US economists’ outlook assumed a slower ramp-up of tariffs on China and did not include tariffs on Mexico and Canada. While Mexico and Canada tariffs may be short-lived, reciprocal tariffs across US trading partners are now part of our economists’ baseline. Furthermore, announced public sector layoffs are deeper than we anticipated, while border crossings have slowed sharply.

Incorporating these signals, our US economists led by Michael Gapen have pulled forward the anticipated effects of restrictive trade and immigration policies by marking down real GDP growth to 1.5% in 2025 (4Q/4Q) and 1.2% in 2026. They now expect the greater intensity of tariffs and a still-tight labor market to result in inflation, with headline and core PCE inflation at 2.5% and 2.7%, respectively, in December 2025, up from 2.3% and 2.5% previously.

From a credit perspective, we would highlight that our economists are not calling for a recession. Their growth expectations still leave us in territory that we would deem credit friendly, although edging towards the bottom of our comfort zone. Cooling growth may also temper animal spirits and continue to constrain corporate debt supply, keeping market technicals supportive as they have been in the last few months. Fund flows into credit have been very strong, and while Treasury yields have rallied, overall yields are still at levels that sustain demand from yield-motivated buyers.

That said, if growth concerns intensify from these levels, with weakness in ‘soft’ data spreading notably to ‘hard’ data, the probability of markets assigning above-average recession probabilities rises. This could challenge credit’s low beta, and credit beta could increase on further drawdowns in risk assets.

That credit spreads have not budged much provides an opportunity to position for the risk of incremental deterioration in incoming data through liquid credit hedges. As Vishwas Patkar, our head of US credit strategy, highlights, hedging remains quite cheap, especially via credit derivatives and macro products. He notes that CDX spreads screen very tight relative to cash and equity volatility and recommends CDX hedges, both in index shorts and out-of-the-money puts.