Uddrag fra Authers/ Bloomberg

When Donald Trump gave an interview to Bloomberg Businessweek last month, perhaps the most interesting revelation was his hymn of praise to William McKinley, the 25th president, who was assassinated in 1901. Trump even added a new mountain for Points of Return to use in the economic debate (from Table Mountain to the Matterhorn), by complaining that Mount McKinley, America’s tallest peak, had been renamed Denali. “They took the name off — that was not nice, because he made this country so rich.” McKinley inspires Trump as follows:

William McKinley made this country rich. He was the most underrated president. And those that followed him took the money… But McKinley made the money and he was truly the tariff king.

It’s true that McKinley was America’s most dedicated protectionist of the late 19th century. Trump has called himself Tariff Man, but McKinley went by “The Napoleon of Protection.” In soaring language far beyond anything we’re likely to hear this year, McKinley said: “Under free trade, the trader is the master and the producer the slave… Protection is but the law of nature, the law of self-preservation, of self-development, of securing the highe

When in the House, where he served as chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, he passed what was known as the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890. Subsequently, he defeated the populist William Jennings Bryan in the presidential election of 1896. The Gilded Age was a prosperous period for the US, and the country maintained high tariffs throughout. It’s hard to say that tariffs did much harm. For McKinley, they did a lot of good:

We lead all nations in agriculture, we lead all nations in mining, and we lead all nations in manufacturing. These are the trophies which we bring after 29 years of a protective tariff. Can any other system furnish such evidences of prosperity?

But there are problems with the McKinley precedent that both Mr. Trump and investors trying to position money on the assumption that he wins the election should take into account.

First, the McKinley tariff was very unpopular because it made goods much more expensive for consumers to buy. Tariffs on most imports rose from 38% to 49.5%, and the elimination of levies on coffee and sugar, then thought luxuries, didn’t sweeten the pill. McKinley himself even lost his seat in Congress. In an ironic twist, historians say that Grover Cleveland, the only person to have done what Trump is attempting and come back from a defeat to win a second term, was largely able to win his rematch with Benjamin Harrison in 1892 because voters hated the McKinley Tariff. So it’s not a sure-fire political winner. Trump might be on firmer ground with tax cuts he promised in his convention speech Thursday night; the trade issue is far more complica

The Tax Foundation dug up a report from the New York Times in McKinley’s day that tackled the question — still prevalent — of who pays the tariff.

Let the facts, which are multiplying every day, tell who it is that pays the onerous tariff taxes. They will answer that the American people pay these taxes and that the burden of them rests most heavily upon the poor, inasmuch as there are very few of the necessities of life the prices of which are not increasing on account of the McKinley tariff.

The Times interviewed various New York tailors who all promised that they would raise prices once extra tariffs became payable on the fabric they used. That sounds like political poison in today’s environment, where people are angry about inequality that has grown for a generation and the sharp rise in prices of

That leads to the issue of tariffs’ interaction with the tax system. As Trump told Bloomberg Businessweek: “All he did was tariffs, we didn’t have an income tax.” Higher tariffs, it’s hoped, can enable tax cuts without hurting revenues. Transferring the burden of revenue-raising from American workers to foreign importers sounds great, but the danger, as happened with the McKinley tariff, is that switching from income tax to tariffs would be regressive, with a net move in the tax burden from rich to poor.

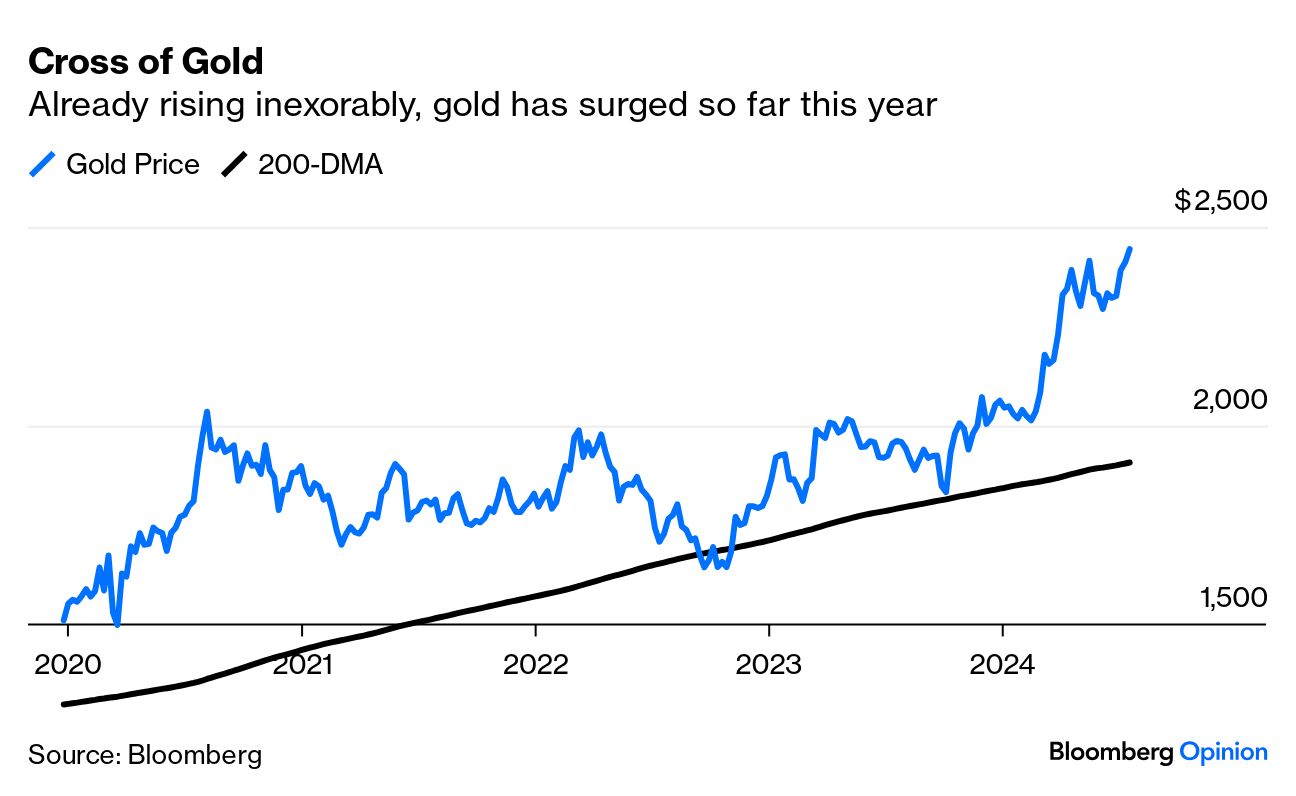

Another important point of difference is that McKinley coupled protectionism with extreme sound money. He signed into law the Gold Standard Act of 1900, effectively giving up the right to devalue. That was intendedto maintain a strong dollar but also meant that the currency couldn’t appreciate to counteract the effect of the tariffs. Trump has made very clear that he wants the dollar to weaken (which raises the price of imports and tends to stoke inflation). That will be hard to achieve. Tariffs are far more workable in an environment of fixed rather than floating exchange rates. And the gold price suggests that investors are positioning for a debasement of the currency:

It’s also open to question whether protective tariffs were particularly central to the Gilded Age growth in prosperity. The libertarian Cato Institute argues firmly that they weren’t, while their role is a major point of contention in economic history. Rather like China in the last quarter-century, a continent was opening up and providing great opportunities for internal trade. The Gilded Age economy was also boosted by a huge influx of immigrants (not a priority under Trump 2.0). It’s possible that protection helped the US in this period, just as it helped China manage its own recent transition, but that’s not clear.

One final irony: If Trump resembles any historic presidential candidate, Bryan, a fire-breathing economic populist and outsider with conservative social ideas, is possibly the best fit. He lost three times while McKinley logged two conclusive victories, so Bryan doesn’t look like the one to emulate. The election of 1896 was a rare choice where high issues of economic policy were front and center. Delegates in Wisconsin this week would probably have preferred Bryan, who wanted to adulterate the currency with silver — famously objecting to being crucified on a cross of gold — and to cut tariffs. They would

For markets, the implication is to stop worrying about whether interest rates follow a Table Mountain flatline or go sharply down like the Matterhorn. Instead, they should contemplate the possibility of a new Mount McKinley of sharply higher tariff protections that would put upward pressure on inflation, bond yields and the dollar. If Trump is really intent on being a second McKinley, he risks inflation and a bond market riot.