ABN Amro giver det store overblik over økonomien og genopretningen efter pandemien. Banken hæfter sig ved, at en række forhold giver modvind for genopretningen. Det er ikke bare Delta-varianten, men også vedvarende forsyningsproblemer og voksende politiske vanskeligheder. Der er slet ikke den opbakning til regeringerne nu som under pandemien. Dog venter banken, at væksten til næste år vil ligge over trenden. Forbruget er dog slet ikke kommet rigtigt igang endnu, og væksten i Kina aftager.

Uddrag fra ABN Amro:https://www.abnamro.com/research/en/our-research/global-monthly-will-headwinds-throw-the-recovery-off-course

Global Monthly: Will headwinds throw the recovery off course?

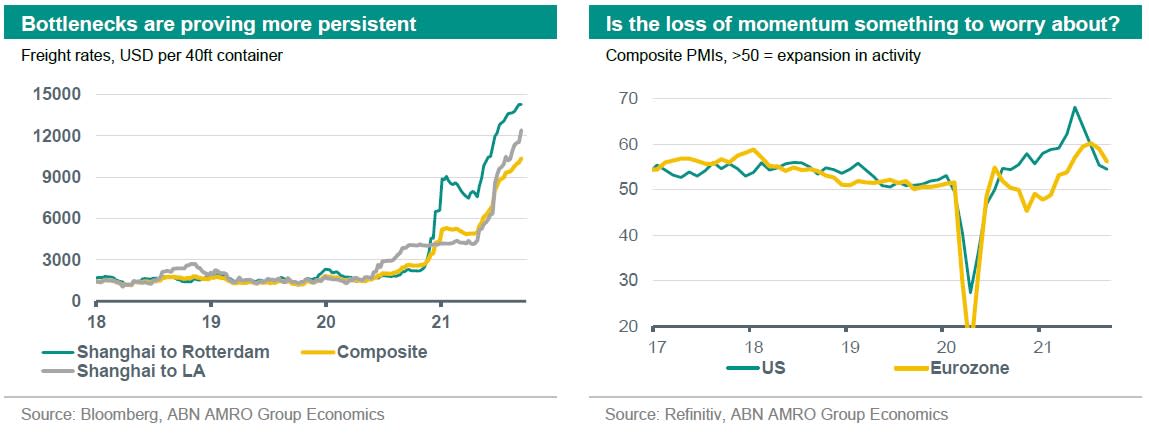

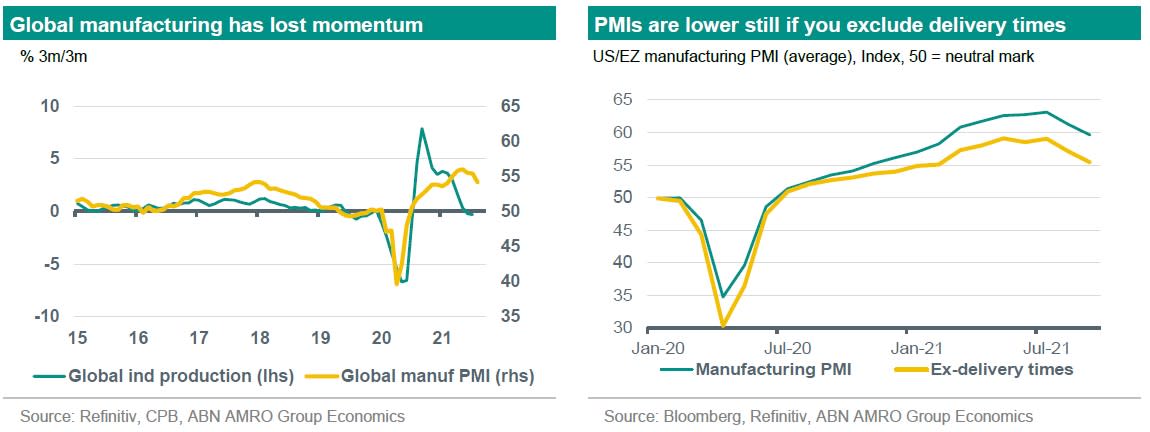

The global recovery has lost momentum, and is facing three key headwinds: 1) the spread of the Delta variant, 2) persistent supply chain bottlenecks, and 3) the unwind of government support. Bottlenecks are now likely to persist into 2022, capping growth in the manufacturing sector.

However, this is also likely to elongate the industrial recovery, and despite the headwinds, we expect growth to remain above trend over the coming year. The services recovery still has a long way to go, and this recovery will be aided next year by the normalisation in labour markets, a pickup in government investment, and some easing in supply side bottlenecks.

Despite the cautious withdrawal of pandemic support measures – with the Fed about to begin tapering its asset purchases, and wage subsidy schemes gradually wound down – both monetary and fiscal authorities will maintain a broadly supportive stance for growth.

The global recovery has lost momentum, and is facing three key headwinds: 1) the spread of the Delta variant, 2) persistent supply chain bottlenecks, and 3) the unwind of government support

Bottlenecks are now likely to persist well into 2022, capping growth in the manufacturing sector

However, this is also likely to extend the recovery. And despite the headwinds, we expect growth to remain above trend, with a services recovery that still has a long way to go

Regional updates: in the eurozone, we look at coalition formation after the German election, and in the Netherlands, the Prinsjesdag budget was light on policy changes from the caretaker government

In the US, upside risks to inflation remain, while the Fed moved a step closer to tapering We lowered our growth forecasts for China, but expect Beijing to contain the Evergrande fallout

In this month’s new Spotlight, we explain what China’s regulatory crackdown means for the outlook

Global View: Headwinds abound – but growth should remain above trend

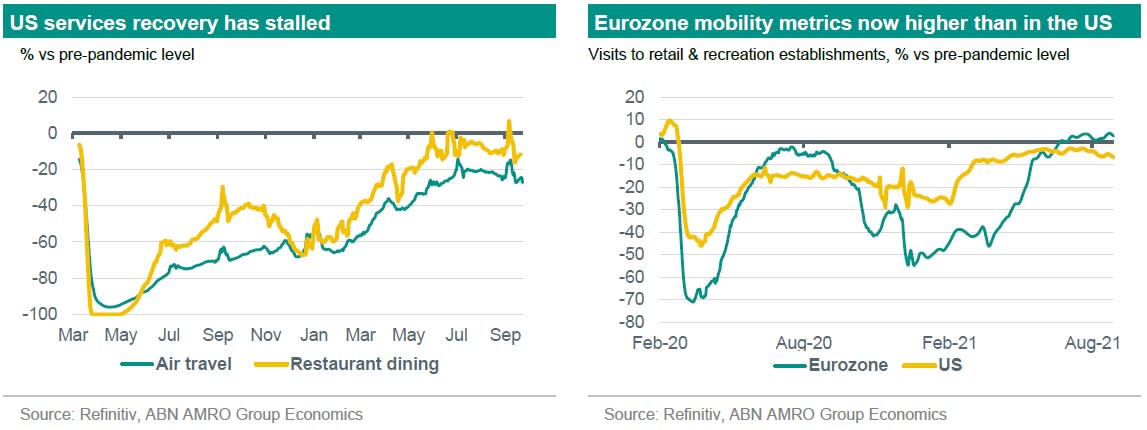

The global recovery from the pandemic is entering a new, and likely more turbulent phase. The ‘low hanging fruit’ of the reopening rebound is now behind us, and while there is still much room for economies to recover, the headwinds have become more pronounced. The more immediate of these is the spread of the Delta variant. This has driven a loss of momentum in the US services recovery, and dampened consumer sentiment.

In China, the reimposition of restrictions in pandemic hotspots has led to a likely stalling in economic growth in Q3, and we have downgraded our growth forecast for 2021 on the back of this. Another headwind for the global economy is the supply-side bottlenecks linked to the reopening, which have proven more stubbornly persistent than initially thought. We expect these bottlenecks to continue constraining activity well into 2022.

The third and final key headwind to watch is the unwind of government support measures. September is a crucial month for this in the US, where unemployment benefit top-ups will expire, and in the Netherlands and the UK, where wage subsidy schemes will formally end. For most eurozone countries, this headwind is rather less pronounced, with support continuing to unwind only gradually. What does all of this mean for the outlook going forward?

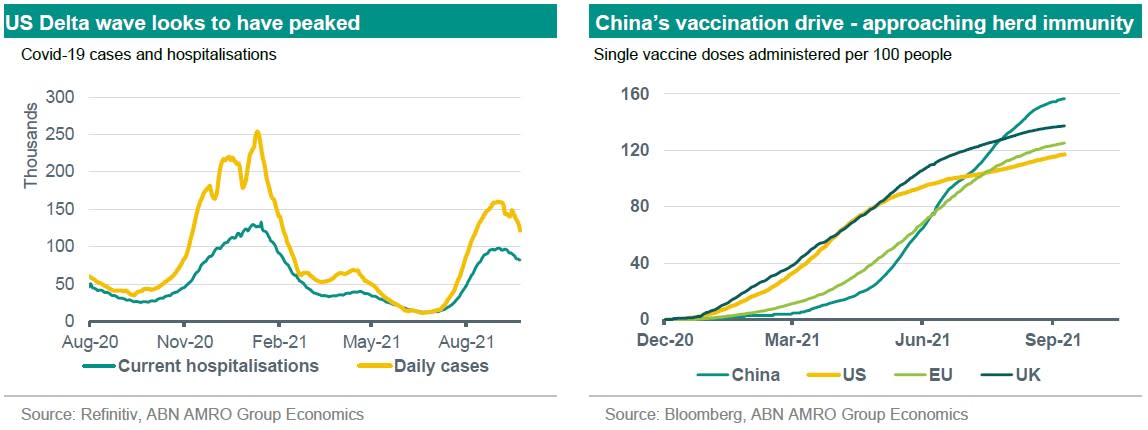

Damage from Delta: Visible in the US, significant in China, but limited in the eurozone Although the Delta coronavirus variant hit European shores sooner, the wave of infections – and the burden on hospitals – has been much bigger in the US. Correspondingly, so has the economic impact.

While there have been no new restrictions on activity, consumers have themselves become more cautious. This is most visible in the collapse in consumer confidence since August, with the Michigan survey falling to a near 10-year low. We also see a loss of momentum in the services recovery in the US, with the most pandemic-sensitive sectors such as air travel and restaurant dining stuck stubbornly below pre-pandemic levels.

This contrasts with the eurozone, where a more cautious reopening combined with higher vaccination rates has helped to contain the spread of Delta, and where the services recovery appears to have continued apace – Google mobility data shows visits to retail & recreation establishments overtaking those in the US, where such visits remain below pre-pandemic levels. Moreover, consumer confidence in the eurozone has remained at historically high levels.

In China, the government’s hardline approach towards even minor Delta outbreaks has significantly dented the recovery, with regional lockdowns and travel restrictions during the busy summer season. This was evident in the August activity data, which showed a sharp fall in annual retail sales growth, driven by services categories such as eating out. We now expect hardly any quarterly growth in Q3, and although a rebound is likely in Q4, this has led us to cut our 2021 growth forecast to 8.3%, from 9.0%.

Could a winter resurgence derail things?

What can we expect going forward? We think we have likely turned the corner with Delta, and that the impact in the US and China should fade over the coming months.

First, both case numbers and hospitalisations have peaked in the US, and some epidemiologists have suggested that the summer wave has likely brought forward a large number of cases that would have happened over the winter; by November, models suggest case numbers will be back at early summer levels.

Second, vaccination rates continue to rise in both the US and China, with China expected to reach herd immunity by year end, while in the US a combination of vaccinations and natural immunity should blunt any winter wave. In the eurozone, while a winter wave among the unvaccinated remains a risk, stricter rules banning entry to restaurants and major events to the unvaccinated (unless they pay for frequent covid tests) are likely to maintain pressure on the vaccine hold-outs to get jabbed. As such, we do not view another pandemic wave as a serious risk to the eurozone outlook.

Bottlenecks are dampening growth from multiple angles

A more persistent risk to the outlook, in our view, instead comes from the supply chain bottlenecks, including the semiconductor shortage and the disruptions to shipping. Aside from the upward pressure on inflation – a topic we covered in our August Monthly – these bottlenecks have also put a dampener on growth, via a number of channels.

First, the global industrial upswing has lost momentum, evident in both hard (industrial production) and soft (PMIs) indicators. This was confirmed in the September flash PMIs for both the eurozone and the US, which – although still elevated – pointed to a further slowdown in manufacturing. If we strip out the effect of the record lengthening in delivery times from these, which has an upward effect on the headline PMI, the slowdown has been even more marked.

Bottlenecks also seem to have hampered investment, which was surprisingly weak in the US and some eurozone economies in Q2. It goes without saying that all of this is not for lack of demand: the sub-indices for new orders remain elevated across regions, and on the consumer side, demand for goods in the US remains well above trend, while in the eurozone demand has recovered back to trend.

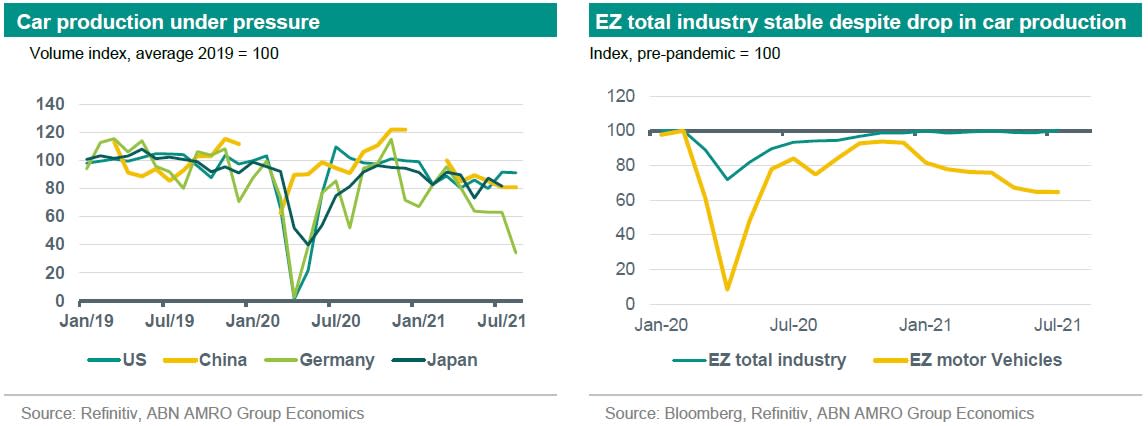

Germany particularly hard hit by auto sector disruption

The semiconductor shortage has had a particularly marked effect on the car industry, with automakers across the globe implementing production stops. For this sector, growth has not merely slowed, but we are seeing sharp contractions in output.

For instance, in Germany – which has been especially hard hit – car production is down by more than 60% from its peak early this year. Given the size of the sector in Germany (1/5 of industrial production, and around 5% of GDP), the drop in car output has been enough to pull total industrial production lower (-0.7% 3m/3m as of July), despite every other sector continuing to expand.

In contrast, production at the eurozone aggregate level – of which cars has a much smaller share – has been more or less stable, but the collapse in car production has clearly taken the wind out of the manufacturing sector’s sails. In the US, car production has also fallen, although not by nearly the same degree.

Given that it also has a much smaller share of overall production (at around 4%), the weakness in the US has not been enough to prevent continued expansion in manufacturing, which as of August was up 1.5% 3m/3m. These supply chain bottlenecks have proven more persistent than initially expected, and we now foresee problems continuing well into next year.

Indeed, lead times for semiconductors are reported to have risen further, reaching 21 weeks last month (compared to an average of around 12 weeks in the pre-pandemic year of 2019). The shortage in semiconductors has been exacerbated by plant closures in Malaysia and Vietnam, which have been under strict lockdowns linked to the Delta variant spread.

With regards shipping – and the seven-fold rise in container freight tariffs – several global shipping lines have indicated recently that they will stop increasing spot freight rates. With that said, it is difficult to foresee rates falling back to pre-pandemic levels any time soon, with the industry still struggling to contain the impact of port congestion and temporary closures linked to virus outbreaks (notably in China/Asia).

Ultimately, these bottlenecks will of course ease. When this does happen, it is likely to provide a significant tailwind to industries that have struggled to keep up with demand, and we think this could even elongate the recovery. In the meantime, however, global manufacturing growth will remain constrained.

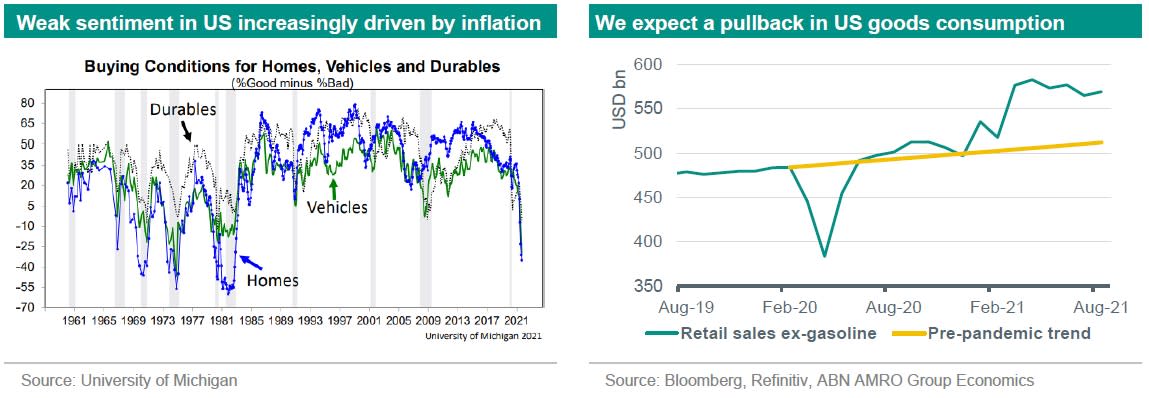

Early signs that inflation could start to hit consumer demand

An easing in manufacturing bottlenecks cannot come soon enough for consumers, who – particularly in the US – have had a seemingly insatiable demand for goods. Indeed, despite goods consumption being well above trend for more than a year now, retail sales unexpectedly rose again in August.

In the eurozone, this risk is much lower, but still significant. Although core inflation has been much more benign, the run up in energy prices – which this month led us to substantially raise our forecasts – is leading to falls in real wages in some economies.

This is one reason for our below consensus growth forecast for next year (3.8% vs 4.3%).

Unwind of government support: Could a headwind become a tailwind?

If all of these headwinds were not enough, there is also the unwind of government support measures to contend with. September is a crucial month in this regard; in the US, generous unemployment benefit top-ups expire at the federal level (they had already expired in around half of US states), while in the Netherlands and the UK, the wage subsidy schemes that have helped millions of workers retain their jobs through the pandemic will formally end.

As a base case, we do not expect a ‘cliff edge’ type impact from the end of these support measures – with a sudden surge in bankruptcies and unemployment – to result. Economies have for the most part fully reopened, with only very specific sectors – such as airlines, for instance – still facing significant revenue shortfalls.

In Germany, the short-time work (STW) scheme in its current shape will not end before the end of this year, but companies have already reduced their use of the scheme significantly (the share of employees in STW has declined from around 8.5% in February to just 2% in August).

In France, financial support for companies with employees in STW gradually become less favourable (and in line with the changes in activity) from June onwards. The share of employees in STW in France dropped from 15% in April to 3% in July. We expect a temporary hit to incomes in the US from the expiration of benefit top-ups, of which around 10mn were still in receipt as of early September.

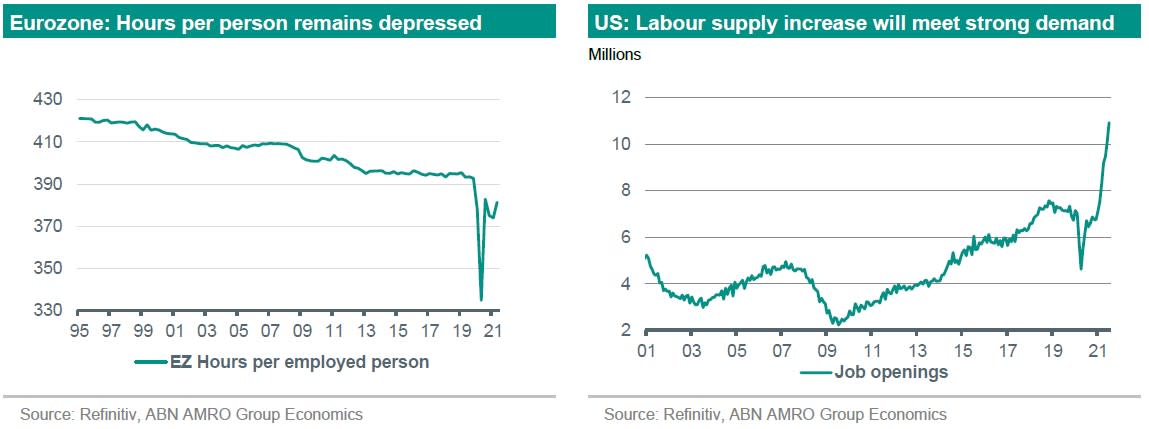

In the eurozone, we also expect a rise in unemployment over the coming months, as businesses make painful adjustments to the new post-pandemic normal. Here, many are still working less than their usual hours, suggesting more slack than headline unemployment indicates.

However, the rise in labour supply in the US and many eurozone countries will be met with very strong demand for labour, with job vacancies surging in recent months. Indeed, one of the main supply-side bottlenecks we have written about in the past has been in the labour market, and the early end to unemployment benefit top-ups in many US states was precisely in response to complaints from businesses that support was preventing people from returning to the labour market, leading to labour shortages. As such, the gradual pullback of government support could well prove to be a tailwind that helps economies along the recovery and adjustment path.

Conclusion: Headwinds are significant, but unlikely to derail the global recovery

All told, the outlook for the global economy remains strong. To some extent, the slowing we are seeing now was inevitable following the initial reopening bounce, and consistent with our base case. The combination of headwinds we have outlined here are putting an additional dampener on growth, while posing downside risks to the outlook.

Despite this, we continue to expect above trend growth to continue well into 2022, and after the current soft patch we expect the recovery to regain some momentum next year. While goods consumption is due a healthy correction, the services recovery has a long way to go before consumption returns to the pre-pandemic trend. The passing of the Delta wave is likely to give the services sector – which makes up the bulk of private consumption – a renewed boost.

Growth will also be helped by higher government investment, with Biden’s infrastructure spending plans in the US likely to start kicking in, and with the Recovery Fund in the eurozone starting to disburse to member states. At the same time, while supply bottlenecks have proven more persistent than expected, they are still likely to ease to some extent in 2022, and this should give a new tailwind to the recovery, given the likely significant pent-up investment demand.

Finally, the normalisation of labour markets should also aid the recovery, and by the end of the year many economies should be back near pre-pandemic levels of employment. In the near term, however, the global economy could be in for a bumpy ride.