Resume af teksten:

Klimaændringer påvirker kortsigtet inflation i euroområdet, hovedsageligt gennem overgangsrisici som energiskatter og udsving fra ekstreme vejrhændelser. ECB vurderer, at grønne skattemæssige tiltag vil tilføje 0,2 procentpoint til inflationen i 2024 og 2025, mens udvidelser af emissionshandelssystemet kan øge inflationen med 0,4 procentpoint i 2027. De seneste varme somre, kendetegnet ved stærke hedebølger og tørke, har hævet fødevareinflationen med 1-2 procentpoint. Fødevareprisinflation i eurozonen ligger nu på 3,2%, betydeligt over det historiske gennemsnit. Global opvarmning øger sandsynligheden for ekstreme vejrforhold, hvilket kan have mere vedvarende indflydelse på fødevarepriserne i fremtiden. Samtidig bidrager ophøjede fødevarepriser til højere husholdningsinflationsforventninger, selvom ECB ikke forventes at reagere med rentestigninger. I Holland har fødevareinflation også været bemærkelsesværdig høj, primært på grund af forhøjede punktafgifter. Både på europæisk og lokalt plan forventes fødevarepriser at forblive forhøjede i de kommende år, hvilket kunne have betydning for inflationsforventninger og politiske beslutninger.

Fra ABN-Amro:

The short-term impact of climate change on inflation often is analysed by looking at transition risks, such as the impact of carbon pricing and its consequences for energy price inflation. For instance, in its December 2024 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the eurozone[1], the ECB estimates that national green discretionary fiscal measures (e.g. carbon pricing and energy taxes) added 0.2 percentage points to eurozone inflation in 2024 and will add a similar amount in 2025. Moreover, ECB staff project that the expansion of emissions trading to heating of buildings and transportation could add up to 0.4pp[2] to inflation in 2027. In contrast to transition policies, the impact of acute and chronic physical climate risks on inflation is considered to be significant only in the medium to longer term. Still, climate and weather-related hazards, such as temperature extremes, storms, floods, drought and wildfires is rising and its economic damage are increasing. Consequently, global food prices have occasionally been lifted by extreme climate and weather-related events. As climate change is expected to increase the intensity and frequency of various extreme weather events in the coming years, the impact on inflation should also become more significant. In this note we analyse the short-term impact of acute physical climate risk on food prices and headline inflation in the eurozone.

Food inflation has been on the rise again recently. In this note, we explore an emergent driver of food prices: climate change

The short-term impact of climate change is often analysed through the lens of transition risks and carbon pricing on energy price inflation

However, the impact of climate- and weather-related disasters, such as temperature extremes, storms, floods, droughts, and wildfires, on food price inflation has become increasingly urgent

The 2025 European summer was once again characterized by heat, drought, and wildfires, suggesting that eurozone food price inflation was likely fueled by around 1–2 percentage points and will remain elevated over the coming years

Household inflation expectations are more sensitive to food inflation, making it important for the ECB to keep a close eye on

However, we do not foresee this being a trigger for rate hikes

Dutch food inflation remained elevated in 2024 and early 2025, largely driven by increased excise duties. Weather-related events could cause a lift to CPI headline inflation of 0.15-0.3pp

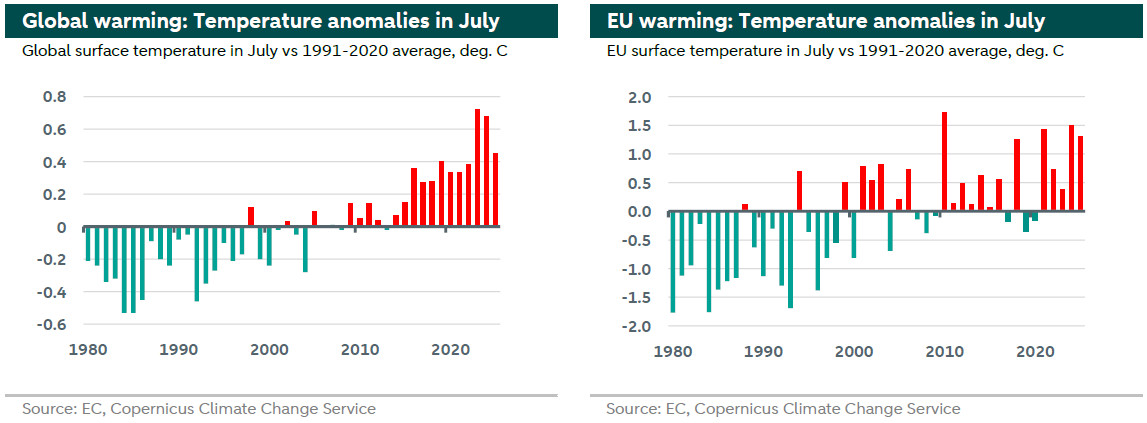

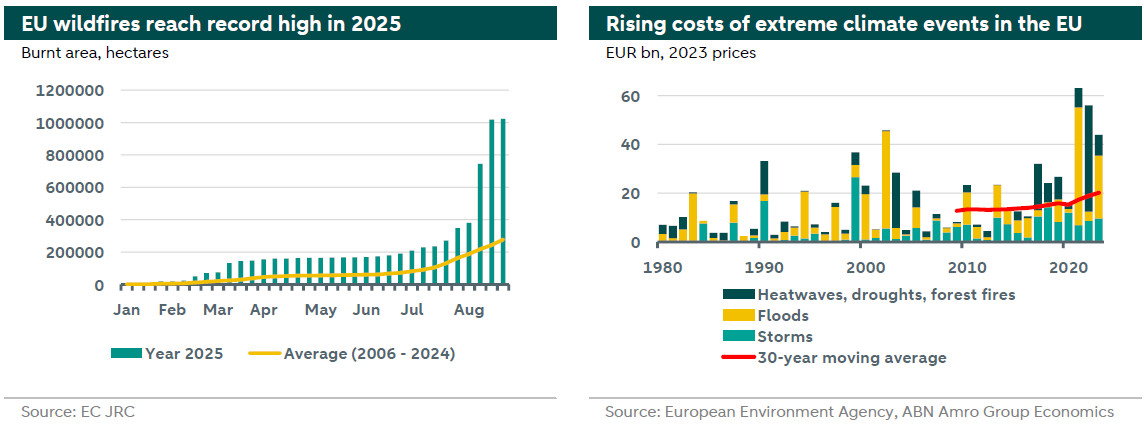

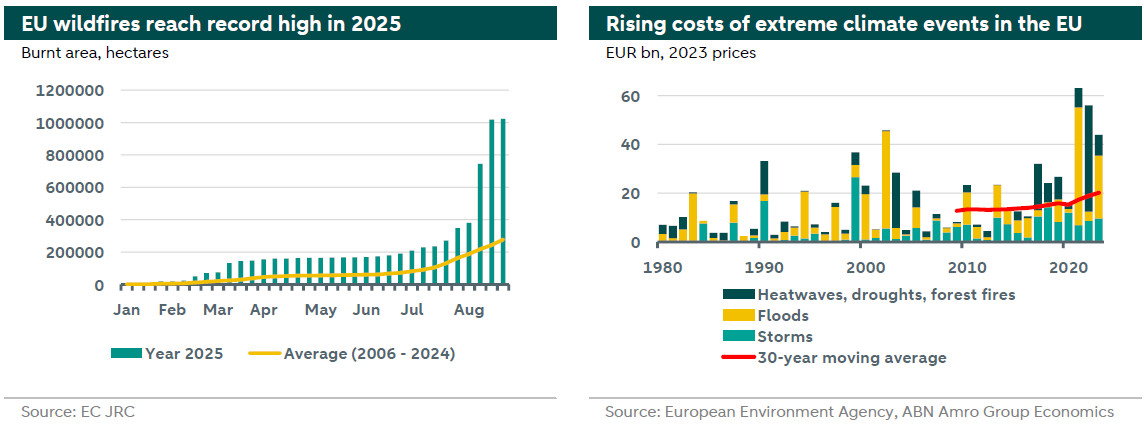

Global warming is continuing gradually, with July 2025 being the third-warmest July globally (after July 2023 and 2024) (see for instance here and here ). As the left and right graph above illustrate, in July 2025, the global land surface temperature was 0.45°C above the 1991-2020 July average, and the European land surface temperature 1.30°C above its 1991-2020 average. This rise in the average global temperature has resulted in more frequent episodes of extreme drought and wildfires. Besides the land surface temperature, the average global sea surface temperature was also the third highest on record in July, which contributes to more frequent precipitation extremes and floodings (see for instance here , here and here ). Meanwhile, the annual economic losses from weather- and climate-related extremes in Europe have risen to around EUR 50-60 bn in the past few years, which is equal to 0.3-0.4% of GDP (see bottom-right graph below).

Food price inflation is lifted by climate and weather relates extremes, but there are wide differences between regions and countries

Extreme climate and weather related events have had significant impact on food prices in the past few years. Two working papers by the ECB ( here and here ) assess the effects of temperature extremes and weather shocks on food prices and headline inflation globally and at the European level. The papers find that the impact on inflation of weather shocks (both measured as changes in mean temperatures and in temperature variability) varies considerably across countries and regions. Nevertheless, the ECB’s models find that hot summer events have a ‘significant, meaningful and longer-lasting impact on inflation, with the main channel of transmission operating via food prices’, with little or no impact in other seasons. Indeed, the ECB’s estimates find that global food prices on average rise by 0.4-0.6 percentage points in the first two quarters after a ‘hot summer event’, where the temperature exceeds the country’s historical average (1951-1980) by at least 1.5°C. That said, the impact can vary widely at the regional or country level. Generally speaking the impact is larger in countries with already relatively high summer temperatures. Also, the ECB finds that the impact on prices is non-linear, increasing with higher absolute temperatures and with the size of the temperature shock.

The ECB’s results seem broadly consistent with the results of a joint study by the ECB and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research ( here ), which finds that extreme summer heat increased food price inflation in Europe by 0.4-0.9 percentage points in 2022. Based on the size of the temperature anomaly in 2025 and the model estimates of the impact on food price inflation, we think that the upward impact of the hot summer on food price inflation could be in a range of roughly 1-2 percentage points this year. Considering that this year’s summer was relatively hot as well, it seems that the impact on food prices probably was roughly the same as last year. However, as the model results have shown that the impact of hot summers on food price inflation is non-linear and also rises with higher absolute temperatures, the impact probably was a bit stronger than in 2024.

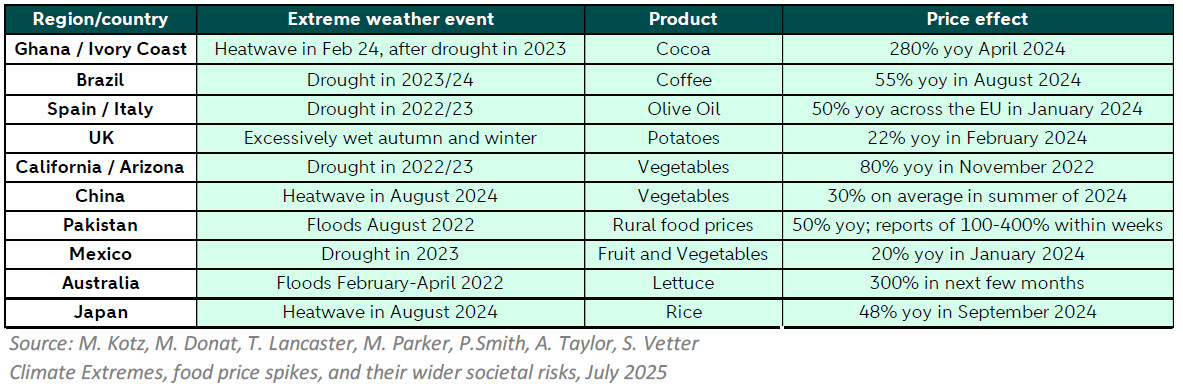

These model based estimates focus only on the impact of temperature extremes and do not include the impact of, for instance, floodings, which can also have a noticeable impact on food prices as the table below shows. Therefore, the estimates probably are lower-bound estimates of the total impact of climate and weather related extremes on food prices.

Next to the model-based estimates of the impact of extreme weather events on inflation there also is factual evidence. A study led by the Barcelona Supercomputing Center ( here ) has collected numerous examples since 2022, in which food prices of specific goods spiked in response to heat, drought or heavy precipitation extremes. Some selective examples are presented in the table below.

The impact of these particular events on eurozone inflation crucially depends on the weight of the item in the HICP basket, the import share of the product from the disaster struck country, and the possibility of substitution to other suppliers or other products. Therefore, it will differ per event and is hard to exactly estimate. That said, global warming is expected to result in more frequent and more intense climate and weather related extremes globally, indicating that the impact on eurozone inflation probably will become more significant in the next few years, keeping food inflation elevated. While some adaptation measures are to be expected over time, the study previously cited by the ECB and the Potsdam Institute finds that historical adaptation to temperature increases and adjustment to warmer climate conditions has so far been limited.

Food inflation has been on the rise again in the eurozone lately. After hitting a post-energy crisis trough of 2.3% in July 2024, food inflation reaccelerated in the autumn of that year (consistent with the dynamics outlined above), and this year it began reaccelerating already in February. As of August, it is near a post-energy crisis high of 3.2% – well above the historic (2010-19) average for food inflation of 1.8%. Aside from the climate effects discussed above, there are likely other factors driving food inflation at play. For instance, pass-through of higher wage growth, which has been particularly high for lower income workers that make up a large part of the food industry. However, a significant driver has likely been the hot summers and the impact on food supply that this has had. For instance, we estimate the surge in olive oil prices alone pushed up food inflation by c0.2-0.3pp at its peak in 2024. Food prices have around a 19% weight in the overall HICP basket for the eurozone. So, assuming the model estimates of the impact of weather events holds of a c1-2pp rise in food inflation, headline inflation would see a lift of as much as 0.2-0.4pp compared to a scenario without climate/weather-related effects.

Indeed, we expect food inflation to stay relatively elevated over the coming year (see chart below), and likely beyond our forecast horizon given the model results outlined above (which also indicate that the effects on inflation are ‘long-lasting’). This is also consistent with the recent rise in global agricultural commodity prices. Having been relatively stable following the energy crisis-linked spike in 2022, global food commodity prices have been on a steadily rising trend since, and are now rising around 8% y/y (dairy prices are up 21% y/y). Eurozone food inflation is largely driven by local factors and so does not have a 1:1 relationship with global prices, but higher global prices are still likely to have spillover effects to European food prices.

Elevated food inflation will be an important offset to the looming undershoot of the ECB’s 2% target, which to a large extent is driven by energy prices and the stronger euro. Food inflation is also important for household inflation expectations formation. Indeed, research has shown that households tend to be more sensitive to food prices, making it an important driver of inflation expectations. To the extent that higher expectations feed through to higher wage demands, this could be concerning for the ECB and in theory may even warrant a policy response. On balance, however, we judge that inflation expectations should remain contained on current trends. Firstly, given that food is an essential item, there is likely to be a limited demand response to prices, meaning that food simply takes up a larger share of the consumption basket and households reduce consumption elsewhere. This could [Av1] put some offsetting downward pressure on other inflation categories. Second, the strong euro helps to cap imported inflation (including food), and the euro is expected to strengthen further still next year, rising to $1.25 by end 2026[Av2] from around $1.17 at the time of publication. Moreover, oil prices could fall further due to the supply glut. Indeed, it could be said that food price jump is hitting at a time when circumstances are otherwise benign in terms of inflationary pressures. Given this, in our base case we do not foresee the ECB raising rates in response. With that said, higher food inflation poses a persistent upside risk for inflation in the future, and if other factors turn out less favorable (e.g. oil, euro) and growth is stronger, this could imply a tighter policy stance.

Dutch food inflation to stay elevated despite easing one-off effects

A eurozone country where food inflation has been particularly high is the Netherlands. Dutch food inflation remained elevated in 2024 and in early 2025, largely driven by increased excise duties on tobacco, alcohol and the so-called ‘sugar tax’. We estimate that approximately half of the contribution of food inflation to total inflation stemmed from these excise duty hikes, with tobacco being the largest contributor. While the tobacco tax was introduced in April, its impact on inflation only became visible somewhat later as companies could first sell their old inventories at the previous rate. The base effects (as inflation is measured y/y) mean the one-off increases have now faded from Dutch food inflation figures, bringing it more in line with the broader eurozone.

Similar to what we described above for the eurozone, Dutch food inflation[3] has recently been on the rise again after reaching a low mid-2024, climbing to a 3.7% in August this year which is well above the 2010-19 average of 1.28%. Climate factors have likely played a significant role, with hot summers disrupting food supply. Commodities account for roughly 45% of total costs for food producers in the Netherlands (read more about the sector food here and here ). Climate change increases volatility in for instance cacao, vegetable and coffee markets, and since many food commodities are purchased in dollars a fluctuating exchange rate adds to cost uncertainty. Additionally, elevated food inflation is likely also influenced by other factors such as elevated wage growth – which reached historic highs in the Netherlands following the inflation spike – and is likely (partly) passed on to consumers.

Food prices have a weight of around 14.5% in the Dutch CPI inflation basket. Assuming weather-related events cause a c1-2pp rise in food inflation, the CPI headline figure in the Netherlands would see a slightly smaller lift than the eurozone aggregate, at 0.15-0.3pp [4]. Therefore, as with the eurozone, we forecast somewhat higher food inflation in the Netherlands compared to the 2010-19 average.

As described above, households tend to be sensitive to food prices. With headline inflation still higher than in the eurozone, elevated food prices could pose a risk to household inflation expectations and with that wage demands. Our base case is still for expectations to normalize in line with the gradual decline of the headline inflation rate.

Model based estimates as well as factual information about the impact of climate and weather related extremes on food prices and inflation indicates that eurozone food price inflation will be fuelled by the hot summer weather. The impact on food prices probably will be in the range of roughly 1.0-2.0 percentage points in 2025H2 and eurozone headline inflation would see a lift of as much as 0.2-0.4pp. Due to the smaller weight of food prices in the CPI inflation basket, Dutch CPI headline inflation could see a somewhat smaller lift at 0.15-0.3pp. Trends in eurozone food inflation could have implications for ECB policy if it were to have a meaningful impact on household inflation expectations, though we do not foresee this in our base case.

[1] link ECB

[2] link ECB

[3] We refer here to the CPI series without government intervention, to distinguish between the increased excise duties and general food inflation.

[4] While the impact on food inflation is larger for countries that have already relatively high summer temperatures, the Netherlands is also affected because of its position in global supply chains as well as risk of draughts.

Hurtige nyheder er stadig i beta-fasen, og fejl kan derfor forekomme.