Resume på dansk

Gulds rekordstigning handler ikke kun om inflation. Ifølge Simon White fra Bloomberg er det et signal om, at markedet løber tør for “sikker” pant/sikkerhed (collateral) og derfor søger noget uden modpartsrisiko. Guld – især når det ejes uden for det finansielle system – er ingen andens forpligtelse og fungerer som “ubestridelig” sikkerhed, når både statsgæld og kredit ser mere risikable ud.

Hvorfor guld – ikke kun inflation

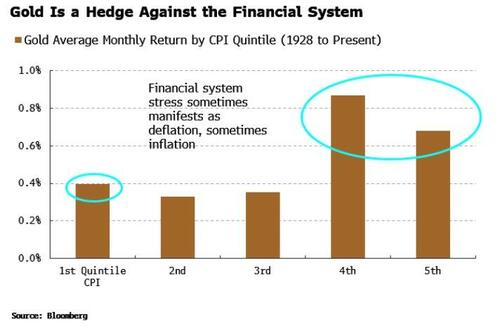

Ikke kun inflationsværn: Guld beskytter også i deflation og generel finansiel stress. Pointen: inflation/deflation er symptomer; problemet er svækket tillid til finansielt pant.

Ingen modpartsrisiko: I “ikke-finansialiseret” form er guld ikke nogens gæld. Det gør det attraktivt, når kvaliteten af andet pant (stats- og virksomhedsobligationer, kredit) kommer i tvivl.

Hvad startede bevægelsen?

Efter Ukraine-krigen begyndte især emerging-market-centralbanker at købe guld, fordi dollarreserver blev opfattet som politisk sårbare. Denne adfærd har bredt sig til det øvrige marked.

Historien viser: guld virker også i deflation

I 1930’erne steg guldet under dyb deflation. USA tvang dog private til at sælge guld til staten og revaluerede prisen bagefter, så gevinsten tilfaldt ikke befolkningen. Pointen: uden markedsindgreb ville guld sandsynligvis have steget endnu mere.

Hvilke risici driver efterspørgslen efter sikkert pant?

White nævner en række mulige udløsere, som alle kan underminere værdien af det pant, markedet normalt bruger som “penge”:

Stor kreditnedtur

Obligationschok efter en periode med kunstigt lav rentevolatilitet

Monetisering af meget store statsunderskud (QE tilbage kort efter QT)

Funding-stress i pengemarkederne

AI/aktie-boble der brister

Recession

Told/geopolitiske spændinger

Kreditmarkedets advarsler

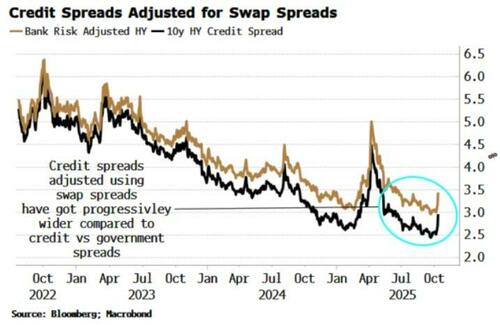

Spreads er længe blevet presset ned af jagten på afkast og konkurrence fra private credit – men det betyder ikke lavere risiko.

Spreads måles mod “risikofri” statsrenter, men med store fiscal deficits er den risikofri reference mindre sikker.

Korrigeret for swap-spreads (hvad det koster banker at bære risiko) ser kreditspreads reelt højere ud.

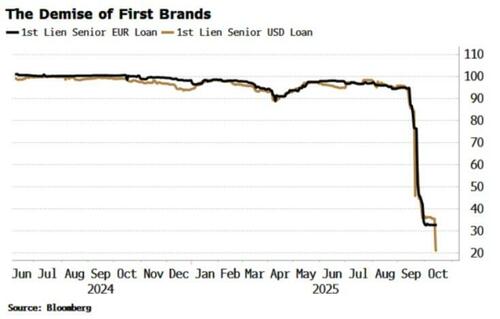

Nye stød (fx øget USA-Kina-handelstension og en stor konkurs) har fået spreads til at stige igen. Som Jamie Dimon siger: ser du én kakerlak, kommer der ofte flere.

Staternes rolle og renter

Markedet frygter, at gigantiske underskud til sidst må finansieres via pengeskabelse (QE/monetisering), som udhuler fiat-penges købekraft.

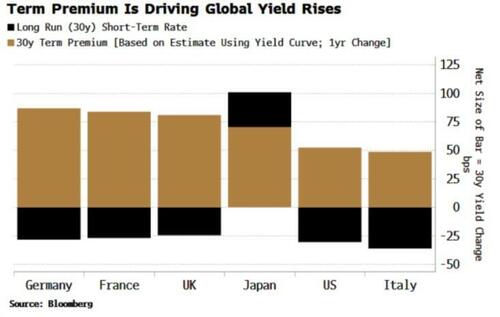

Term premium er steget og har trukket renterne op det seneste år, et tegn på svagere tillid til statsobligationer som pant.

Lav rentevolatilitet nu kan være forspil til et større ryk i renter – op eller ned. I begge tilfælde giver guld mening:

Ved inflation: klassisk værn mod udhuling.

Ved deflation/kreditkrise: mangel på “money-good” pant – guld fylder hullet.

Hvad kan ske i en hård stressfase?

Virksomhedsgæld rammes først i en kreditkrise, men til sidst kan også statsgæld blive problematisk, hvis stater må trykke penge for at holde nominalværdien oppe. Den reelle værdi bliver så udhulet.

Guld bevarer derimod sin status som “money good”, så længe det ikke igen konfiskeres politisk.

Konklusion

Guldets stærke stigning er et system-signal: markedet mangler sikkert pant og ser stigende systemiske risici for både privat og offentlig gæld. Derfor giver det mening for flere aktører at eje guld som sikring mod finanssystemet – ikke kun som et simpelt inflationsværn.

Original analyse:

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

The historic rise in gold signals that the market is scrambling for safe collateral as it takes a growing list of risks increasingly seriously…

Gold is the most misunderstood asset. It is treated with contempt by many investors, a “barbarous relic” in the words of Keynes, an embarrassing, primitive throwback to the days before the thrill of convertible bonds, SPACs and bitcoin. But when it speaks loudly, as it is doing today, it’s wise to pay attention.

One of the biggest misconceptions is that gold is solely an inflation hedge and a protection against currency debasement. But it’s much more than that: it’s a hedge against the financial system. Owned in a non-financialized form, gold is no-one’s liability, and a source of unimpeachable collateral when government debt and on and off-market credit become, as they are now, increasingly risk-laden prospects.

The hunt for safer collateral was sparked off by emerging central banks in the wake of the Ukraine war. The dollar could no longer be deemed a reliable reserve in a world where the US was willing to brandish it as a weapon. What began with central banks has widened to the market in general, seeking safer collateral in a financial system rife with mounting risks.

The critical message gold is sending will be missed altogether if it’s viewed simply as an inflation hedge. Gold is also a deflation hedge. But inflation or deflation are merely the symptoms of rising stress in the financial system. The remedy is high-quality collateral, which the market is currently crying out for and driving the gold price higher as a result.

The conventional view of gold as simply an inflation hedge would mean that the bars in the chart above grew progressively taller as we move from left to right, as higher inflation would be expected to mean better gold returns. But instead, we see that gold performs best when inflation is very low as well as when it is very high.

The effect would likely be even more pronounced if in the early 1930s the US had not forced private holders to sell their gold to the government for a little over $20 an ounce, only to then revalue it to $35. Gold therefore rallied in the entrenched deflation of that decade, even if the general population did not benefit, but it likely would have risen far more if the market had not been shuttered.

The US seized gold as people had begun to hoard it in the Great Depression, worsening the deflationary crisis. What could be causing the market to hedge against a loss of real wealth today, taking gold’s price to new highs? There is no shortage of possibilities:

- A major credit downturn

- Bond shock after low and repressed fixed-income volatility

- Monetization of increasingly large fiscal deficits around the world

- Funding-market event

- AI and equity market bubble burst

- Recession

- Tariff/geopolitical risks

What all of these have in common is that in extremis they could seriously impair the value of the collateral that in the market functions as money. Owning gold starts to make sense if you are beginning to run out of viable, safe options.

The metal’s rise, according to Russell Napier of Orlock Advisors, is chiefly down to an impending credit crisis. It is certainly a strong candidate.

Both high-yield and investment-grade credit spreads have been tightening relentlessly. The hunt for yield and competition from off-market private credit has driven spreads ever lower. But that does not mean risks are declining.

Spreads are measured against “risk-free” government bond yields. But, with massive fiscal deficits in the US and abroad, that cannot be taken for granted. Credit spreads are notably higher after adjusting them using swap spreads to reflect at what level the private market funds at, as the cost of warehousing risk on bank balance sheets has risen.

The need for good collateral means that some of the highest-quality credits are starting to look a safer alternative to government debt.

Or at least they were starting to look safer. Spreads recently widened after renewed trade tensions between the US and China, and the bankruptcy of First Brands, a $10 billion liability firm where over $2 billion was said to have simply “vanished.” As JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon reminded us, when you see one cockroach, you’re likely to see others.

The gold market is consistent with Dimon’s view. In a deflationary credit event where cash flows cease or are seriously impaired, owning a non-financialized asset that’s no-one’s liability becomes one of the few hedges in town.

But it’s not just the private sector’s ability to pay back debt that is feeding market unease, ever more profligate governments are also a major concern. The difference being that sovereigns can print their way out of trouble.

That is undoubtedly also feeding some of the demand for gold. The risk that the largest fiscal deficits seen outside of war or recession are eventually monetized would eviscerate the real value of fiat money. It may be that in response to a private or public debt crisis QE is back on the table alarmingly soon after QT ends, as Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell this week hinted would soon be the case.

The waning confidence in government collateral can be seen in the rise of term premium, which has driven all of the increase in yields over the last year in most major developed-market countries.

The Treasury market is at a key juncture, with low volatility signaling a bigger move in yields is ahead. And whether that move is up or down – due to an inflationary or deflationary shock – gold will still be in demand.

Why? If it’s inflation, then gold can fulfill its better-known function as a hedge against debasement.

But if it’s a credit crisis and deflation, there is a still an essential need for high-quality collateral.

Non-government debt would be hit hard in a credit downturn, but eventually government debt would be too. The need to monetize sovereign obligations in the face of sky-high deficits and an economy in the midst of a debt-deflation would become unavoidable.

Government debt’s nominal value would be underwritten, but its real value would be shredded. Collateral across the board would therefore be hit. But gold, unless it is once again confiscated by fiat, stands to remain “money good.” That’s what its historical rise is telling us

Intro-pris i 3 måneder

Få unik indsigt i de vigtigste erhvervsbegivenheder og dybdegående analyser, så du som investor, rådgiver og topleder kan handle proaktivt og kapitalisere på ændringer.

- Fuld adgang til ugebrev.dk

- Nyhedsmails med daglige opdateringer

- Ingen binding

199 kr./måned

Normalpris 349 kr./måned

199 kr./md. de første tre måneder,

herefter 349 kr./md.

Allerede abonnent? Log ind her