Uddrag fra Authers:

All agree that bloodshed in Gaza and Israel in itself need have no impact on world markets. The issue is whether the war escalates from here, making this a classic example of a low-probability extreme event. Markets always have difficulty pricing such risks. So is the calm response a dangerous underreaction, or is the market’s sang-froid justified on this occasion?

Here are the arguments on either side, summarized as best we can.

The Market Has This Right

Scenario analysis is helpful here. Louis-Vincent Gave of Gavekal Research suggests that Israel has three broad options. It can pulverize Gaza with a bombing campaign (to turn it into something like Tokyo or Dresden in 1945), or it can send in its troops to root out the terrorists door-to-door (also a potentially disastrous outcome for Israel that would horrify the rest of the world, entail great loss of life among conscript soldiers, and carry the serious risk of defeat), or the country can take a third option:

Wait it out. Perhaps attempt to surgically excise the leadership of Hamas (as Israel did with Palestinian terrorist groups like Black September after the 1972 Munich murders of Israeli Olympians). In this scenario, keeping the 300,000 or so conscripts that have been called back to rejoin their military units becomes an expensive proposition.

This option is “by far the least worst for Gaza’s civilian population and for the rest of the world,” to quote Gave, and it’s plain that US diplomacy is directed toward such an outcome, with President Joe Biden now planning to visit Israel. Can Israel really show this much restraint? Its call to evacuate northern Gaza suggests otherwise. But Gave points out that this is the option that markets appear to be pricing.

A broader historical point is that the obvious comparison, the oil embargo that followed the Yom Kippur War of 1973, will almost certainly not be repeated. The world is less dependent on oil in general, while the US has greater domestic supplies to fall back on.

Aditya Singhal, head of Central Europe, Middle East and Africa trading at Deutsche Bank AG, similarly makes a strong argument that the market has this right. His two key points are:

- People believe that Hezbollah and Iran will become involved — this is wrong.

- It is very clear that Biden wants a deal to keep oil prices low.

His argument is that an Israeli ground operation will inevitably have severe human costs in terms of food and shelter, and that this will lead to pressure to desist or find a compromise. Further, none of the most important parties — including the US, China and Saudi Arabia — has an interest in a sharply increased oil price. The game theory of the event, therefore, suggests tight limits to how far this could escalate, as it’s not in anyone’s interests.

Markets Are Understating This

Tina Fordham of Fordham Global Foresight, formerly a long-time strategist for Citigroup, commented that those confident that both Israel and Iran could be persuaded to relent implied that “investors must believe faithfully in the power of American diplomacy.” While it’s in US interests to stop the conflict from spreading, the incentives on others, particularly Iran and its allies who badly want to avert any kind of peace deal between Israel and Saudi Arabia, are less clear. She said: “They must think that the presence of two US combat groups off the coast of Israel is enough to deter Hezbollah and others from escalating.”

She also suggested that the decline in the Pax Americana (in which US aircraft carriers, like “gunboat diplomacy” in an earlier era, were supposed to keep the peace), would continue to ratchet up geopolitical risks in ways that investors would have to incorporate. She pointed out that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and Azerbaijan’s move to remove the Armenian population from the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh, could be seen as a part of the same broad pattern. “Geopolitical risk is a cycle. This is a great time for someone with a grudge to try to take a bite out of someone else’s territory. You’re going to see a lot more of this.”

BCA Research’s Matt Gertken offers a set of probabilities that incorporates the US election, as American diplomats will be desperate to thwart an Israeli move against Iran before then. His odds are as follows:

- Israel’s retaliation against Hamas in Gaza will not resolve its outstanding strategic problems. The retaliation has a 70% chance of expanding beyond Gaza… over the coming 12 months.

- The highest probability outcome (45%) is that the war expands to include Hezbollah and other militant groups in Lebanon and Syria.

- The US will probably succeed in restraining Israel from attacking Iran before the US election. We see 25% odds of direct Israel-Iran conflict. That is not truly low odds but it is not our base case.

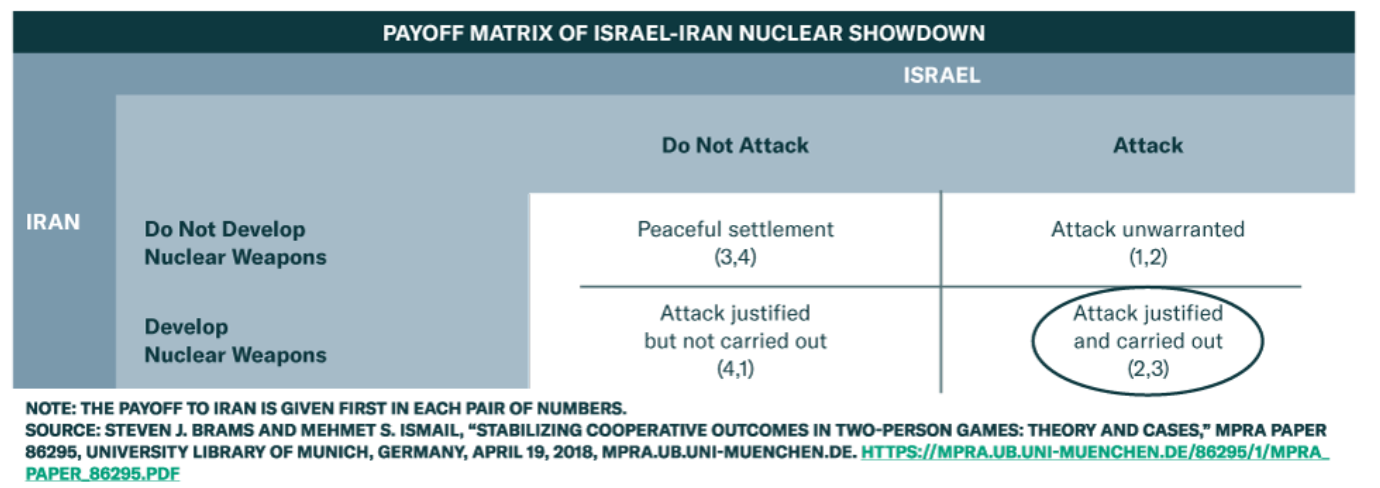

Escalating conflicts like this would be damaging for economies worldwide by forcing up the price of oil, and by snarling global supply chains once again. If the chances of a direct war between Israel and Iran are as high as one in four, that would certainly imply that markets are not yet adequately discounting the risk. This decision tree shows BCA Research’s reasoning — while a peaceful settlement might be the best possible outcome, Iran is better off developing nuclear weapons whether or not Israel attacks, while the outcome for Israel if it makes an unwarranted attack is superior to its worst scenario of failing to attack and allowing Iran to build a nuclear deterrent:

Such risks are potentially calamitous; but it’s difficult to put a cost or a probability on them, and therefore hard to incorporate into market prices. The most alarming possibility is that the Israel-Gaza showdown, perhaps in conjunction with the Russia-Ukraine war, ends up escalating to a full-blown military conflict between the US and China. Ray Dalio, the founder of Bridgewater, offers this baleful assessment:

In my opinion, this war has a high risk of leading to several other conflicts of different types in a number of places, and it is likely to have harmful effects that will extend beyond those in Israel and Gaza. Primarily for those reasons, it appears to me that the odds of transitioning from the contained conflicts to a more uncontained hot world war that includes the major powers have risen from about 35% to about 50% over the last two years.

Many dominoes need to fall before such an outcome happens, but Dalio urges everyone to read up on the history of the last two years before the outbreaks of World War I and World War II as an example of what might unfold. “What is happening now sure looks a lot like that.” He accepts that the progression to a war between the US and China “has not yet crossed the irreversible line from being containable (which it is now) to becoming a brutal war between the biggest powers and their allies.”

The greatest nightmare scenarios would be unavoidable for everyone. The readthroughs are to examine exactly how much confidence investors should be placing in US diplomacy, and to look at some risk-off assets. Even if the worst never happens, any deterioration in the international situation from here would weigh heavily on risk assets