Uddrag fra Authers:

Manic Monday |

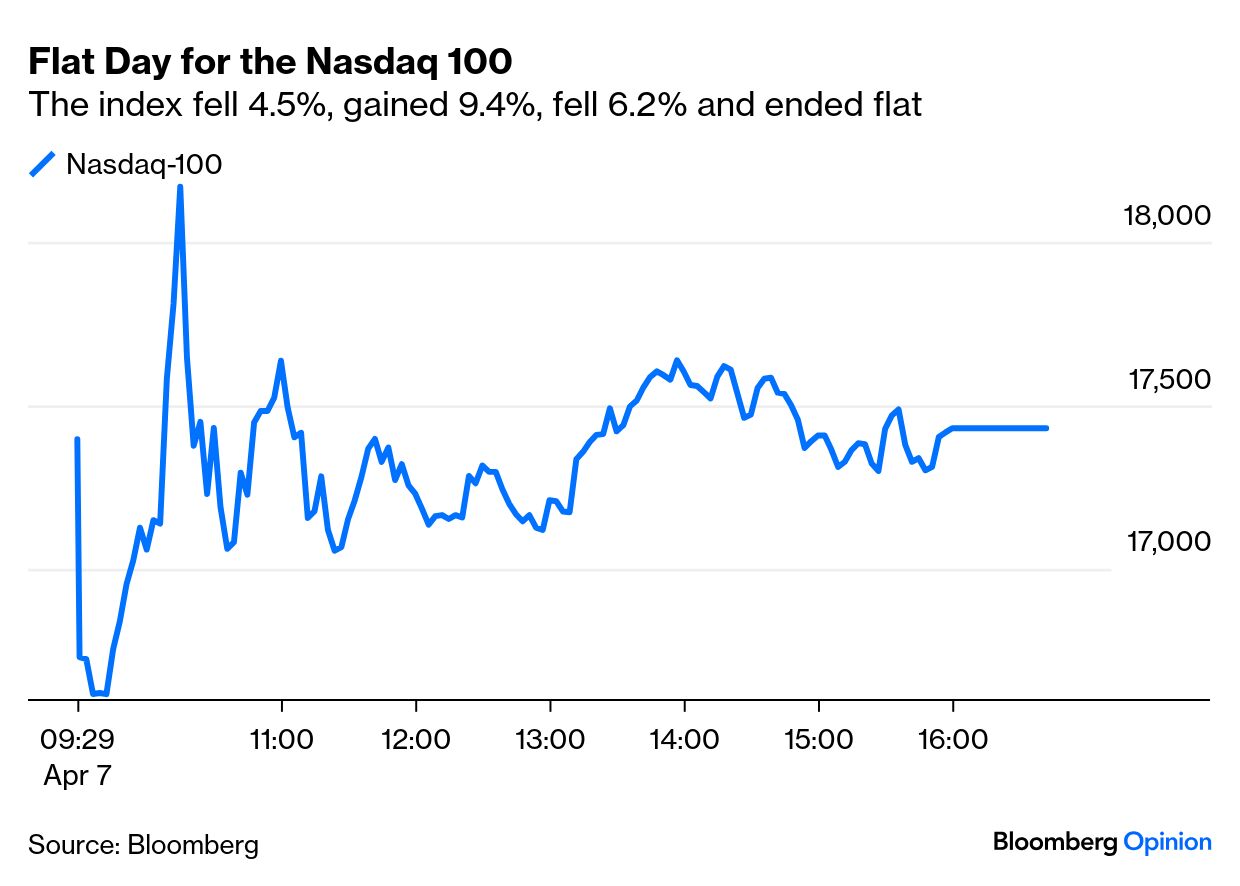

Call it Manic Monday. The US stock market started with another vertiginous crash, with the Nasdaq 100 dropping 4.5% at the open. Then it surged 9.4% on a story the White House swiftly denied that the administration was seriously considering a delay to tariffs to allow for negotiations. Then it fell 6.2%. That was all in the first hour of trading. The index ended the day up a mere 0.2%:

Volatility like this is not normal. By my calculations, the major US indexes haven’t traded in such a wide percentage range in one day since 2015. Nothing as extreme as this happened during the Covid selloff.

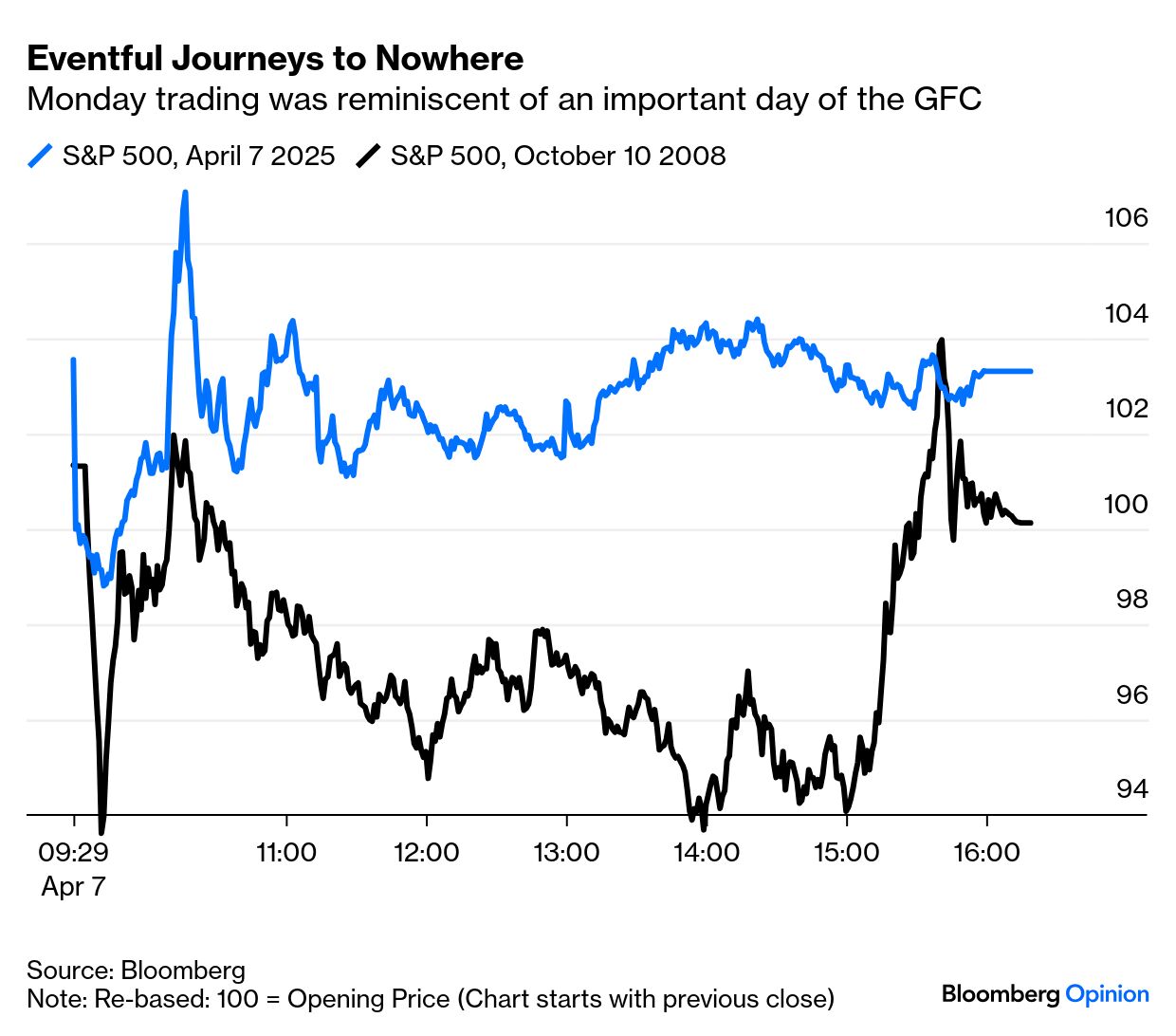

However, looking for parallels, there is one that’s encouraging. The only day I can remember that was anything seriously like this was Oct. 10, 2008. Here’s what happened to the S&P 500 then, compared to Manic Monday:

As it happens, I recorded a video at the end of that ridiculous day in 2008: here it is. I look exhausted and stunned because I was, but at least I was 17 years younger. As the video explains, Oct. 10 came a month after Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy. Market losses were limited for three weeks. Capitulation came in the week of Oct. 6-10, culminating in an extraordinarily volatile Friday that ended with indexes flat.

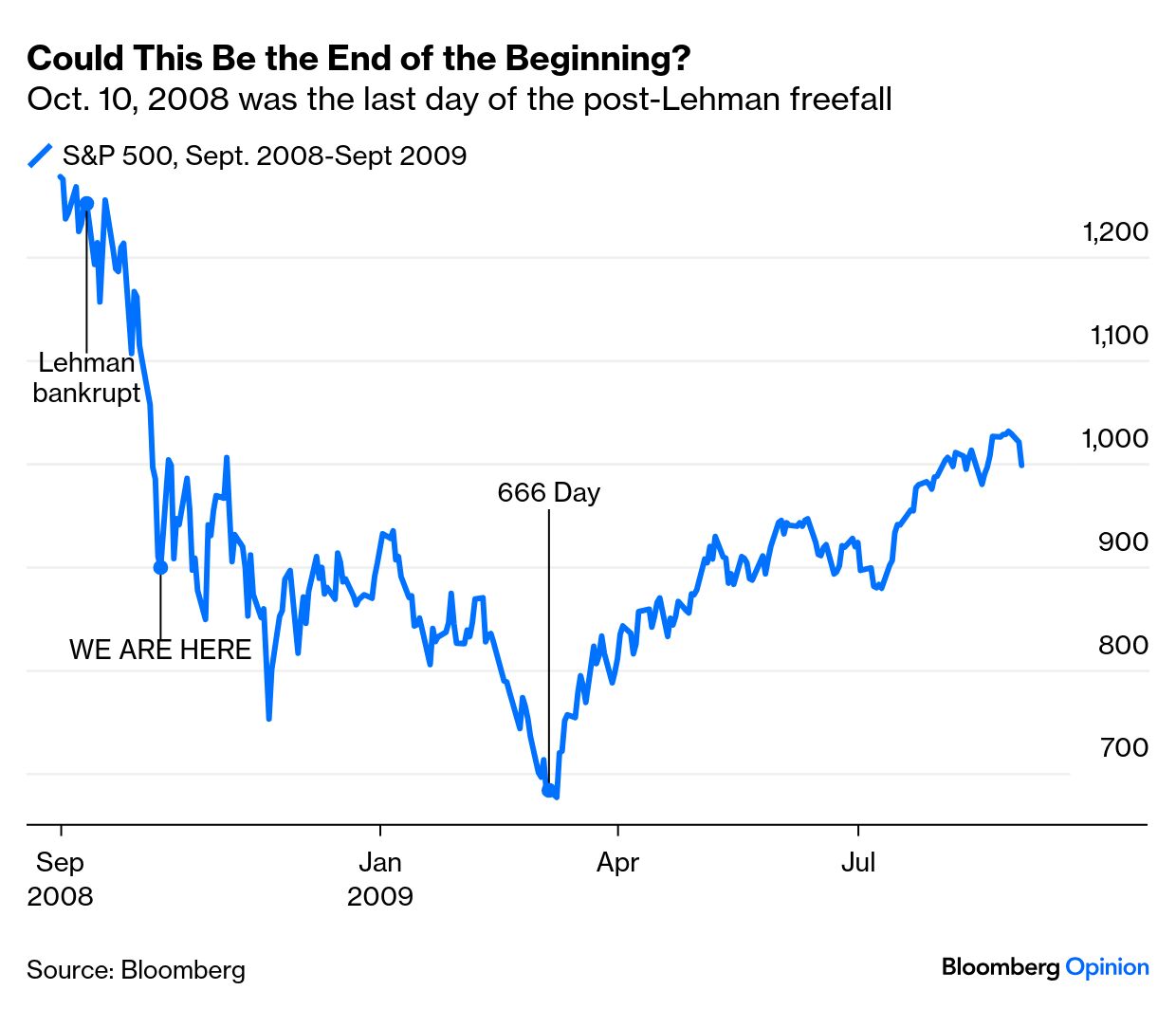

The key point for now is that that day of extreme volatility proved to end the first vertical Wile E. Coyote-style wave of selling. This is that manic Friday in context:

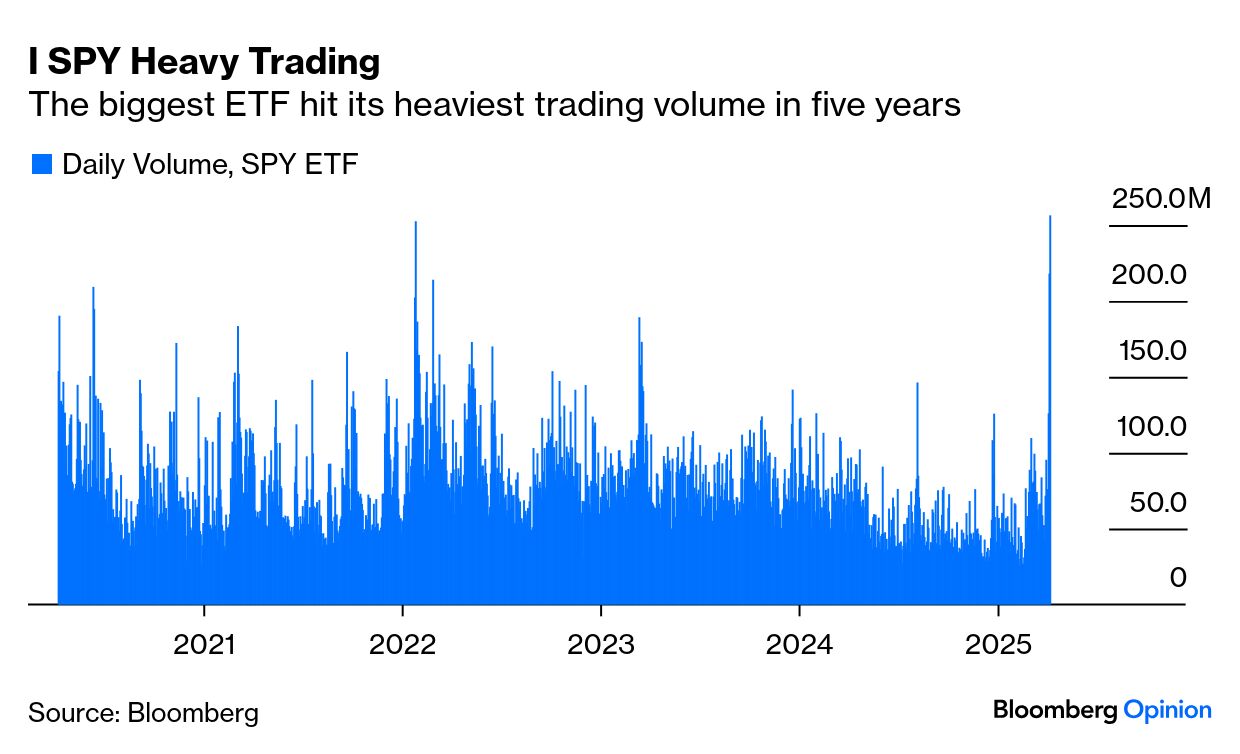

This doesn’t necessarily give evidence that we’ve hit a bottom. After such a fall, it generally takes markets a while to find a level, and the low was a full five months later. But the period of precipitous falls was over; that bizarre day was the end of the beginning. Trading volume also suggests that the initial post-Liberation Day has come to a climax. More shares in the biggest exchange-traded fund tracking the S&P 500 changed hands than on any day since Covid five years ago:

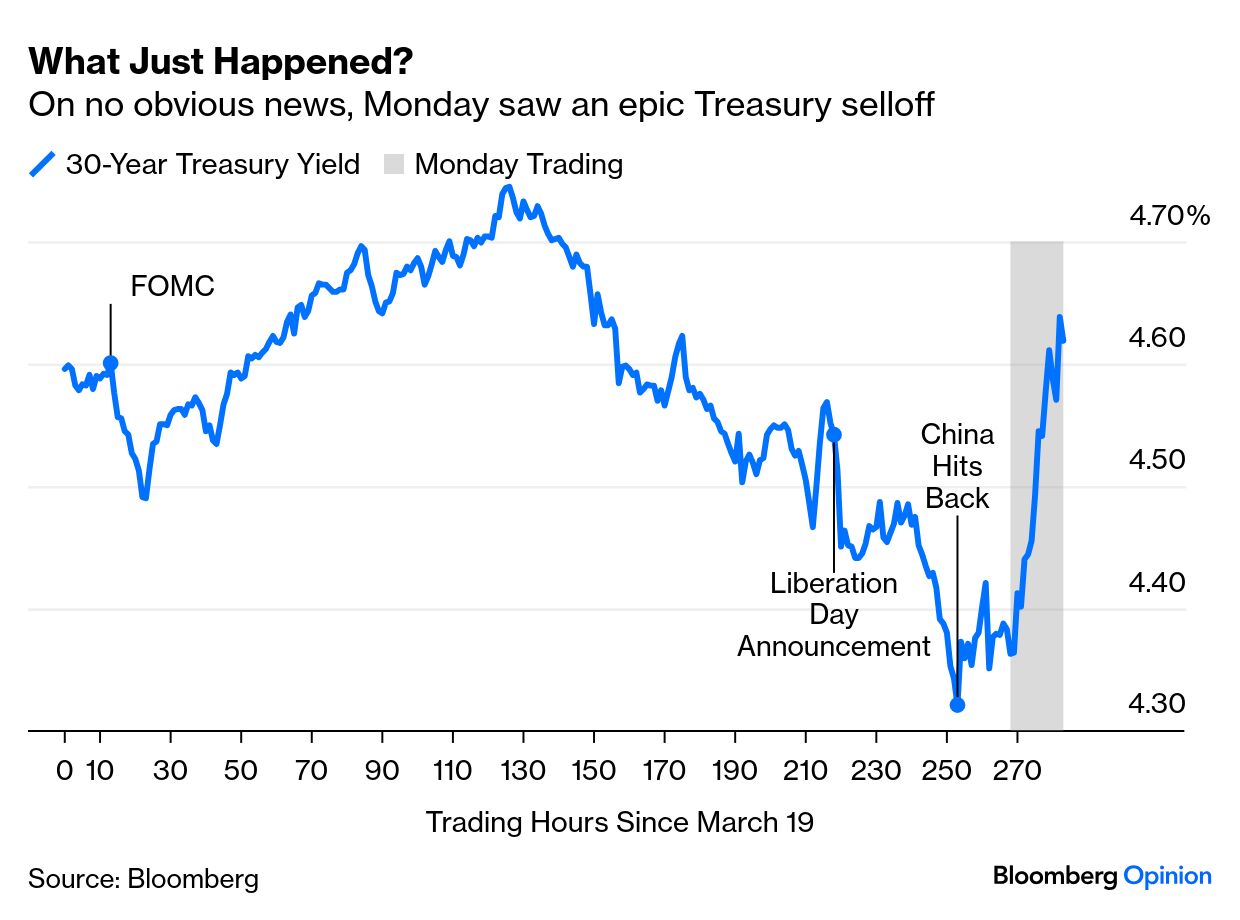

If there is reason for concern, it stemmed from the bond market, which suffered an epic selloff. As the dollar gained a little, it’s unlikely that it was foreigners who were selling Treasuries. And as the stock market was directionless amid the drama, it’s hard to believe that asset allocators exited bonds to put money there. This is how the 30-year Treasury yield has moved since last month’s Federal Open Market Committee stoked hopes for rate cuts:

This was the biggest daily Treasury selloff since Covid. The 30-year yield has only risen this much in a day six times since 2010 — and all of this when risk is perceived to be extreme. What on earth happened?

A logical but alarming explanation is that someone somewhere had to make forced sales to raise cash. If there is one alarming scenario that recurs, it’s of a contemporary LTCM meltdown — a repetition of the extreme market pain that resulted when the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund ran into trouble in the wake of the 1998 Russian debt default. That incident only ended with a rescue coordinated by the Fed and then an emergency rate cut.

Ever since LTCM, every market selloff has brought with it fears that some big institution will hit trouble and cause cascading sales. It’s logical to worry about that now. Particular concern attaches to the multi-strategy hedge fund groups that operate several different investment teams — “pod shops” in the Wall Street lingo. As the dust settles on an extraordinary day, traders will be most concerned for the health of the pod shops in their midst.