Via Charles Gave via Evergreen Gavekal blog,

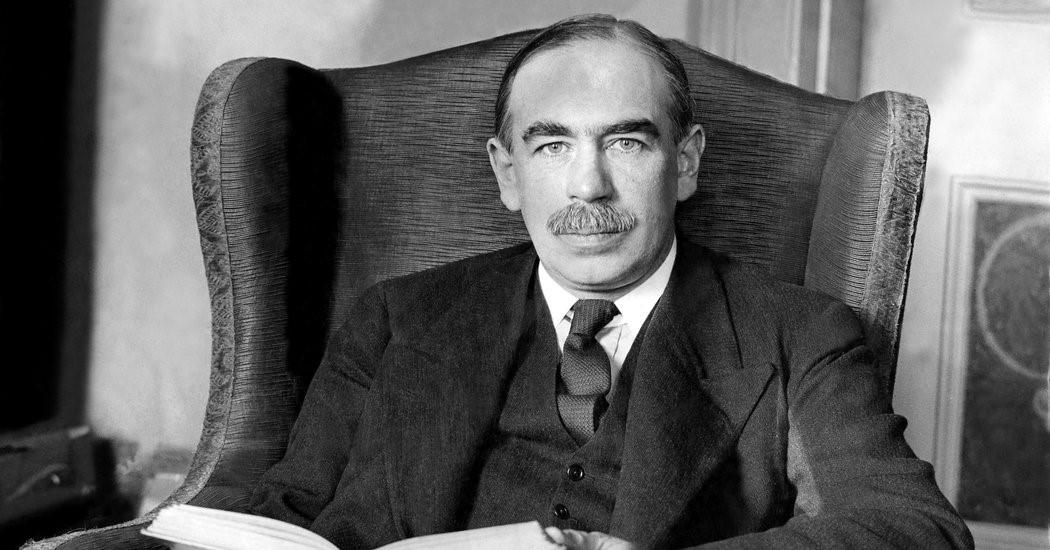

“In the long run, we are all dead.”

–JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES

INTRODUCTION

John Maynard Keynes, an English economist and author, has been held in high esteem for several decades thanks to his groundbreaking work in economics in the early 20th century. The theory he popularized in an attempt to better understand the Great Depression, aptly named Keynesian theory, revolutionized demand-side economic policy at the time.

For those who haven’t studied the riveting subject of macroeconomics since college – sarcasm, of course, for everyone out there that doesn’t live and breathe the subject like we do – Keynes advocated for increased government spending and lower taxes to stimulate economy activity, especially during times of economic hardship. Subsequently, long after his death, Keynes’ disciples proposed that optimal economic performance could be achieved through frequent “fine-tuning” by government monetary and fiscal policies (i.e. interest rates, relative to the former, and taxes/spending in the case of the latter).

Consequently, like so many well-intentioned policy initiatives meant to cope with emergency conditions, Keynes’ prescription has morphed into constant application even during mild cyclical downturns.Moreover, the other part of his master plan—to run surpluses during good times–has been almost totally ignored by election-driven politicians (are there any other kind?).

In the case of the global monetary mandarins following the financial crisis of 2007-2008, the slightest market turbulence or economic hiccup has caused them to resort to Keynesian remedies that were once reserved for true crises. As noted in prior EVAs, the net effect is a global addiction to stimulus, especially to ultra-low interest rate policies (ULIPs). But more on that in the next installment of Bubble 3.0…

As this week’s missive from Charles Gave puts forth, the question facing investors is whether Keynesian economics is dead after years being used and abused. The sorry growth record of countries which for years, if not decades, have resorted to levels of stimulus that would have made Keynes blush, indicates that its effectiveness has diminished—if not vanished. Moreover, it increasingly appears that these desperate measures have done more harm than good. In other words, it seems that a chronic overreliance on short-term, feel-good medications has led to a serious long-lasting disease. The question is particularly relevant in the European Union (EU), where interest rates have plummeted over the last 10 years to near zero, or even below. This has made it nearly impossible to stimulate a significant return on capital in the midst of a slowing economy with shrinking savings and rising debt levels. Sound at all familiar to you?

KEYNES IS DEAD; THIS IS THE LONG RUN

Yogi Berra once said that “in theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is”. Take cutting interest rates as an example. According to (Keynesian) theory, reducing interest rates is a way to borrow from future demand in order to prevent a recession today. That’s the theory, and the theory is sound. But then comes the practice, and in Europe today, we are in practice up to our necks.

When interest rates reach zero, or even worse linger in negative territory, it is safe to assume there is no more future demand left that can be brought forward to today. So, after a while, if you want to keep consuming beyond your production, the only solution is to use past savings.

For example, in Germany long rates have fallen from 4.5% in 2007 to 0.3% today. Now imagine a German pension fund (or insurance company) portfolio, fully invested (for the sake of argument) in German bunds. Further, imagine that 10% of the portfolio matures every year. Finally, imagine that this pension fund needs to pay out 3% of its value every year in pension benefits.

Between 2007 and 2011, the yield on bunds hovered around 3%, so our pension fund didn’t face a problem. The bund yield was roughly equal to the distribution rate, ensuring that the pension fund could pay its pensioners from its coupons. However, since Mario Draghi’s 2012 “whatever it takes”’ speech, yields on bunds have collapsed and now hover around 0.3%. For our hypothetical German pension fund, its income from bond coupons (0.3%) is now no longer sufficient to cover the annual pay-out to its pensioners (3%).

This means it has to sell bonds. Logically, the first bonds to get the chop will be the higher-coupon bonds bought a long time ago, because those are the bonds on which the fund has made the greatest capital gains. But selling these means the fund will receive lower average coupons in the future. And of course, the proceeds of maturing bonds and any new inflows will be invested in newly-issued bonds with a much lower yield.

Eventually, the pension fund will run out of older bonds to sell, and the only solution will be to either a) start paying pensions out of its capital, or b) to reduce its pension payouts massively.

At the risk of flogging a dead horse: when interest rates reach zero, after a while capital gains disappear, and the only way to maintain consumption is to start consuming the system’s existing stock of savings. At this point, pensioners stop living off the return on their capital, and start living on the return of their capital.

Take France as an example: one of the triggers behind the Gilet Jaune protests was the French government’s decision to stop the indexation of pensions to the French inflation rate. Could this highly unpopular decision have been made necessary by the fact that pension funds had reached the point at which the distribution of capital, rather than the distribution of returns, had started?

The low interest rate environment means that the stock of French savings is currently insufficient to provide adequate returns to retirees. So, to maintain French pensioners’ purchasing power, the only other option for the French government would have been to raise taxes on working people. But at this point in France, higher taxes are both politically and economically impossible (France is not only world champion in soccer, but also in direct and indirect taxation).

To put it simply, once the “euthanasia of the rentier” has been achieved, Keynesian policies stop working. As a result, the question confronting investors is whether Keynes is dead, and whether they are now stuck in the long run; a long run where bringing forward tomorrow’s consumption to today is no longer an option. If so, then it seems obvious that the final victims of the euro experiment will be the pensioners of Northern Europe.

Perhaps we are getting close to this point, given the current buzz in policy circles around a new way to monetize this shortfall in savings. Of course, a cynic might observe that there is nothing new about having central banks print money to make up savings shortfalls. However, in this case our cynic would be wrong. There is something new this time: a new name! Specifically, printing money for governments to spend, even when savings don’t allow for such spending, is now called Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT.

Of course, the name is something of an oxymoron; there is really nothing modern about this monetary theory. Confusing money creation with wealth creation was at the core of the debate between John Law and Richard Cantillon 300 years ago. For Law (a Scot who fled British justice, took refuge in France, and within a few years managed to drive what was then the leading economic power of the day into near bankruptcy), increases in the supply of money would lead to the employment of unused land and labor, which in turn would lead to higher productivity. Meanwhile, Cantillon explained in his Essay On Commerce that mistaking money for wealth always leads to disaster. Plus ça change...