Uddrag fra Goldman:

But in practical terms, the ruling may have a far smaller near-term impact than headlines suggest, as today’s decision only strikes down tariffs imposed under IEEPA – leaving untouched a range of other statutory authorities the administration can use to impose substantially similar trade barriers – potentially within days.

So while the Court invalidated the legal theory underpinning Trump’s broad “reciprocal” tariff framework, it did not eliminate the President’s ability to impose tariffs through other means. With a rapid policy pivot, the administration could keep much of its tariff regime in place while litigation over refunds drags on for months or years.

The Fastest Replacement: Section 122 (Trade Act of 1974)

As Goldman’s chief political economist Alec Phillips wrote back in November if the administration wants to move quickly – preserving the economic impact of tariffs while complying with the Court’s ruling – Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 offers the most immediate path.

Section 122 allows the President to impose tariffs of up to 15% for up to 150 days in response to serious balance-of-payments deficits or currency instability. Critically, this authority does not require a lengthy investigation or agency finding, meaning replacement tariffs could be announced within days.

That makes Section 122 an ideal stopgap measure: a temporary tariff floor that maintains pressure on imports while the administration launches more durable tariff actions under other statutes.

Two constraints apply:

- A 15% cap on duties

- A 150-day limit, unless Congress acts to extend the measure

But as a bridge to longer-lasting trade remedies, Section 122 offers a fast and legally distinct substitute for the invalidated IEEPA tariffs.

The Durable Workhorse: Section 301

For tariffs designed to last beyond a few months, the administration’s most likely tool is Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, which authorizes the U.S. Trade Representative to impose duties in response to unfair trade practices by foreign governments.

Unlike Section 122, Section 301 tariffs:

- Can exceed 15%

- May remain in place indefinitely

- Do not carry a built-in expiration date

The tradeoff is procedural: Section 301 typically requires investigations, consultations, and findings before tariffs are imposed – a process that can take several months.

In practice, the administration could sequence its response as follows:

- Immediately impose temporary tariffs under Section 122

- Launch or accelerate Section 301 investigations targeting key trading partners

- Replace temporary tariffs with longer-lasting Section 301 duties once investigations conclude

This “122-then-301” strategy would preserve near-term tariff pressure while building a legally sustainable framework for the long run.

Section 232 Expansion: National Security Tariffs

Another pathway is Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which permits tariffs on imports that threaten to impair national security.

Trump has used Section 232 in the past to impose duties on steel and aluminum. The same authority could be expanded to cover autos and auto parts, critical minerals, semiconductors and Industrial inputs.

While Section 232 actions require Commerce Department findings, they offer a politically defensible rationale — national security — and can underpin substantial tariffs once implemented.

As Brad Setser opines on X:

The Trump administration is sure to use other authorities (122 maybe, 232, 301) to raise tariffs now that the court has struck down the IEEPA tariffs.

But striking down IEEPA still matters, particularly for China/other countries that aren’t heavily hit by existing 232s

Consider the structure of Korea’s trade with the US v that of China. Korea export a ton of autos, which are still subject to the 232 auto tariff. Its steel is still subject to the 232 tariff there. & its chip exports could potentially be targeted by the semiconductor 232.

Korea thus doesn’t get a huge benefit from striking down the “reciprocal”/ IEEPA tariffs. Europe and Japan (autos, pharma, specialty steel) are in somewhat similar positions — tho of course they are thrilled to see the broad tariff rolled back.

China by contrast (largely because of other legacy trade action — dumping cases, the Trump 1 301) doesn’t export many products covered by the 232 tariffs to the United States right now (no auto exports to speak of, very limited steel, limited direct exports of chips — tho more are embedded in other products). So to the first approximation the court’s decision reduced the effective tariff on China from 30% to jsut over 10% — a big fall.

Now the Administration has an easy legal path available to raise the tariffs on China back up again. China hasn’t delivered on its “phase one” commitments, so the original Trump 1 301 case is still in play & allows more tariffs + there are other 301s USTR is ready to bring. But 301s put the focus on bad Chinese policies (they are targeted at China specifically, not the “trade deficit”) and that could be diplomatically risky ahead of the Trump-Xi summit …

So it will be interesting to see what the Administration does + how quickly it moves to return the tariff on China to ~ 30% …

The other big question will be whether to use section 122 to impose something close to an across the broad, balance of payments tariff of 15% That is clearly legal, But the tariffs are only in place for 150 days without a vote of Congress, and that vote would be dicey (just before the mid-terms … ) So it is easy for the administration to say that they will use other authorities to replicate the IEEPA/ reciprocal tariffs — but it isn’t super easy to do in practice

(and doing it through 232s would be a stretch for many consumer goods)

The “Nuclear Option”: Section 338

If Section 122 is the Band-Aid and Section 301 is the workhorse, Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930 is the equivalent of breaking the glass in case of emergency.

It would allow Trump to impose tariffs of up to 50% on imports from any country that is found to be engaging in “unreasonable” or discriminatory trade practices against U.S. commerce – and unlike more modern trade remedies, it does not require the same kind of prolonged investigative process typically associated with Section 301 or Section 232 actions. That combination – high ceilings and comparatively flexible procedural triggers – is precisely what makes Section 338 so attractive in the aftermath of the Court’s decision.

It’s also why it’s never been used.

For nearly a century, administrations from both parties have treated Section 338 as something of a legal relic: broad in theory, politically explosive in practice, and almost guaranteed to provoke retaliation or litigation the moment it’s invoked. In a post-IEEPA world where the Court has made clear that emergency sanctions law cannot double as a blank check for tariffs, Section 338 offers the closest statutory analogue to the kind of sweeping leverage the administration had been attempting to exercise under its “reciprocal tariff” framework.

Deployed aggressively, Section 338 could function as a country-level tariff escalator – allowing the White House to target major trading partners not on a product-by-product national security rationale (as with Section 232), nor on a case-specific unfair practice finding (as with Section 301), but on a broader determination that a foreign nation’s trade regime places systemic burdens on U.S. industry.

From a political standpoint, invoking Section 338 would also reframe the debate. Rather than justifying tariffs through a declared economic emergency (as with IEEPA) or supply chain vulnerabilities (as with Section 232), the administration could argue it is responding directly to foreign governments’ trade discrimination – an argument that tends to resonate more cleanly with voters.

But the legal risk would be immediate and substantial.

A Different Route: Import Licensing

Tariffs are not the only way to restrict imports.

Trade lawyers have long noted that import licensing or quota systems can create economic effects similar to tariffs without formally imposing duties. The administration could pursue licensing schemes — potentially even under IEEPA — to regulate the volume or eligibility of imports rather than taxing them directly.

“There’s another way of doing it, but it’s more cumbersome,” Trump said in late January when asked what the administration might do if they lose the tariff case. “I don’t want to scare you, but it’s more, much more cumbersome.”

Trump later noted that “you’re allowed to do a license” under the International Economic Emergency Powers Act and a “tariff is probably less severe than what a license could be.”

[A] person familiar with the administration’s thinking, who was granted anonymity to discuss the situation, said the administration has “been considering this for a long time,” both if the IEEPA tariffs are struck down and in the context of a Section 232 investigation into whether to impose tariffs or other import restrictions on polysilicon.

Developing an import licensing scheme to cover the trillions of dollars worth of goods now subject to tariffs would be “a massive undertaking for sure,” the person said. “It’s just there are certain industries where it really makes sense to do it.”

Currently, only certain goods require an import license, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The list includes cheeses, sugar, arms, ammunition, explosives, radioactive materials, biological drugs, wildlife and pets.

The Coalition for a Prosperous America, an industry group that supports the administration’s protectionist trade policy, has called for more import licensing schemes to manage trade. –Politico

Such a move would almost certainly be challenged in court if it functioned as a “tariff by another name,” but in the interim it could sustain meaningful trade restrictions.

Refunds: The multi-Billion-Dollar Question

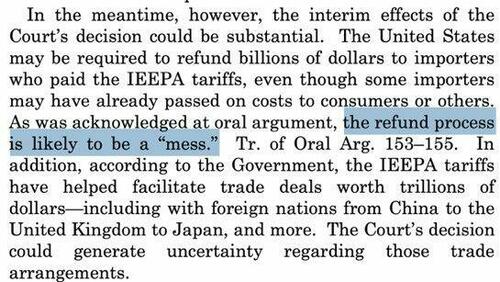

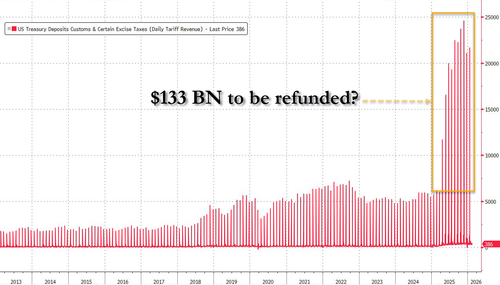

Perhaps the most immediate practical consequence of the ruling is what it does not address: the fate of tariff revenue already collected. The Court’s decision invalidates the legal basis for certain tariffs going forward but offers no guidance – just that it will be a ‘mess.’

Refunds are not automatic and may take months – or years – to resolve through administrative protests and litigation in the U.S. Court of International Trade.

Importers seeking repayment may face hurdles including:

- Sovereign immunity defenses

- Administrative exhaustion requirements

- Timely protest rules

In many cases, duties paid without formal protest may not be recoverable at all.

As Kavanaugh noted in today’s decision, refund claims are likely to become a major near-term consequence of the ruling – shifting the next phase of the dispute into trade court even as replacement tariffs are imposed under new legal authorities.