Uddrag fra Authers, FT:

The Federal Reserve is going to cut rates this week for the first time in 12 months. It will probably reduce the overnight fed funds rate by 0.25 percentage points, but there’s a chance it might still opt for a so-called “jumbo” cut of 0.5 percentage points. The increasingly ugly legal battle over whether Fed governor Lisa Cook should be allowed to vote in Wednesday’s meeting doesn’t affect this in the slightest, for all the potential long-term ramifications of replacing her.

That much is clear from last week’s US unemployment and inflation data. However, the risks that the Fed won’t cut much more, or might even have to reverse course, remain. Unemployment is rising, while inflation remains relatively controlled, and it behooves the Fed to cut for now. But much else is still murky.

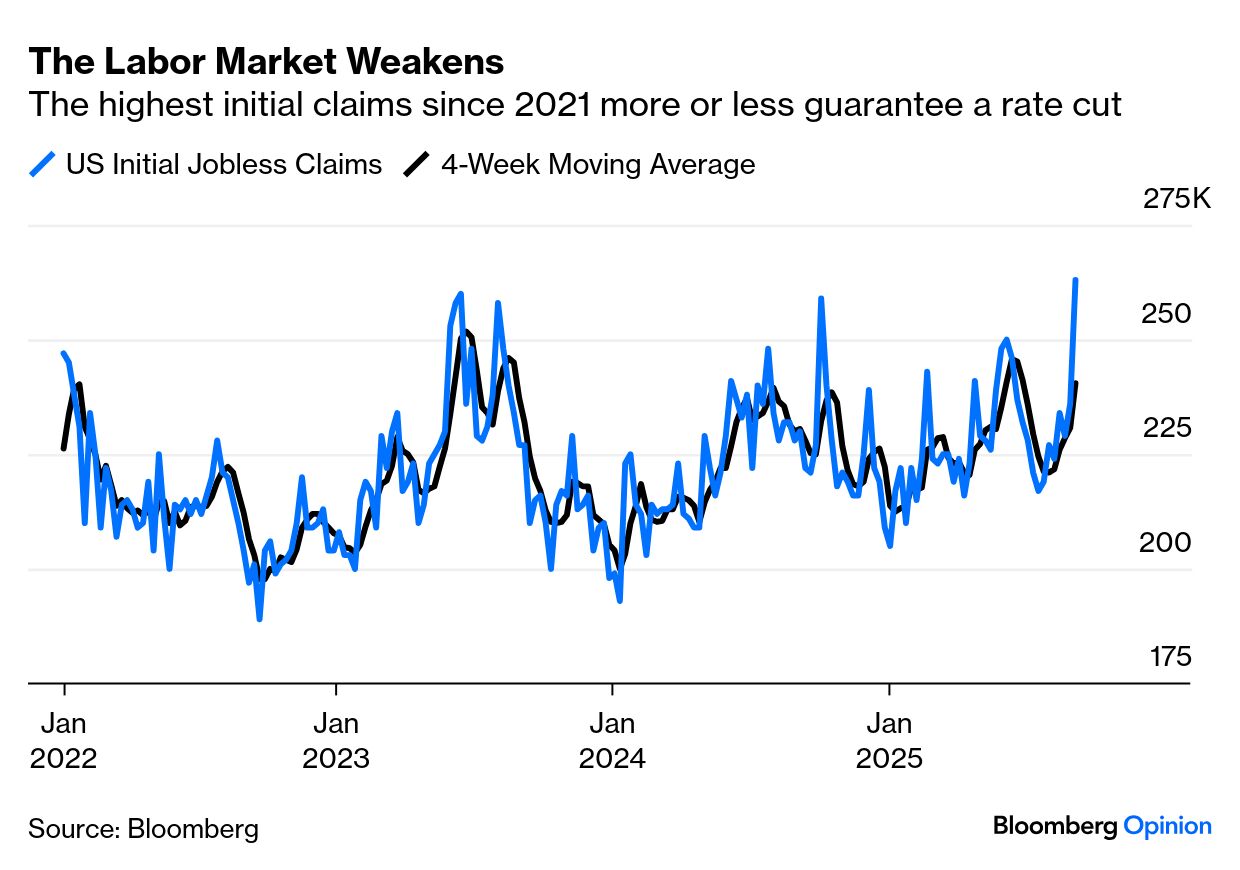

A nasty surprise from the jobless claims data, revised weekly and the closest approach to a real-time measure of the labor market, seals the case for an easing with the highest number since late in 2021. This is a noisy series, and claims over the last four weeks remain a bit lower than their recent peak, but a chart like this will plainly move a central bank that has already said it was more worried by employment than inflation:

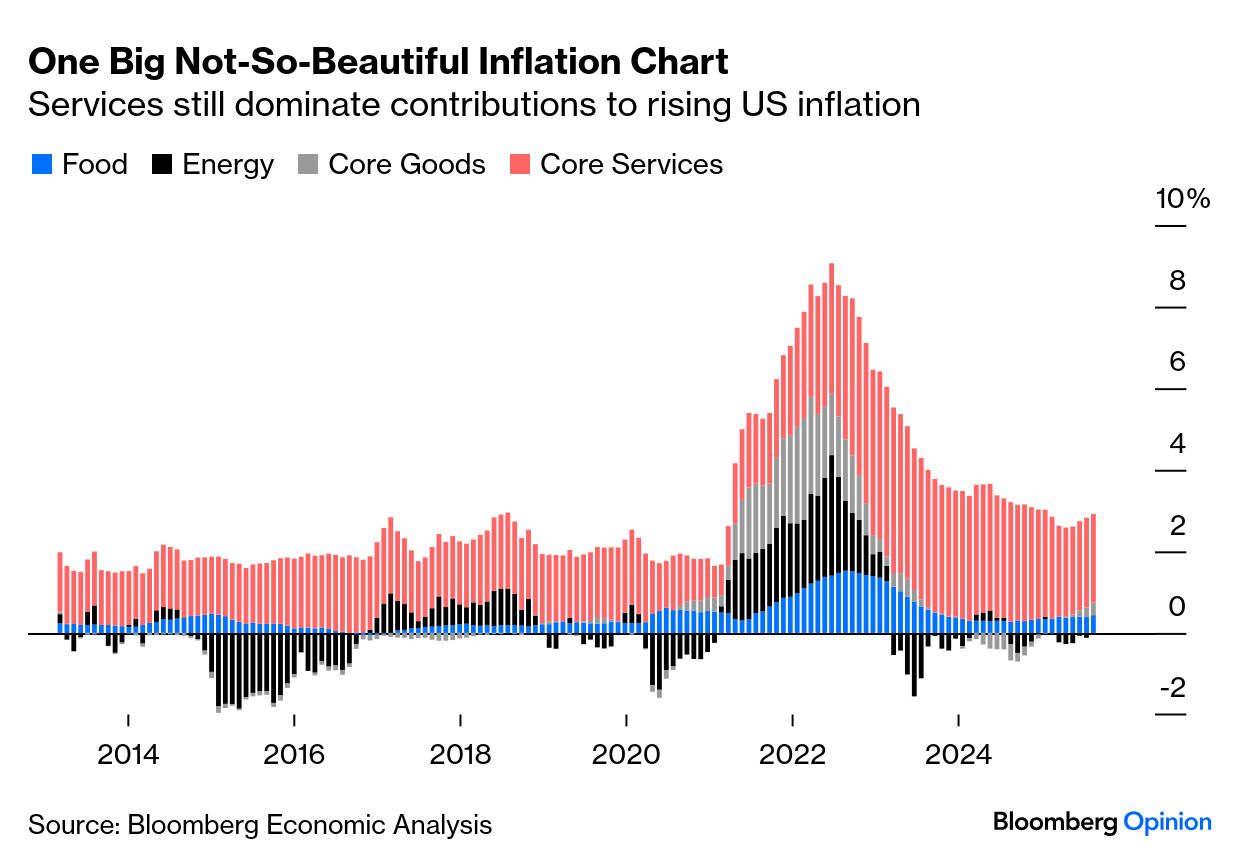

Inflation remains complex, but doesn’t give enough reason for the Fed to stay their hand. It continues to be dominated by services, as this breakdown into its four main components shows. The fall in overall price rises is over:

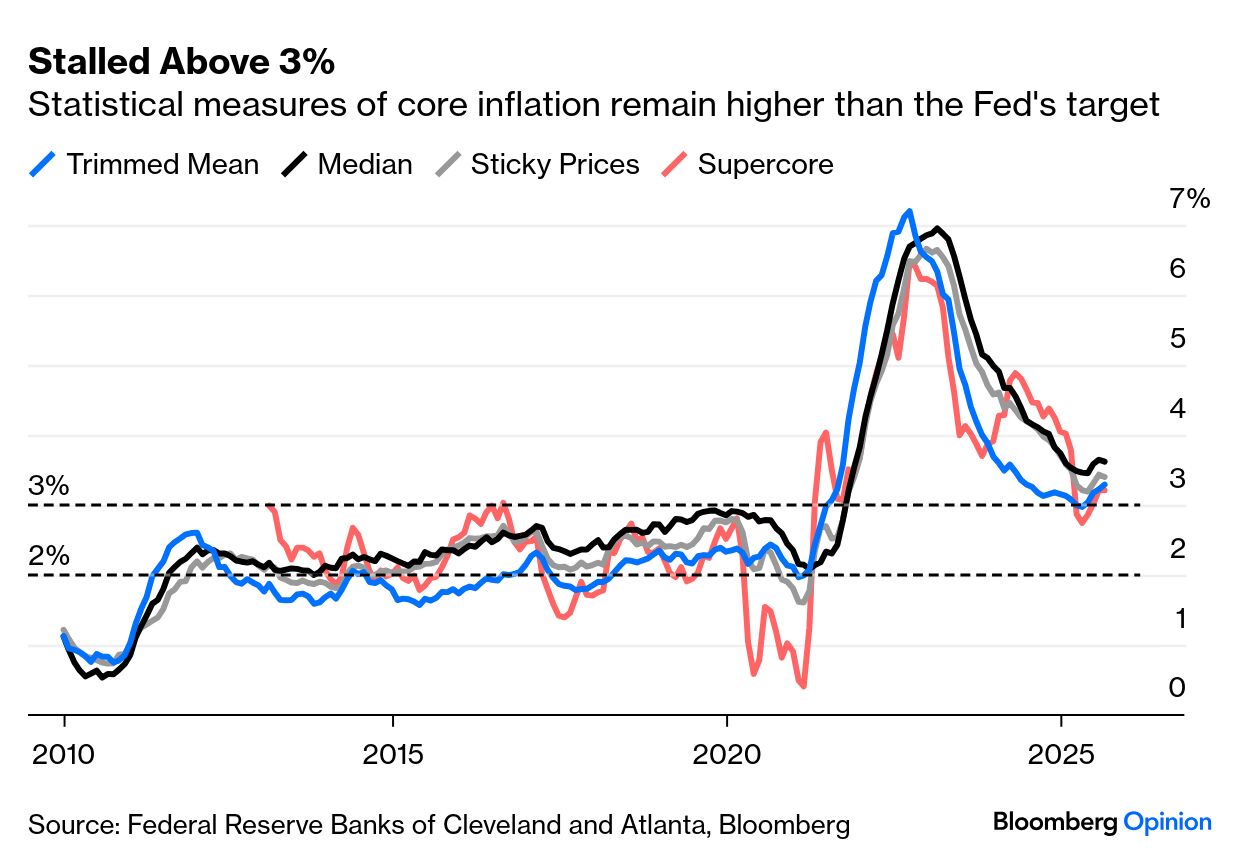

The technical statistical measures beloved by the Fed showed no great worsening, and certainly no great impact of tariffs on the overall numbers. The trimmed mean ticked up very slightly, as did the measure dubbed Supercore by the central bank (services excluding housing), while the median and the Atlanta Fed’s index of sticky prices both ticked down very slightly. All have stalled above 3%, the upper range of the Fed’s target:

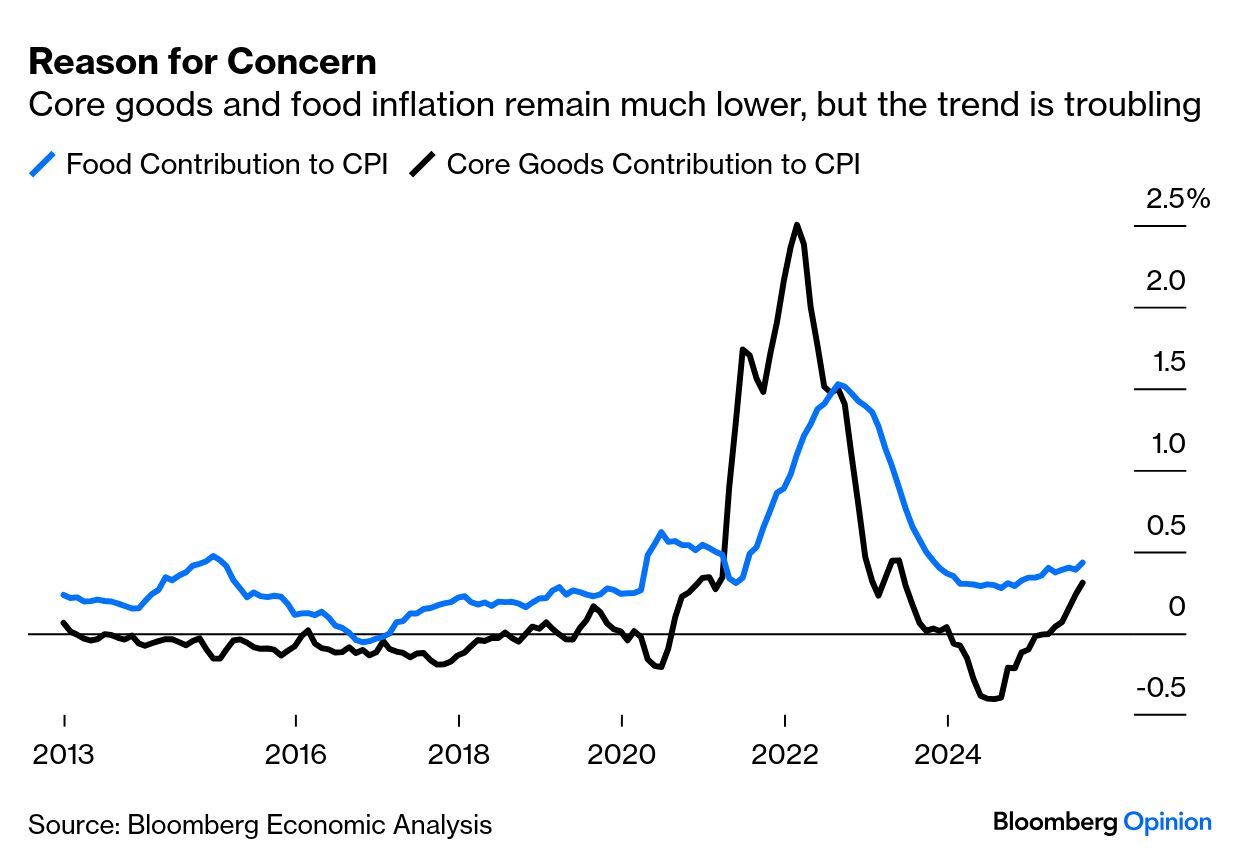

Reason for concern about tariffs comes from core goods and food, areas most directly affected by the trade levies. Neither makes much of an impact on the overall index, but the contribution of core goods is now positive and rising fast, while food prices are also adding more to the index. These are the trends to check whether the tariffs do indeed have a serious negative impact on the cost of living:

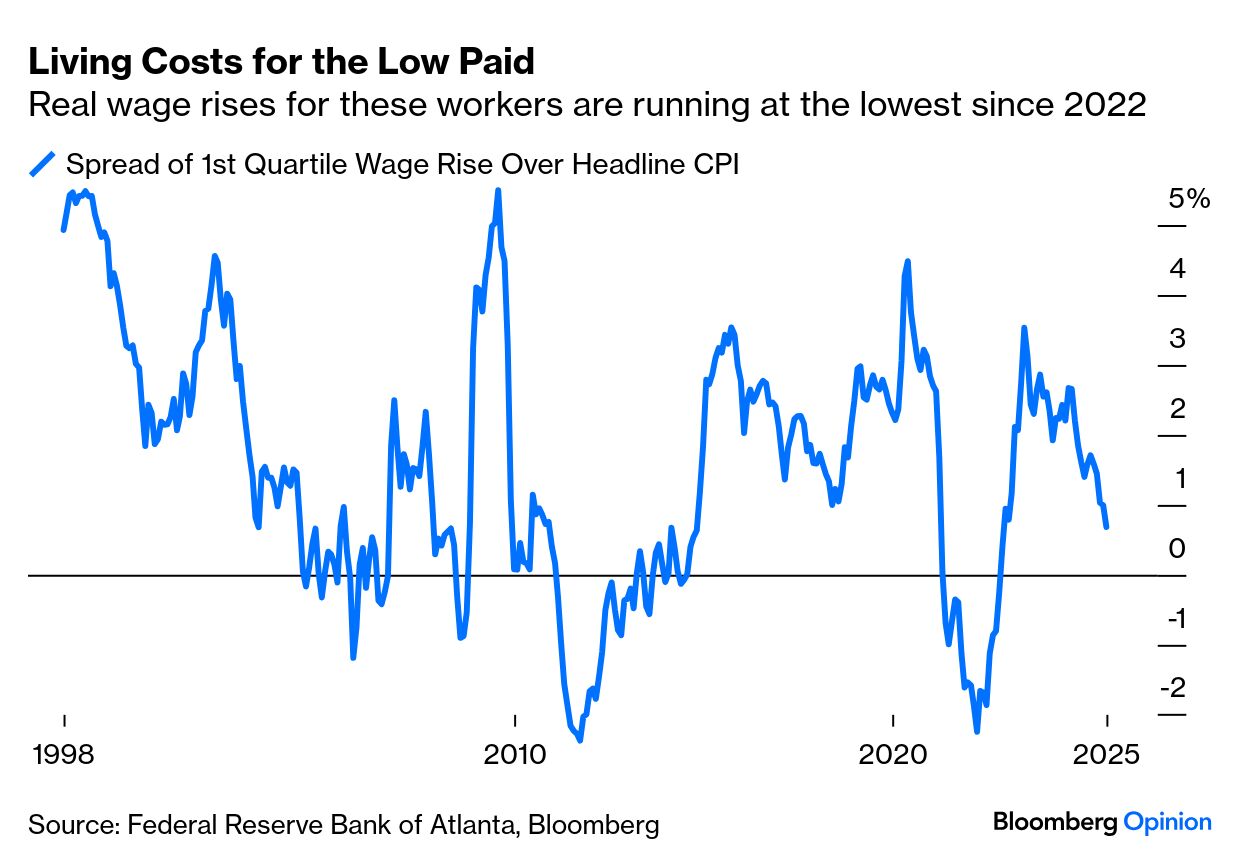

The lower paid are of particular worry, as they are crucial to President Donald Trump’s political base. The Atlanta Fed’s wage tracker, based on census data, slices and dices pay rises several ways. Wage increases for the first quartile, the 25% of the population who are paid the least, have pegged back sharply and are now only just above the headline rate of inflation. This is in line with the theory that companies are hoarding labor and reluctant to make layoffs, but have very little interest in bidding up for lower-skilled workers.

It’s not a coincidence that the two times real pay rises for the lowest paid went negative in recent history came during the administrations of Barack Obama and Joe Biden — and both times they were followed by a Trump election victory:

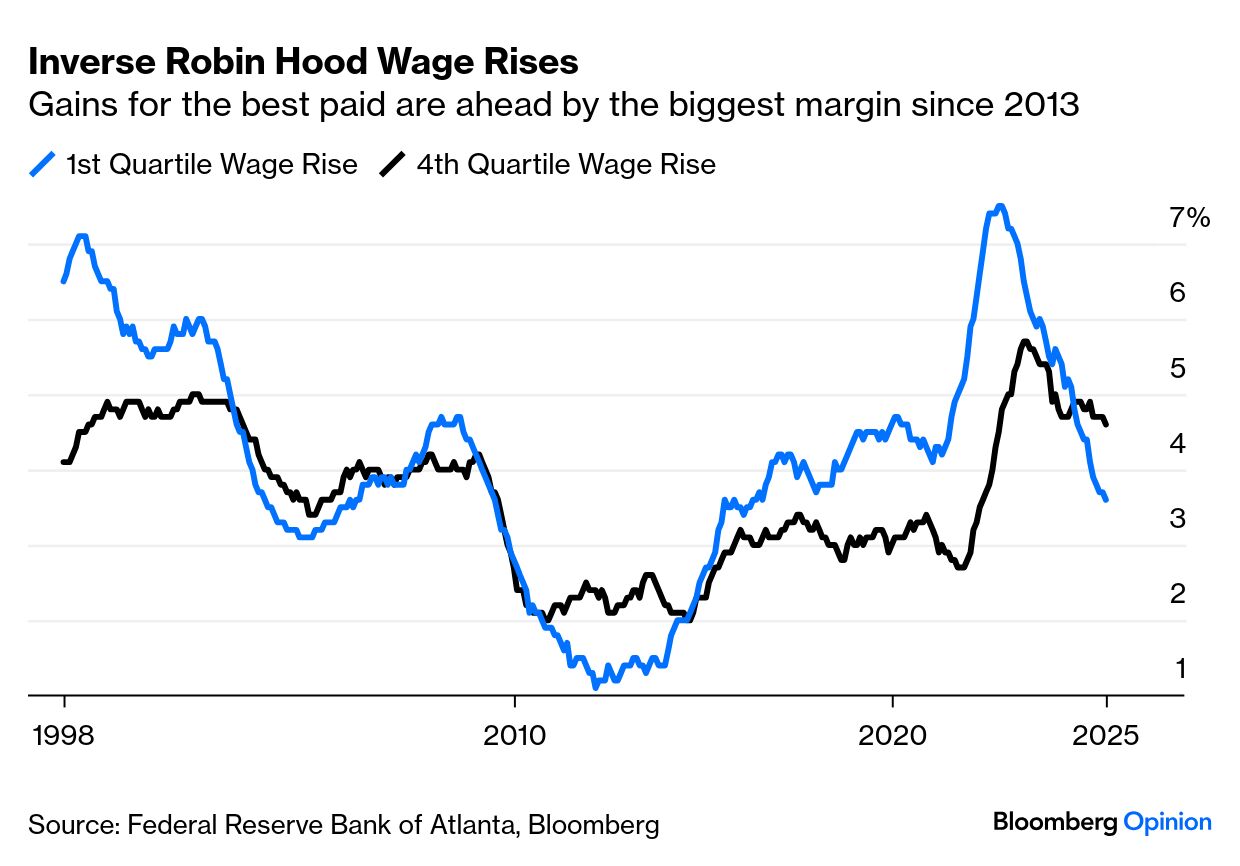

Another worrying sign for the administration lies in inequality. Usually, the lowest paid get higher percentage rises; they’re cheaper for employers. Their wages are now suddenly lagging the best remunerated to a startling extent, previously only briefly seen for a few months under Obama:

Lower rates help out indebted consumers, but tend to stoke inequality by juicing up the price of assets, generally only held by those who have money in the first place. So while the drop in wage rises for the low paid adds to the case to cut rates, it also suggests possible problems down the road.

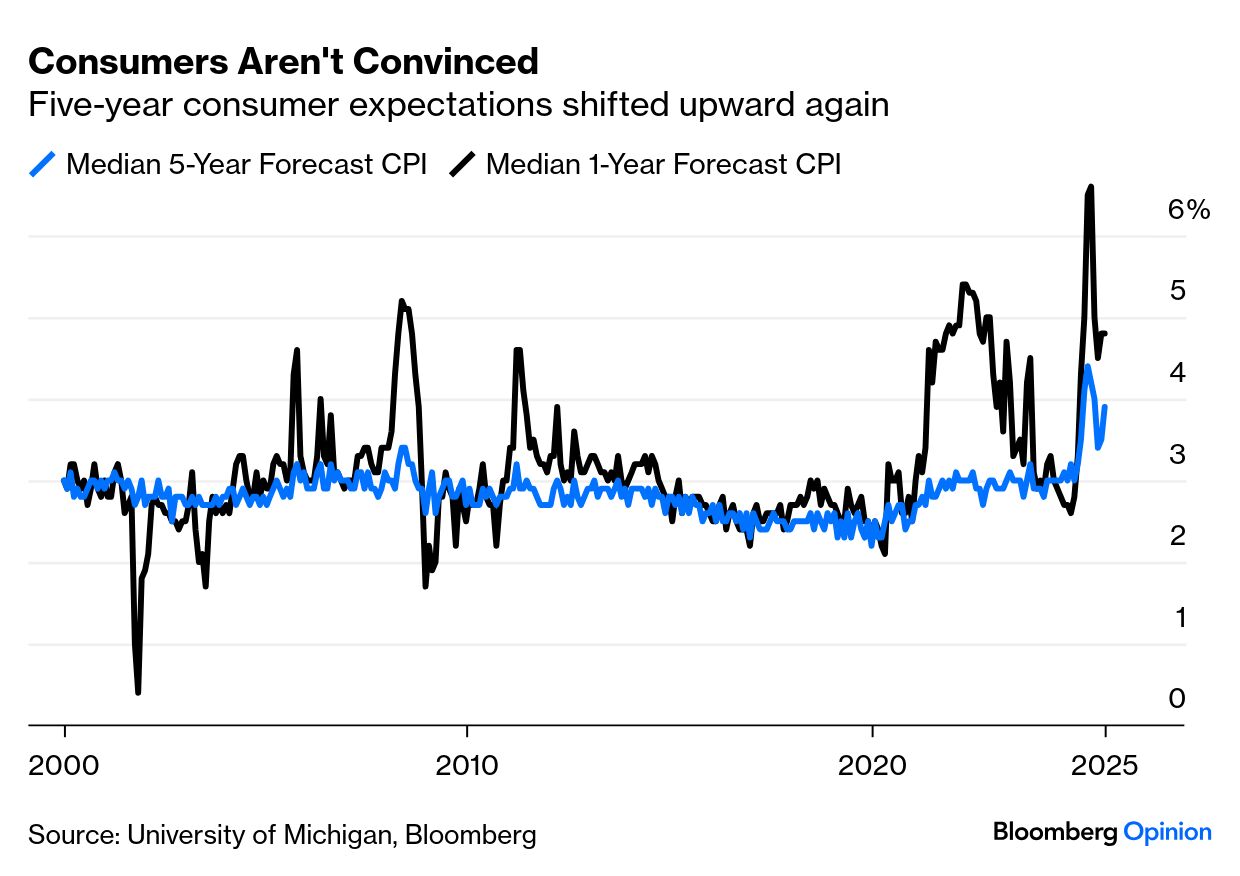

One more reason why the Fed might not want to cut rates too aggressively — inflation expectations still look unmoored. The University of Michigan’s regular consumer survey shows them moving back up last month. Particularly for the longer term, they are riding significantly higher than at any time since 2000:

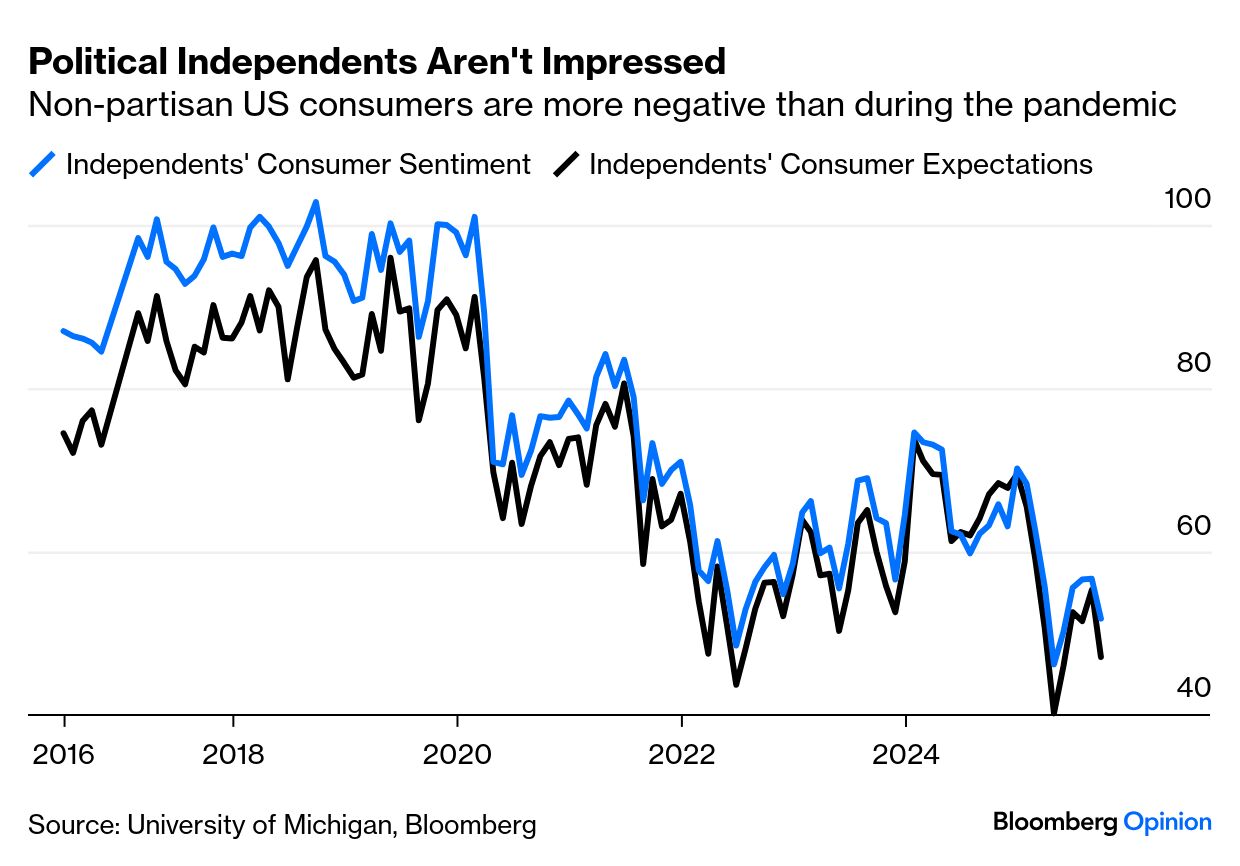

Consumer surveys are increasingly contaminated by political polarization, as people answer questions through a partisan lens; with Trump in power, Republicans think things are great and Democrats think they’re terrible. Self-identified independents offer a good way to control for this — and it’s noticeable that both in current sentiment and their expectations they are more negative than at any time during the pandemic. They remain above the post-“Liberation Day” nadir, but not by much:

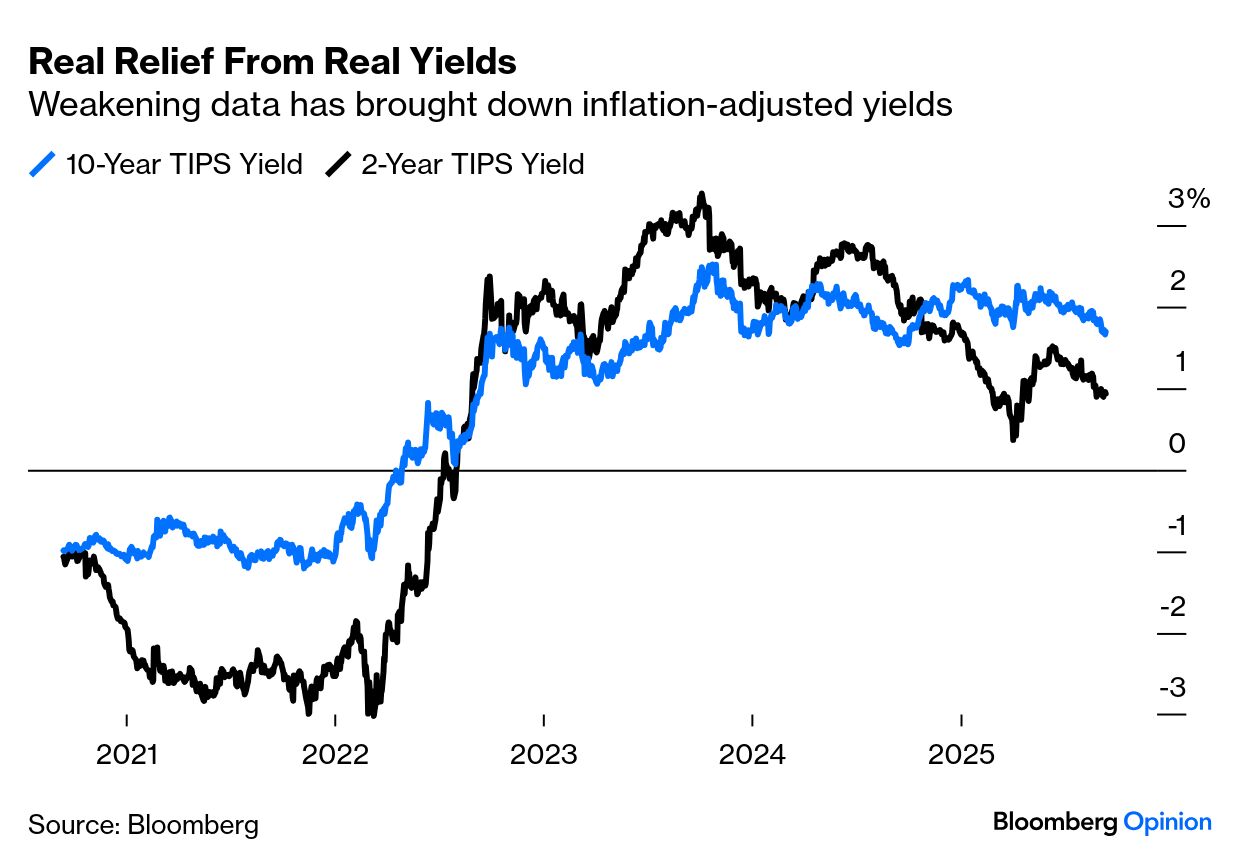

This tends to reinforce the case for a rate cut, but also suggests that conditions are too bad for equities and other risk assets to flourish. Why are investors so much more confident than consumers? The expectation of lower rates instantaneously eases conditions. Longer-dated bond yields have been rising ominously, fueled by fears that governments on both sides of the Atlantic don’t have their deficits under control. The fresh certainty that the Fed will ease has brought down real yields nicely, and that boosts risky assets:

The Fed is going to cut, and there is a strong case for it to do so. With inflation not tamed and tariffs still to filter through into employment and production decisions, the risk ahead is stagflation.