Nordea har analyseret den kraftigt stigende offentlige gæld som følge af pandemien. Den amerikanske gæld er steget kraftigt til 130 pct. af BNP, mens den tyske kun er steget svagt til 70 pct. Men staternes rentebetaling er meget små, så den voksende gæld fører ikke til en alvorlig gældsbyrde. Over 100 europæiske økonomer har foreslået, at den offentlige gæld, som ECB holder, skal skrottes. De mener, at ECB enten bør skrotte gælden eller omveksle den til evigt løbende obligagtioner til nul procent i rente.

On debt cancellations and why it has maybe already happened in practice

The “boundless” costs of the pandemic leave governments with no choice but to finance lockdowns with increasing public debts. As long as central banks hold a large part of the bond market, long bond yields can increase without huge repercussions.

Highlights:

- Reactions to the pandemic are stronger than ever: Debt-to-GDP ratios are record high and governments went damage controlling more rapidly

- The US response to the COVID crisis is five times stronger than to the financial crisis in 2008

- No need to sweat over debt: The interest rate burden has declined though debt levels have increased

- When central banks increase their share of public debt, the debt is de facto cancelled (if they intend to roll-over the purchases in the future, which is likely) as interest rate payments are returned to the governments as dividends.

- Bottom-line: Bond yields can increase from current levels (in an orderly fashion) without causing a land-slide in global public finances

Harder, better, faster, stronger

As leaders are forced to increase public obligations for the financing of lockdowns, central bankers got their back and opted for the E2-E4 move: Buy the treasuries and take a ride on the interest-carrousel.

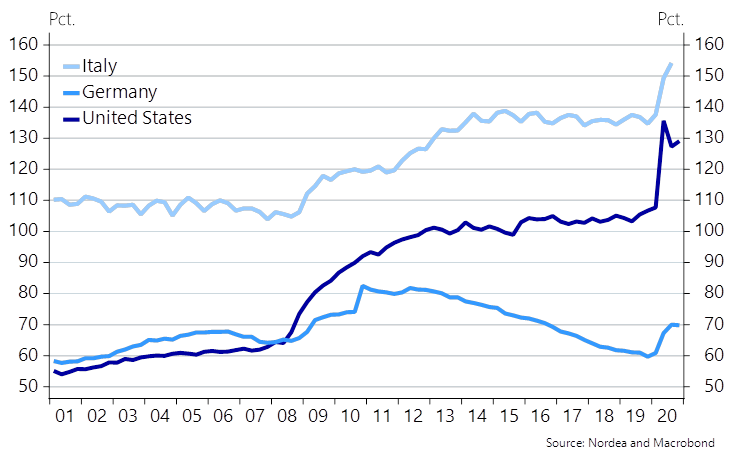

This time, however, the coordination scheme between elected officials and central bankers is better and at a larger scale than crisis reactions historically seen. The US public debt-to-GDP ratio first exceeded 100 pct. in 2012 and the largest QoQ difference before the record change of 27.9 percentage points in 2020Q2 was in reaction to the financial crisis in 2008Q4 where the debt-to-GDP ratio increased by 5.9 percentage points.

Likewise did Italy and Germany increase their public debt-to-GDP ratios by 11.7 and 6.4 percentage points in 2020Q2. Comparing historical responses, the second-largest QoQ change for Italy was 6.0 percentage points in the aftermath of the financial crisis in 2009Q1 and 8.4 percentage points for Germany in response to the European credit crisis in 2010Q4.

The German public debt-to-GDP ratio hit a nice round number of 70.0 pct. in the last quarter of 2020, lower than the peak of 82.5 pct. in the aftermath of the financial crisis, but above the Maastricht Treaty’s reference level of 60 pct. of GDP. At the same time, Italy and the US won’t go low, accumulating debt-to-GDP ratios of 154.2 and 124.9, respectively.

Chart 1: Debt-to-GDP ratios

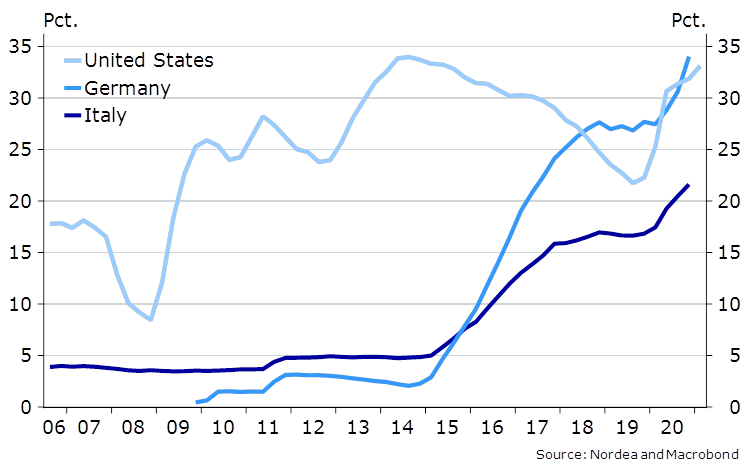

Central banks increase their share of public debts

Banca d’Italia holds 22 pct. of the Italian public debt, the Bundesbank holds 34 pct. of the German public debt, and the Fed holds 33 pct. of the American public debt, the same record high level as in 2014.

The Fed’s balance sheet now accounts for almost $8.0tr compared to $4.31tr as of March 2020. This makes QE4 the largest (and fastest) Large-Scale Asset Purchase Program. Set side by side, the first round of quantitative easing, QE1 from 2008 to early 2010, included $175bn in agency debt, $1.25tn in agency mortgage-backed securities, and $200bn in Treasuries.

QE2 and QE3 increased Fed’s balance sheet to $4.5tn with extra $600bn Treasuries, purchased with a pace of $75bn per month from late-2010 to mid-2011 under QE2, and a total of $1.6tn in MBS and Treasuries under QE3 from 2012-2014. The Fed comes prepared for battle.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the Europeans follow a slightly more hesitant rescue plan introduced by the ECB as the Pandemic Emergency Purchasing Programme (PEPP) with a total envelope of €1.850bn until at least March 2022. The program began in March 2020, where Italy was already an epicenter. The ECB concurrently continues the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) with a monthly pace of €20bn.

As with other EU programs, Eurosystem national central banks and the ECB purchase the public securities, which today aggregate to €1tn. Naturally, high debt levels and fear of inflation as society reopens lead to a fear of increasing interest rate payments, which create turmoil on markets and bring up altruistic discussions.

This current disposition is what has brought more than 100 European economists into action with the mission to cancel the public debt held by the ECB and “take back control” of our destiny. They argue that extraordinary times call upon extraordinary measures: ECB should either cancel the debts of member states or transform the debt into perpetual bonds with zero-coupon rates.

Well, doesn’t that strike a chord? The melody probably takes you back to our FAQ on MMT, where we indeed discuss the possibility of monetary fiscal funding with perpetual bonds with insignificantly low interest rates as the most likely scenario of a pilot episode of MMT in practice.

Chart 2: Debt share held by central banks

Interest rates down, debt up

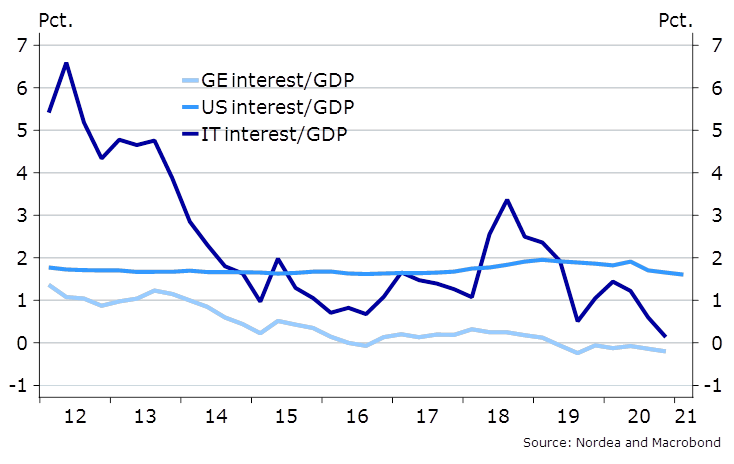

Yields have been low ever since the financial crisis, and while inflation accordingly comes in Q2, we need not necessarily worry. The interest rate payments-to-GDP will be shielded by the large holdings of government debt in QE programmes, why the increase in payments from the higher debt levels is (at least partly) offset by artificially low interest rates and positive GDP growth, eroding the otherwise increasing relationship.

One should remember that interest payments on debt owned by central banks is effectively annulled as the central bank returns dividends to the same governments. This is an effective shield against higher bond yields, since the central banks are likely to continuously buy a large proportion of the net issuance going forward.

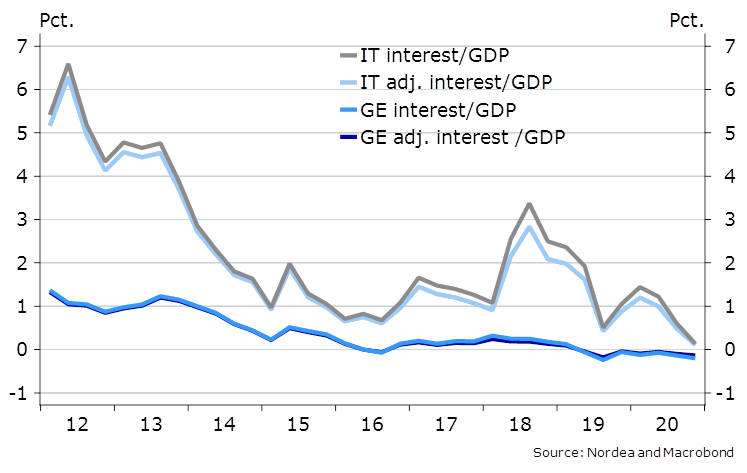

Chart 3: Interest payments on public debt to GDP (Italy proxied by a 7yr WAM)

Fear of too high debt levels has got the best of some, while others remain calm. So who should be the lead to follow?

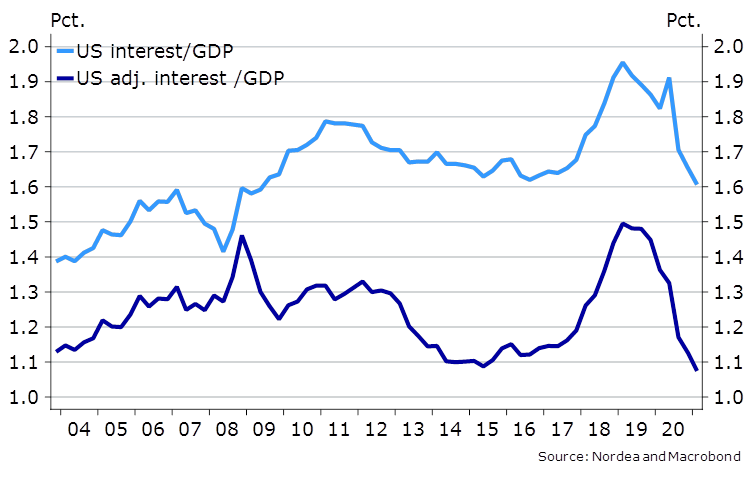

When the central bank holds government bonds, the bonds enter a circular flow of interest payments from the national government to the central bank and back to the government at the end of the fiscal year. The Fed sent $88.5 billion in profits to the US Treasury in 2020, the so-called remittances, stemming from interest income from bond holdings.

Specifically, the Fed is obliged to cover its operating costs with revenue and send resulting profit to the Treasury’s general fund to cover government expenses. Similar agreements apply to other central banks. Hence why increasing public debt might not matter that much – at least if it remains at the hands of the central bank.

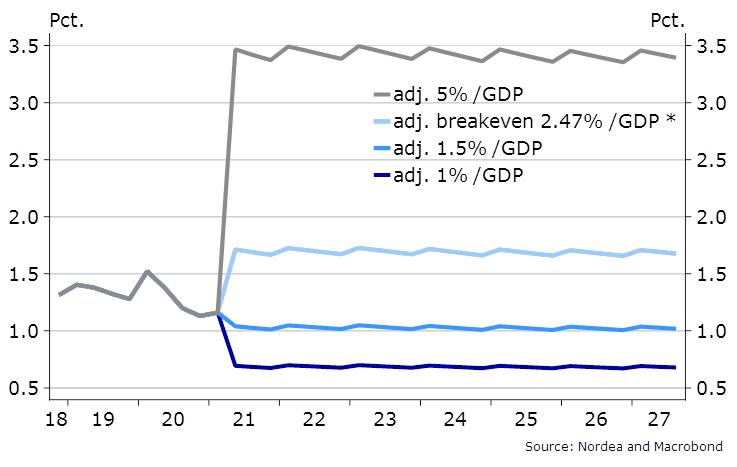

Chart 4 shows the interest rate payments on the debt, adjusted for the Fed holdings. Assuming that governments receive 96-97 pct. of interest rate payments paid to central banks as dividends at the end of the year and the remaining 3-4 pct. is lost in administrative fees, the cost of interest rate payments is almost non-existing when the Fed holds a large share of public debt.

Chart 4: US interest rate payments adjusted for the share held by the Fed

The interest rate level has less impact the larger the share of public debt the central bank holds. The winner seems to be the US government, which has taken on astonishingly high positions with insignificantly low costs. The adjustments make less of a difference for Germany right now due to low interest rate levels (likely due to massive QE), but it is visible that Italy is somewhat shielded in times of higher nominal rates as 25% of it is returned as dividends.

Furthermore, one could add other “dividends” such as interest paid on deposits (due to the negative deposit rate from the ECB), which could further brighten this calculation. In the US, interest paid on excess reserves (currently 10 bps) worsens the adjusted interest to GDP ratio.

Chart 5: Interest rate payments adjusted for the share held by Banca d’Italia and the Bundesbank

Will the cost be too high?

The purchasing amount and pace of central banks mixed with increasing inflation expectations could be a toxic cocktail. So which repercussions should markets expect? Inflation has already taken off and will likely stick around for at least the medium-term, which makes the case for higher long bond yields decent on both sides of the pond.

We don’t consider moderately higher long bond yields an issue for debt sustainability, since the Governments are decently shielded from such a move due to the large ownership from central banks. The only “pain-threshold” for government bond ownership for central banks would be sustainably high inflation and in such case it is not the worst case to be a large debtor.

Under the assumptions of growth rates in GDP and general government gross debt as projected by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and that the central bank holds a constant share of the public debt at the same level as of today, one-third in the US scenario, the case of higher yields and higher debt need not be a bad bishop.

Letting the central bank take over a larger share of public debt could be Alekhine’s gun if governments and central bankers line up and attack the single target of public debt. Thus, official debt cancellation may not even be needed as we are already living in a de facto debt annulment era, unless e.g. the ECB and the Fed manages to bring down the ownership percentage in government bond markets over time.

We don’t find such a scenario feasible and rather expect bond ownership from central banks to remain at least at current levels in the years ahead, why we are likely already living in some sort of de facto debt annulment era, even if no-one is publicly willing to admit to it.