Uddrag fra Authers:

The US regional bank crisis

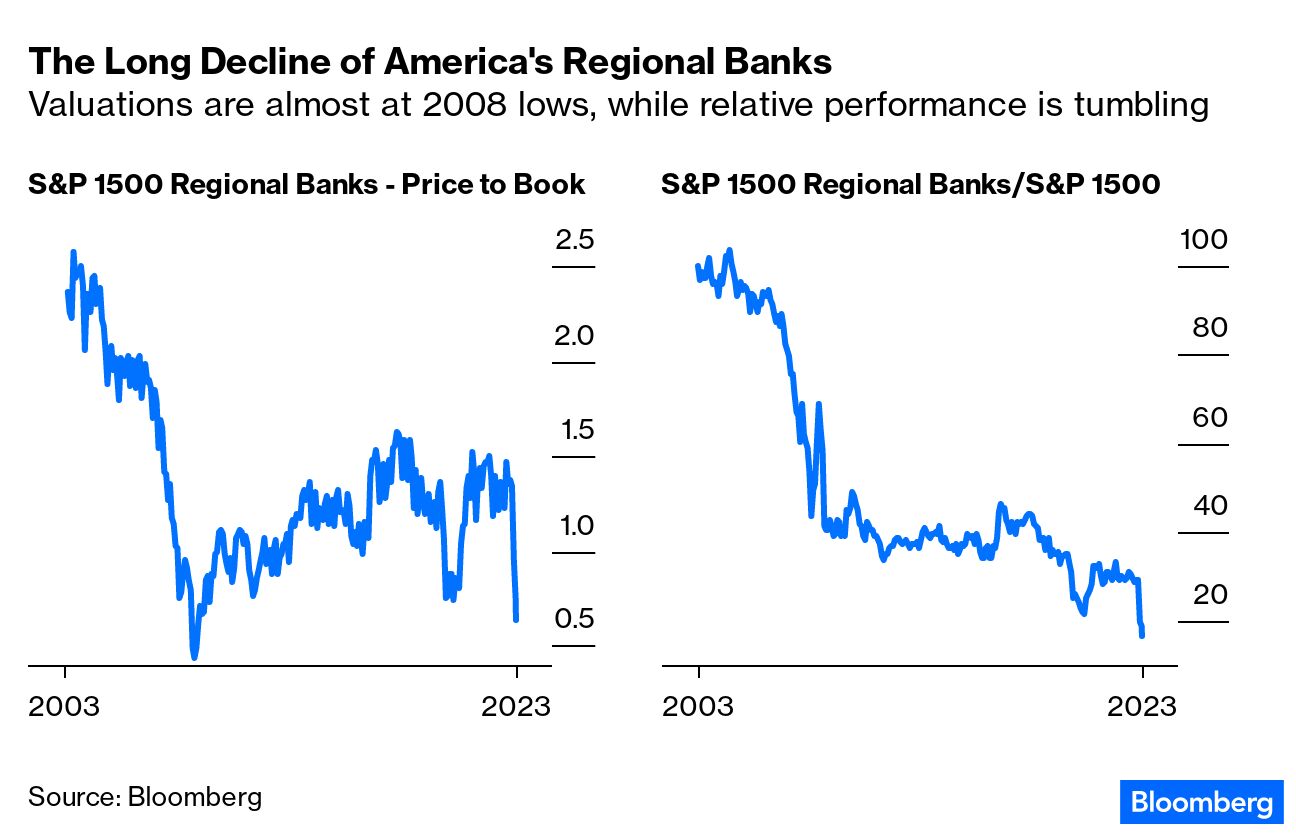

Despite the fire sale of First Republic over the weekend, confidence in regional banks grows ever weaker, with yet more selling of their shares Thursday. This is now getting to an extreme. Their valuation is almost back to the slough of despond in the Global Financial Crisis, while their relative performance compared to the market as a whole has plumbed a new depth:

This is not just affecting the smaller lenders, but has also taken big bites out of the market cap of some of the largest banking groups that lie outside the special regulatory category of those deemed too big to fail. The renewed speculation against one name after another is reminiscent of 2008. It’s dangerous to view everything through the lens of 2008, because it’s possible for a crisis to do serious damage while taking a different form, and not being quite as severe, as the GFC. That said, the temptation is strong as the GFC was the pivotal professional experience for most of the people now working in finance.

This is not like the GFC in the sense that it doesn’t hinge on distrust in the valuations of assets on banks’ books. It isn’t that investors fear that many of their loans are toxic. Rather, the issue now concerns profits. With interest rates where they are, the logic is that banks can only hold on to their deposits, a vital source of cheap funding, by offering rates to customers that obliterate their profits. This doesn’t directly threaten a bank, in the way that the bad loans did in 2008. But if a bank looks less likely to make profits, that will mean a lower share price, which in turn will make it harder for it to raise equity funding, and not just debt finance. Allowing consolidation in the banking sector would be painful for regulators, and for consumers who would likely get worse service and value for money from monopolistic monoliths. But it’s getting harder to resist.

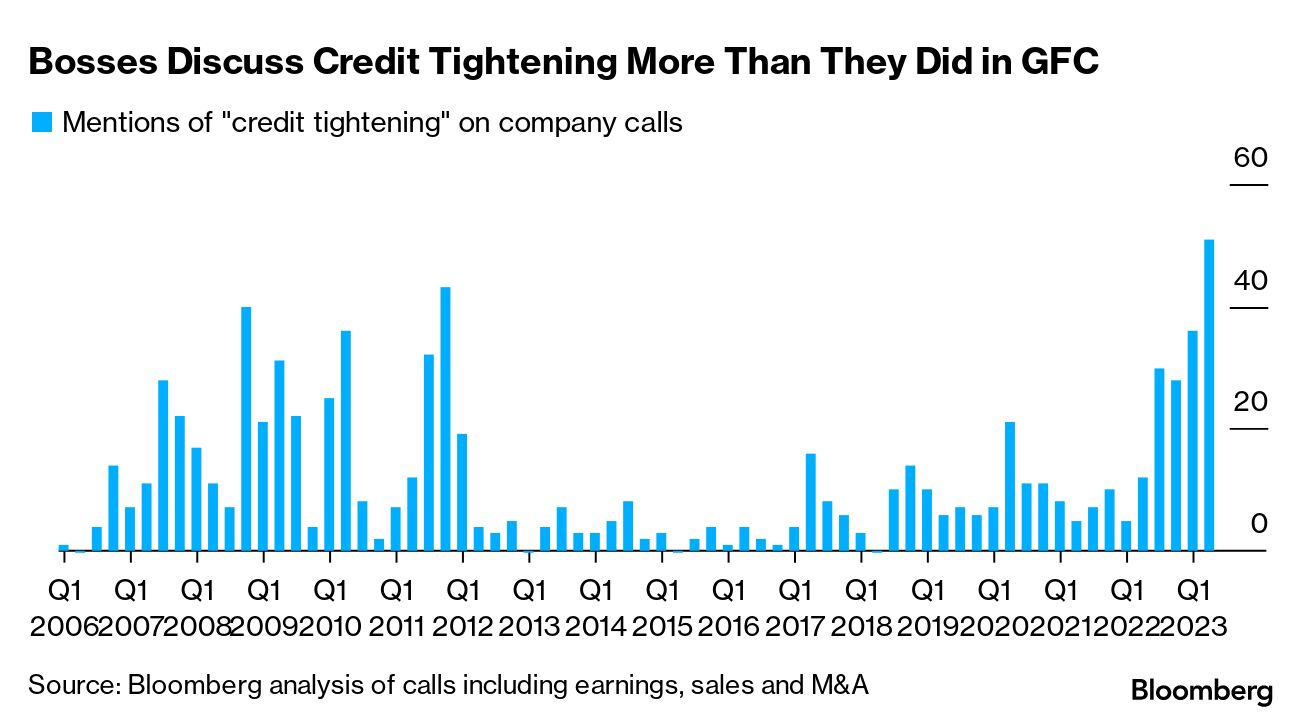

Why does it matter? First, banks that are in trouble will tighten credit, and companies are now very worried that this is happening and could worsen. Remarkably, Bloomberg colleagues show that credit tightening has come up more often in earnings calls over the last few weeks even than during the horrors of 2008:

Second, it could force changes in both monetary and fiscal policy. Yields have fallen again this week on the belief that the bank crisis will compel the Fed to ease monetary policy. Possibly even more important, the most obvious solution could involve a big fiscal outlay. Insuring all deposits, advocated by many as the measure that could end the crisis, would be mighty costly, even on an interim basis. To do it on a permanent basis would require legislation, which in turn would require America’s polarized politicians to agree on something.

This is very different in concept from what happened in 2008. And as the problem is one of liquidity, or banks’ ability to raise money in a hurry, rather than solvency, it should be far less serious. Bank crises do happen from time to time. That doesn’t mean that this crisis can be ignored, or that it won’t be painful.

Everything Else |

Markets are convinced that the Fed will pivot, and soon

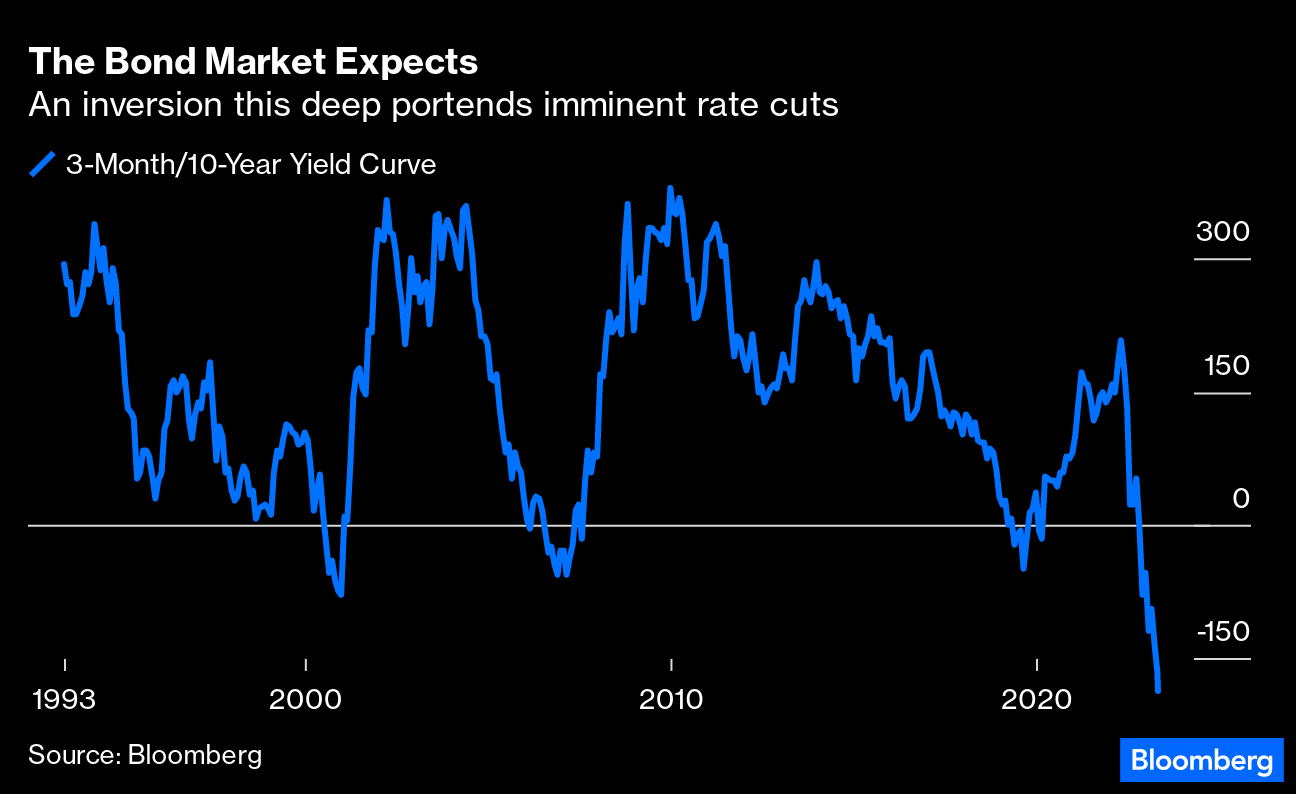

There are lots of ways to show this. For now, look at the gap between the three-month and the 10-year yields, generally regarded as a surefire recession indicator. It’s also a great indicator of imminent rate cuts. An inversion is also a timing signal, because it makes little or no sense unless you’re confident that rate cuts will be starting soon. And over the last 30 years, the curve has never been as inverted as it is now:

High numbers for employment payrolls or US inflation in the next few days could do some damage to this assumption. For the time being, belief in a pivot carries all before it once again.

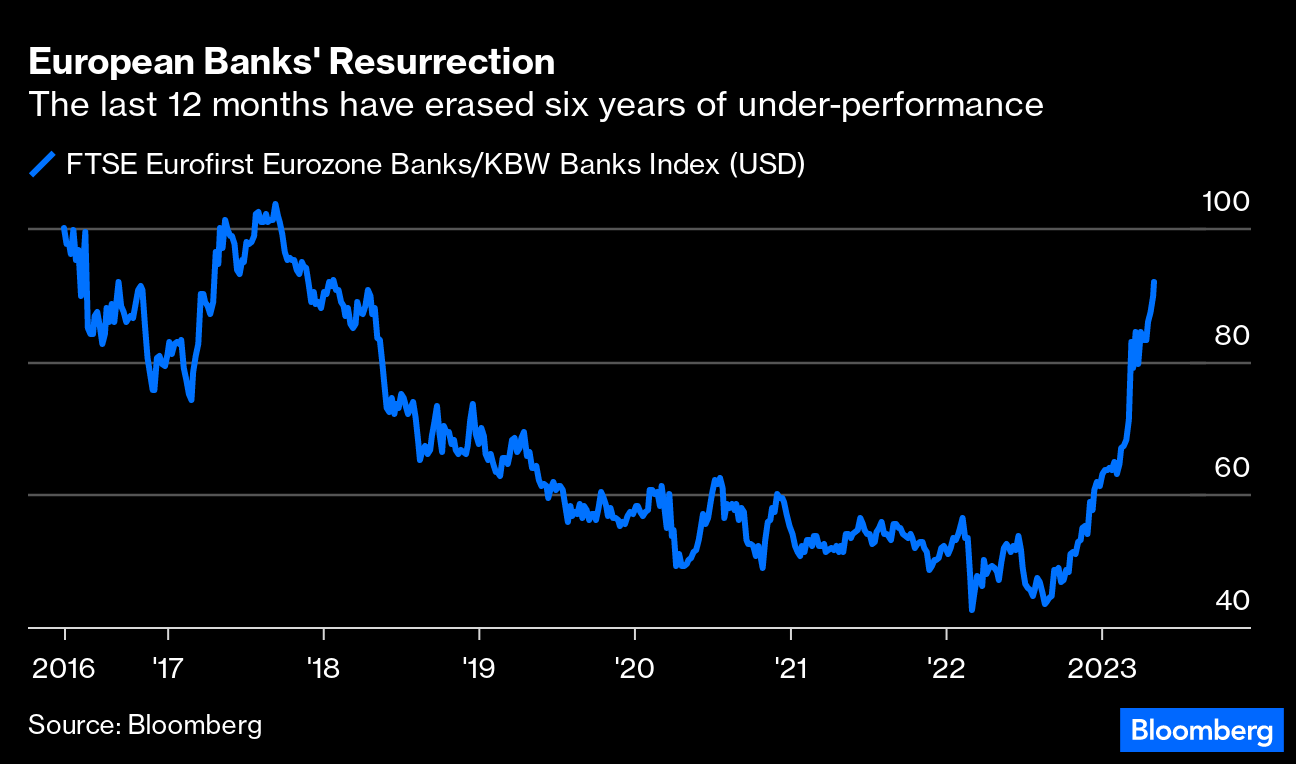

Europe’s banks haven’t been sucked in

Despite the shocking implosion of Credit Suisse Group AG only a few weeks ago, confidence in European banks is far greater than in their US counterparts. Perhaps because the European system is already buttressed with tighter regulations, and is far more concentrated, the stock market’s recent performance suggests a remarkable change in opinion. This is how two of the most closely watched indexes of large banks in the US and the euro zone have performed since the Brexit referendum in 2016 (which was treated as terrible news for Europe). The market seems to think the US regional bank crisis is a shock to rank with the departure of the UK from the EU: